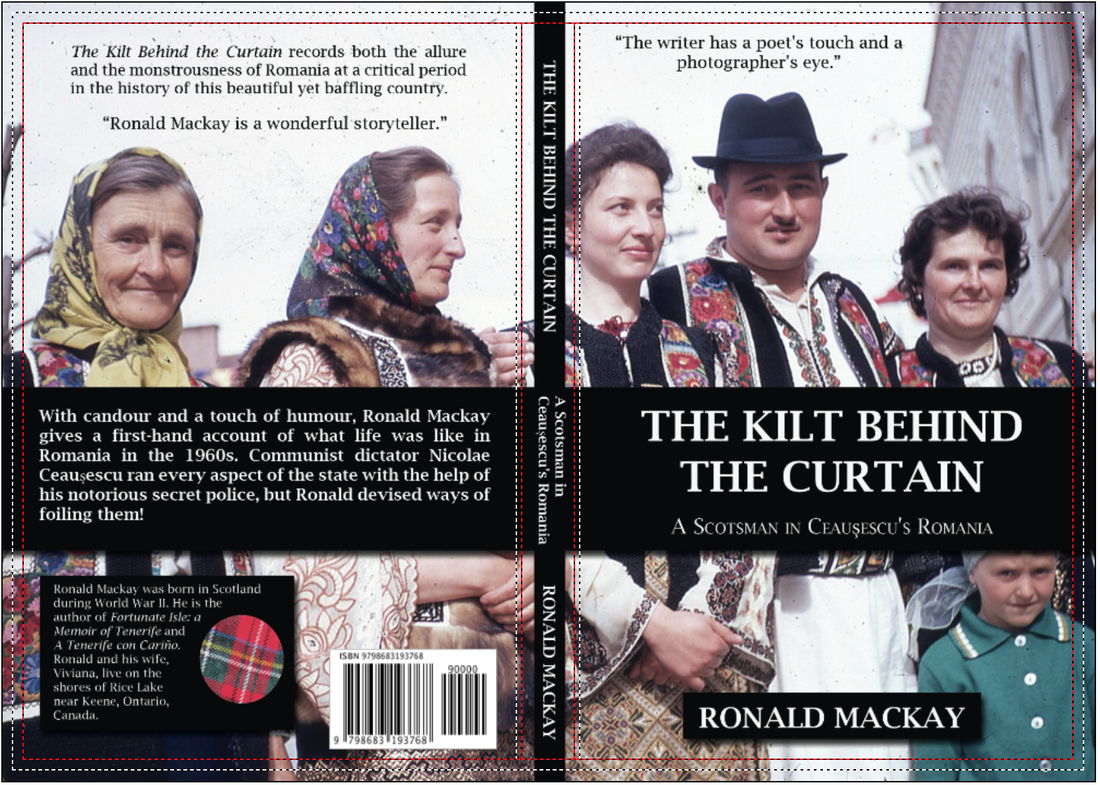

It is an honour to feature Ronald Mackay as our latest guest blogger, He talks about his new book, The Kilt behind the Curtain: A Scotsman in Ceaușescu’s Romania, which is released today, and gives us some background to his time in Romania.

Experiences Behind the Iron Curtain: Life in Ceaușescu’s Romania

“You, Mr Mackay, are the sharp end of the trade agreement that we are negotiating with the Romanians.” This is what the British Foreign office told Ronald in May 1967 just before he left for Romania as a visiting professor to Bucharest University.

The Kilt behind the Curtain: A Scotsman in Ceaușescu’s Romania tells of Ronald’s experiences during the two years he spent behind the Iron Curtain when he was in his mid-20s.

Here is what he has to say about his experiences that were often delightful, occasionally frightening, but never boring.

***

“When I began to write ‘The Kilt Behind the Curtain’,” Ronald says, “memories were unleashed. With surprising ease, I was able to remember people, names, places, events and even conversations. I could visualize how Romania was -- beautiful mountains and valleys, fairytale medieval towns, the faded elegance of its capital, Bucharest.

The Foreign Office official who briefed me before my departure warned me that Romania actively discouraged its citizens from associating with foreigners, especially from the West. Any Romanian who encountered a Westerner had to report the conversation to their Communist Party ‘base’. That meant a permanent record on their personal security file. To avoid such danger, the average Romanian, even my colleagues and students at the University, avoided informal contact with me.

***

I’d been selected by the British Government for this ‘hardship post’ because of my earlier experiences. In 1960, as the only foreigner working in the isolated banana plantations of north Tenerife, I’d learned self-sufficiency, the art of survival and the skill of fitting into a foreign culture. I’d also trained with the 3rd Battalion Gordon Highlanders and so I knew how to handle adversity.

