New Year’s Eve, 2019. Part 1. By Mike Cavanagh

The house phone rang just after 6 a.m. on New Year’s Eve and my wife Julie got out of bed to answer it. In a doze I could just hear her say,

“Hello?”

Then nothing further. As she came back, she said,

“It was a recorded message from the Rural Fire Service. The fire’s crossed the highway and heading our way. We should be prepared to leave.”

Strange thing, we’d been expecting this call, yet when it arrived it just didn’t seem real. Julie came back to bed and booted up her laptop to check the online fire information. I got up to make the coffee; something real at least.

* * *

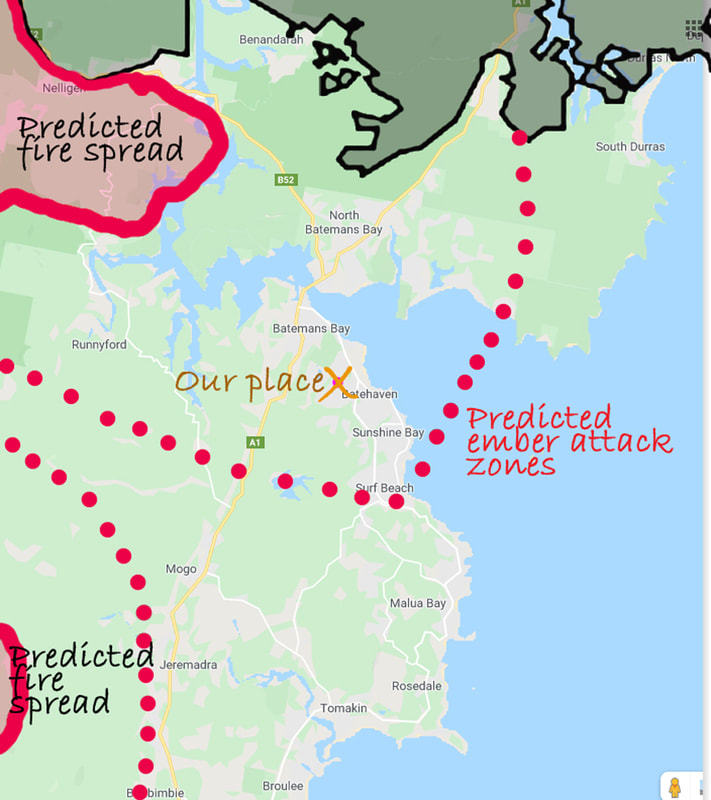

From as early as the beginning of August 2019, a month before Spring, it was clear that unless the heavens opened in a prolonged drenching, this fire season would be one of the worst on record. Sadly, the heavens remained closed for business, and by early September south-east Queensland and north-east New South Wales were littered with fires; some small, some big, but all growing. By October, a fire had sprung up between Canberra and Braidwood, some 60 kilometres north west of where we live, and a number of fires in the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney. Then in early November, a fire began in the State Forest near a place called Currowan, some 25 kilometres north west of us. As the fire front bore down towards the coast some ten kilometres north of us, it was clear as November headed towards December that the coastal townships in its path where in dire straights. We knew and loved these places; Depot Beach, Durras North, South Durras, Pretty Beach, Kioloa. Our adult son, Dan, who lives with us, had some friends with properties up there. Crowded places in summer and school holidays, but otherwise peaceful and leafy retreats for the residents, local day trippers (us) and surfers (Dan). Those who lived there looked like they might pay a heavy price now for the beautiful coastal bush that surrounded them.

Where we live, in Catalina, a suburb of Batemans Bay (population 17,000 odd), we’d been experiencing the distant reach of the fire for some weeks already as ‘smoke haze likely’ became part of our daily weather forecast. We rarely saw stars at night, washing was hung to dry inside on the bad days and working in the garden restricted to the better days, usually when a nor’ easter blew in from the sea. As rare event as it was a welcome one. On the days when the wind was from the north west, fine grey ash flakes floated down, their gentle rocking as they drifted along belying the fury behind their origin.

Checking the RFS fire mapping was now a daily routine for me, and often several times a day as things were moving so quickly. Julie kept daily tabs on her laptop on what was happening via the local news and media websites, and Dan often came in to sit with me while we perused the online fire maps, trying to figure out what the likely scenarios were.

Somehow, no, not somehow, but through the amazing efforts of the RFS and National Parks and State Forests fire crews, the coastal townships and properties were in the main saved as the fire swept down to the coast. In the end only stopped by running out of things to burn, scorching all right down to the water’s edge. In particular, the efforts of the RFS crews were epic and it would be a disservice to call their efforts ‘tireless’ as they battled well beyond fatigue, well beyond being tired, exhausted, choked on smoke, smeared in ash, and sweltering within their life saving but bloody hot and heavy suits and helmets.

By the 3rd of December the fire had stopped at the sea, and the coastal townships in the main saved, we felt like we might have ‘dodged a bullet’. Yet we knew the fire season had barely begun and the long-term weather reports could only suggest the chance of any significant rain by late February or early March. The highway north remained closed as fire crews continued to mop up and still smouldering trees were brought down along the road.