In the mid-60s, the satellite countries around the USSR were little known in Britain. I knew that Romania was ruled by a single power, the Romanian Communist Party, that it had oilfields and much-valued agricultural land, and that the Carpathian Mountains formed its spine; that Romania had been absorbed into the Roman Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and later, into the Ottoman Empire.

***

My main concern when I first arrived was that I neither wittingly nor unwittingly cause a Romanian to get into trouble with the Communist Party. So, I was careful not to take the initiative in any personal encounter. I had to assume those willing to befriend me, or even to talk to me, had been cleared by the Party and probably enlisted as informers for the Securitate, Ceaușescu’s dreaded Secret Police. Because such circumstances isolated me, I spent a lot of time hiking alone in the Carpathians. If fellow-walkers talked to me in the mountain hostels I would respond warmly, but they tended to stick to their own small groups. Later, when I learned to speak Romanian, I could just about pass for a member of the Hungarian, Saxon, Bulgar or Turkish minority and so the stigma associated with being from the ‘West’ was reduced.

***

In my second year. I decided that the network of Securitate informants was too complicated for a foreigner like me to figure out, so I let individual Romanians decide for themselves, if and to what extent they wanted to associate with me. They knew what they were doing. I reacted openly to whoever came along. They were either taking a calculated risk or were police informants. Either way, I left the initiative and the responsibility to them.

The only Westerners in Romania at the time were diplomats who staffed the European and US embassies. There was the occasional British businessman. Feelers were being put out to explore trade opportunities. I made a small number of friends among these businessmen, but they visited irregularly and some, I suspect, were spies. I tell of one such case in the book.

From one businessman, I bought a broken-down Land Rover. The day I fixed it up, I took it for a test drive to Otopeni airport and back. There were few private cars in Romania at that time. I did notice, however, throngs of people waving flags as I returned to the city. Was it my mechanical genius that was being fêted? Unlikely! So I concluded there had been counter-revolution. The dictator Ceaușescu had been toppled. But no! The Militia stopped me and ordered me off the boulevard just second before a great car came into view. Charles de Gaulle was waving to the crowds! It was the 14th of May 1968 and the first visit of a Western Leader to Communist Romania.

I almost rained on the great General de Gaulle’s parade!

***

During my two years in Romania, I was so enamoured by the elegance of Bucharest’s architecture and the beauty of the countryside that I missed little of home.

Of course, life in these days of communist totalitarianism was difficult, but for me it was full of intrigue. I was young and fearless. I respected my fellow university professors as outstanding scholars and admired my students for their industriousness and attention to detail. I enjoyed the few friends that I made and didn’t much care whether they were secret police informers or not. I truly enjoyed being in Romania with all the opportunities it gave me to explore and experience a world that most of us in the West had never imagined.

***

The big difference between the UK and Romania was the absolute control that the Romanian Communist Party and its Secret Police exerted over the population. Everybody was ultra-careful not just with me but even with their fellow-citizens. One person did not trust another. Informers for the Securitate were everywhere.

***

I was fortunate to be able to visit most of Romania. The comfortable, ancient towns of Transylvania, the painted monasteries of Bukovina, and the great evergreen forests and mountains of Maramureș.

The city parks, Cişmigiu Gardens and Herăstrău Park were a delight. I liked to watch the older men play chess or swap postage stamps in Cişmigiu Gardens. I never tired of visiting the Muzeul Satului, the Village Museum, with its charming wooden buildings from every corner of Romania representing the county’s varied ethnic make-up.

Being a great walker, I explored the city on foot. However, I would often board a tram or a trolleybus and ride it to the terminus just to see new parts of the city or even to frustrate the Securitate agents whose job it was to tail me. I covered virtually every inch of that elegant city.

***

The most unexpected experience I had – many are recorded in the book -- was running into a group of camouflaged tanks in battle formation near the Soviet border in the north. I should not have been there, but I was showing off to a friend visiting from the UK, and I wanted to get us as close to the border so we could to peek into the Ukraine. As an infantryman in the Gordon Highlanders, I had accompanied tanks on operations, so I knew exactly what I was seeing. That’s the only time in two years that I thought faster than a Romanian. I talked my way out of the crisis without harming the two Romanian women who were accompanying us. The full story is told in the book.

***

Now, after 50 years, what I still miss about Romanians is their spontaneity. Everywhere else I’ve lived, almost every hour of every day is scheduled; there’s little room for the impromptu. Romanians, at that time, thrived on the unexpected.

***

The Kilt behind the Curtain: A Scotsman in Ceaușescu’s Romania is available from any bookstore and as a paperback and eBook from Amazon.

***

As a boy in Scotland in the ‘50s, Ronald Mackay worked on farms and in forests, and hitchhiked from Dundee to Morocco and back when he was 17. After leaving the Morgan Academy in 1960, he worked in banana plantations on Tenerife in the Canary Islands. To cover expenses at Aberdeen University, he graded skins for the Hudson’s Bay Company in London, fished cod off the Buchan coast, and drove a mammoth dump-truck in the tunnel excavation of Ben Cruachan in Argyle, to create the first pumped-storage hydroelectric power station in Scotland.

Behind the Iron Curtain from ‘67 to ‘69 he was Britain’s visiting professor at Bucharest University and later travelled throughout Eastern Europe. From a post in Mexico, D.F in the ’70s, he explored Mexico and Guatemala. While teaching project design, management, and evaluation at Concordia University, Montreal, he worked from Newfoundland to Vancouver Island as well as all over Canada’s Arctic; held posts in Toronto, Edinburgh, and Singapore; and ran a working farm in Ontario.

Later, as a development project specialist, he helped improve the application of agricultural research technologies in Bangladesh, India, the Philippines, Tanzania, the Middle East, and throughout Latin America while developing a vineyard in Argentina with his Peruvian wife, Viviana. Ronald credits Viviana as his muse.

Since 2012, Viviana and he have lived near Keene on Rice Lake, Ontario.

He writes plays and short stories and has published three previous memoirs: A Scotsman Abroad: A Book of Memoirs 1967-1969; Fortunate Isle, A Memoir of Tenerife; and in Spanish, A Tenerife con Cariño.

Ronald’s Amazon Page: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Ronald-Mackay/e/B001JXCBL8

Link to The Kilt behind the Curtain: A Scotsman in Ceaușescu’s Romania

“You, Mr Mackay, are the sharp end of the trade agreement that we are negotiating with the Romanians.” This is what the British Foreign office told Ronald in May 1967 just before he left for Romania as a visiting professor to Bucharest University.

The Kilt behind the Curtain: A Scotsman in Ceaușescu’s Romania tells of Ronald’s experiences during the two years he spent behind the Iron Curtain when he was in his mid-20s.

Here is what he has to say about his experiences that were often delightful, occasionally frightening, but never boring.

***

“When I began to write ‘The Kilt Behind the Curtain’,” Ronald says, “memories were unleashed. With surprising ease, I was able to remember people, names, places, events and even conversations. I could visualize how Romania was -- beautiful mountains and valleys, fairytale medieval towns, the faded elegance of its capital, Bucharest.

The Foreign Office official who briefed me before my departure warned me that Romania actively discouraged its citizens from associating with foreigners, especially from the West. Any Romanian who encountered a Westerner had to report the conversation to their Communist Party ‘base’. That meant a permanent record on their personal security file. To avoid such danger, the average Romanian, even my colleagues and students at the University, avoided informal contact with me.

***

I’d been selected by the British Government for this ‘hardship post’ because of my earlier experiences. In 1960, as the only foreigner working in the isolated banana plantations of north Tenerife, I’d learned self-sufficiency, the art of survival and the skill of fitting into a foreign culture. I’d also trained with the 3rd Battalion Gordon Highlanders and so I knew how to handle adversity.

In the mid-60s, the satellite countries around the USSR were little known in Britain. I knew that Romania was ruled by a single power, the Romanian Communist Party, that it had oilfields and much-valued agricultural land, and that the Carpathian Mountains formed its spine; that Romania had been absorbed into the Roman Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and later, into the Ottoman Empire.

***

My main concern when I first arrived was that I neither wittingly nor unwittingly cause a Romanian to get into trouble with the Communist Party. So, I was careful not to take the initiative in any personal encounter. I had to assume those willing to befriend me, or even to talk to me, had been cleared by the Party and probably enlisted as informers for the Securitate, Ceaușescu’s dreaded Secret Police. Because such circumstances isolated me, I spent a lot of time hiking alone in the Carpathians. If fellow-walkers talked to me in the mountain hostels I would respond warmly, but they tended to stick to their own small groups. Later, when I learned to speak Romanian, I could just about pass for a member of the Hungarian, Saxon, Bulgar or Turkish minority and so the stigma associated with being from the ‘West’ was reduced.

***

In my second year. I decided that the network of Securitate informants was too complicated for a foreigner like me to figure out, so I let individual Romanians decide for themselves, if and to what extent they wanted to associate with me. They knew what they were doing. I reacted openly to whoever came along. They were either taking a calculated risk or were police informants. Either way, I left the initiative and the responsibility to them.

The only Westerners in Romania at the time were diplomats who staffed the European and US embassies. There was the occasional British businessman. Feelers were being put out to explore trade opportunities. I made a small number of friends among these businessmen, but they visited irregularly and some, I suspect, were spies. I tell of one such case in the book.