But while the fire front had stopped at the coast, its north and south flanks continued to spread slowly. The southern flank soon reached the Kings Highway (which headed west to Canberra) about 14 kilometres away, and we were cut off now both north and west. The road south remained open, but that wouldn’t last for long.

We were in a cycle of weather that seemed to have been locked in for months now; hot dry nor’ westers for three or four days, then a rapid swing around to a brief, blustery southerly, before perhaps one day of respite with north easterlies. Then the nor’ westers swept down again, and each time the fire took off with a vengeance. It had already burned through over 50,000 hectares and along it’s northern front, some 90 kilometres away, it was now threatening the towns and villages further north along the coast. And it wasn’t the only fire burning along the eastern ranges, not by a long shot.

By mid-December it felt like the whole east coast was ablaze and we watched the nightly news with growing awe and anxiety. We were barely into the fire season and already lives and many homes had been lost. From the size of the areas now burning it was inconceivable that there could be enough fire fighters to even begin to countenance saving every threatened property. It was equally inconceivable how the women and men of the RFS were still standing, let alone able to drag their sleep-deprived, energy sapped bodies into another battle. In the face of such conflagrations there was no way these fires could be stopped. All that those on the front line could do was turn up at the next life or property threatened, do the best they could, then head off without respite to the next crises situation. I can’t help but shake my head even now thinking about it. Bloody marvels, each and every one of them.

For more than a week beforehand, the RFS and Bureau of Meteorology had been issuing warnings about predicted ‘catastrophic’ conditions predicted for 31st December. Temperatures were due to soar well into the 40s (approx. 105F) with hot dry westerlies for the day before and leading into New Years Eve, with a southerly change predicted to head up the coast from mid-morning. From my training and experience fighting fires as a ranger, the words ‘wind shift’ in the context of wild fires still make my stomach twist in a knot; flight or fight response kicking in I guess. The problem with wind shifts is that they turn what were more slowly and less fiercely burning fire flanks into far hotter, speedier and much more dangerous fire fronts. The time you thought you had to get yourself out shrinks from a half-hour to a handful of minutes, and from minutes to mere seconds, if you can make it out at all. It can catch even the most well trained and well prepared.

In preparation for the 31st, Julie, Dan and I began a regime of hosing down the house and the surrounding garden and garden trees. We love our place, but it’s a 1970’s expanded beach cottage with wood-fibre Hardy-plank walling and a large timber framed and decked front verandah. We’ve got a small bush reserve behind us and a number of shrubs and trees overhang the fence. A lot of ground ‘litter’, dead, dry plant matter, had built up on the other side of our old timber fence. I cleared and cut away what I could but could do nothing about my greatest concern, a twelve metre high, crusty old dying black wattle that leaned towards our yard, its main upper branches arching high and well over the fence.

We hooked up two of the garden hoses together so I could hop over the fence and water into the reserve for up to 10 metres, and I paid mind to wet the trees as best I could. Water was precious in the ongoing drought, but not compared to our home and lives. The wetting down wouldn’t stop a fire if it started up in the reserve, but it might slow it down enough, if it came to it, to give us time to save the house, or ourselves, if needs be.

On the evening of 30th December, reports had come through that the township of Mogo, about nine kilometres south-west of us along the Princes Highway, had been evacuated as the fire raged towards it. A spur of the main fire further to the west had jumped containment lines and curled down south through the bush to the west of the highway, and when the daily nor’wester blew, it changed course and headed east and straight for Mogo. Wind shifts. Can be a yachter’s blessing and a fire-fighters curse.

Dan and I sat at the computer that night of the 30th and pulled up the Rural Fire Service fire mapping, and as the outline of the fire appeared, Dan pointed at the screen.

“What’s that about?”

On the map the main front of this southern extension of the fire was at Mogo, and it didn’t look good at all for the township. But this wasn’t what he was pointing at. Fire mappers try to match the onscreen mapping as accurately as possible so that anyone viewing the information has the best possible idea of where the fire edges are. But what we were looking at was a bold, elongated, black rectangle extending north of Mogo straight out for two kilometres to the east.

“Looks like the fire has obviously jumped the highway,” I replied, “and I’d say it’s travelling too rapidly for the mappers to accurately map. If that’s the direction it heads tomorrow, we might be in trouble, depending on when the southerly kicks in.”

“That’s not good.”

“No,” seemed to cover it.

We went to bed on the 30th wondering what the next day would bring. One thing we knew it would bring was a southerly wind change, sometime in the morning. If the fire was south of us when it hit…

We were cut off by road, soon to be surrounded by fire. No, whatever tomorrow would bring, it wasn’t going to be good.

The phone call the next morning on New Year’s Eve would confirm that.

Smoke haze from fires, 29th December

Predicted fire spread for 31st December

TO BE CONCLUDED IN PART 2