From one businessman, I bought a broken-down Land Rover. The day I fixed it up, I took it for a test drive to Otopeni airport and back. There were few private cars in Romania at that time. I did notice, however, throngs of people waving flags as I returned to the city. Was it my mechanical genius that was being fêted? Unlikely! So I concluded there had been counter-revolution. The dictator Ceaușescu had been toppled. But no! The Militia stopped me and ordered me off the boulevard just second before a great car came into view. Charles de Gaulle was waving to the crowds! It was the 14th of May 1968 and the first visit of a Western Leader to Communist Romania.

I almost rained on the great General de Gaulle’s parade!

***

During my two years in Romania, I was so enamoured by the elegance of Bucharest’s architecture and the beauty of the countryside that I missed little of home.

Of course, life in these days of communist totalitarianism was difficult, but for me it was full of intrigue. I was young and fearless. I respected my fellow university professors as outstanding scholars and admired my students for their industriousness and attention to detail. I enjoyed the few friends that I made and didn’t much care whether they were secret police informers or not. I truly enjoyed being in Romania with all the opportunities it gave me to explore and experience a world that most of us in the West had never imagined.

***

The big difference between the UK and Romania was the absolute control that the Romanian Communist Party and its Secret Police exerted over the population. Everybody was ultra-careful not just with me but even with their fellow-citizens. One person did not trust another. Informers for the Securitate were everywhere.

***

I was fortunate to be able to visit most of Romania. The comfortable, ancient towns of Transylvania, the painted monasteries of Bukovina, and the great evergreen forests and mountains of Maramureș.

The city parks, Cişmigiu Gardens and Herăstrău Park were a delight. I liked to watch the older men play chess or swap postage stamps in Cişmigiu Gardens. I never tired of visiting the Muzeul Satului, the Village Museum, with its charming wooden buildings from every corner of Romania representing the county’s varied ethnic make-up.

Being a great walker, I explored the city on foot. However, I would often board a tram or a trolleybus and ride it to the terminus just to see new parts of the city or even to frustrate the Securitate agents whose job it was to tail me. I covered virtually every inch of that elegant city.

***

The most unexpected experience I had – many are recorded in the book -- was running into a group of camouflaged tanks in battle formation near the Soviet border in the north. I should not have been there, but I was showing off to a friend visiting from the UK, and I wanted to get us as close to the border so we could to peek into the Ukraine. As an infantryman in the Gordon Highlanders, I had accompanied tanks on operations, so I knew exactly what I was seeing. That’s the only time in two years that I thought faster than a Romanian. I talked my way out of the crisis without harming the two Romanian women who were accompanying us. The full story is told in the book.

***

Now, after 50 years, what I still miss about Romanians is their spontaneity. Everywhere else I’ve lived, almost every hour of every day is scheduled; there’s little room for the impromptu. Romanians, at that time, thrived on the unexpected.

***

The Kilt behind the Curtain: A Scotsman in Ceaușescu’s Romania is available from any bookstore and as a paperback and eBook from Amazon.

***

As a boy in Scotland in the ‘50s, Ronald Mackay worked on farms and in forests, and hitchhiked from Dundee to Morocco and back when he was 17. After leaving the Morgan Academy in 1960, he worked in banana plantations on Tenerife in the Canary Islands. To cover expenses at Aberdeen University, he graded skins for the Hudson’s Bay Company in London, fished cod off the Buchan coast, and drove a mammoth dump-truck in the tunnel excavation of Ben Cruachan in Argyle, to create the first pumped-storage hydroelectric power station in Scotland.

Behind the Iron Curtain from ‘67 to ‘69 he was Britain’s visiting professor at Bucharest University and later travelled throughout Eastern Europe. From a post in Mexico, D.F in the ’70s, he explored Mexico and Guatemala. While teaching project design, management, and evaluation at Concordia University, Montreal, he worked from Newfoundland to Vancouver Island as well as all over Canada’s Arctic; held posts in Toronto, Edinburgh, and Singapore; and ran a working farm in Ontario.

Later, as a development project specialist, he helped improve the application of agricultural research technologies in Bangladesh, India, the Philippines, Tanzania, the Middle East, and throughout Latin America while developing a vineyard in Argentina with his Peruvian wife, Viviana. Ronald credits Viviana as his muse.

Since 2012, Viviana and he have lived near Keene on Rice Lake, Ontario.

He writes plays and short stories and has published three previous memoirs: A Scotsman Abroad: A Book of Memoirs 1967-1969; Fortunate Isle, A Memoir of Tenerife; and in Spanish, A Tenerife con Cariño.

Ronald’s Amazon Page: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Ronald-Mackay/e/B001JXCBL8

Link to The Kilt behind the Curtain: A Scotsman in Ceaușescu’s Romania