“Made by My Father Out of Polish Steel” by Patsy Hirst

“Soocha”.....”Sooooocha”. We sang her name as we passed under her bedroom window on the way to the front door. This way she could get started on what, for her frail legs, was a tortuous journey down four steps and across the living room to greet us.

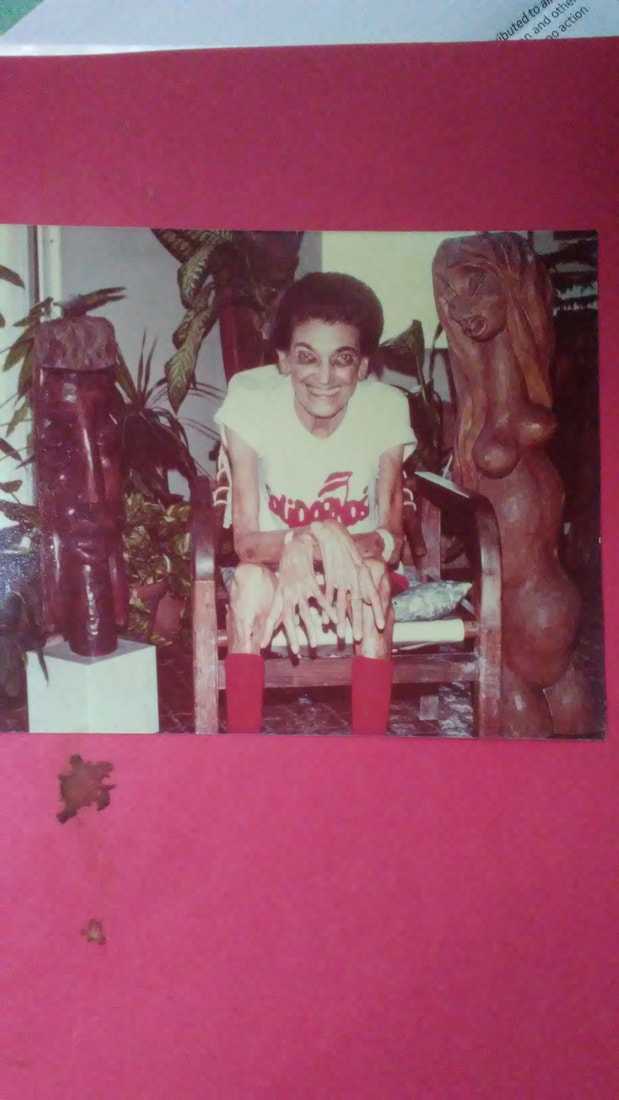

“Hello! Oh, thank you! You’re the only ones who ever hug me!” The meager 68 pounds that stretched over her 5’7” frame was deceptive. Surprisingly strong arms returned our hugs, arms muscled from years sculpting the hard woods found on this island she called home.

She’d dubbed us “my three angels”, my two teen-age daughters and me, and was delighted one Christmas when we gave her a tiny wind chime with three dangling cherubs. But sometimes we didn’t feel too saintly as we trudged the dark, pot-holed road and climbed the steep drive to her house. It was often begrudgingly that we left homework and dirty dishes for such visits. And the first twenty minutes or so usually didn’t offer much encouragement to stay. There was the list of the day’s physical complaints, followed by the problems of trying to coordinate friends and taxis for shopping and doctor appointments. But then came the good part.

After venting these normal frustrations of isolation and loneliness, the storytelling began. Never did we leave Socha’s house without feelings of exhilaration, inspiration, and awe, as well as gratitude that our lives were blessed with such a friend.

Socha’s life unfolded before us, through her vivid memories and animated descriptions. A synopsis would sound like the back cover of any number of popular novels: “A saga of love and turbulence, spanning the continents...of one talented European woman and the two men who shared her heart... “. The difference is that this wasn’t fiction. It was true, and we were hearing it firsthand.

Socha’s mother was French, but it was her Polish father and ancestry that she identified with, and to her Polish nanny, Stastia, that she remained close to throughout her life. “I’m made by my father out of Polish Steel”, Socha liked to quip, and proved it true many times. Her childhood consisted of city and country houses in Poland and Berlin; a well-dressed mother always dashing off to social functions, and a father wavering between reality and his own fantasies; a preference for animals over siblings; frequent stays in hospitals due to a bronchial illness; and, always, her drawing.

“A huge umbrella blocking the corner of the kitchen was my first ‘studio’ when I was three years old. When I was six, I proudly presented my beloved father with a picture, but he ripped it in two and flew into a tirade about only sketching animals and flowers and only seeing the beauty of things.” There was no way this frightened, innocent child could fathom the fears that drove her father. There was no beauty in the approach of Hitler’s terror.

Socha’s art became her refuge. “The nuns at school were very strict” she remembers. “They would never praise my paintings, but they never returned them to me. Later I would see them hanging in the offices and hallways.” Her talent was honed in the Berlin atelier of Max Dungert, which was becoming a gathering place for subversive activists as well as artists. But Socha’s dedication kept her aloof from such rumblings; her exuberance for life itself protected her from any grimness that tried to encroach on her world. She was young, beautiful, talented, and happy, and only occasional stays at the Swiss TB sanitorium interrupted her otherwise blissful existence.

What more could she possibly want – except, of course, love. His name was Rainer Hildebrandt. He saw Soha for the first time on Berlin’s bustling Kurfurstendamn. He passed her, but was so taken by her beauty that he impulsively grabbed the back of her neck, turning her face to his. “I couldn’t help it” Rainer would tell me 40 years later, remembering as if it were yesterday. “I knew it was terribly brash, but I had to see that face. But, then, what could I do but apologize and mumble that I had mistaken her for someone else?”

“They were the most beautiful blue eyes I’d ever seen,” Socha would declare, when relating the same incident. “I couldn’t get them out of my mind, and kept wondering who he was and if I’d ever see him again.” One week later, quite by coincidence, Socha and Rainer were formally introduced by her best friend, Siga. It was not the beginning of this love story; it had already begun that day on the street. The passion of youth sped the romance along, but the imminence of war precluded planning for the future. Socha’s abundant zest and optimism balanced Rainer’s serious political and clandestine involvements, but the time came when they could no longer pretend. For Socha to survive, both physically and artistically, she must stay at the sanitorium in Davos, Switzerland. For Rainer to fulfill his anti-Hitler plots, he could not leave Berlin.

Monotonous days of sanitorium life were sometimes relieved by visiting and walking with fellow patient Michael Svender. “We had passed on the trails many times, but, of course, it was not proper to stop and speak, as we had not been formally introduced. But, one day, I glanced back over my shoulder, and Michael had also stopped and was looking back at me.” She gave a schoolgirl giggle as she remembered. “We became good friends.” A quiet, peaceful man, he surprised her by describing his underground dealings and aid to escaping Jews. It was through his connections that she was able to exchange occasional letters with Rainer. However, not only did the letters eventually stop, but so did the funds from Socha’s family. Their inability to send money out of Germany forced an end to her expensive stay at the sanitorium. She accepted Michael’s help in establishing a home in Davos, and later his proposal of marriage.

“It was a hard time for us,” Socha recalls. “There was seldom enough food, and we frequently had Jews staying with us till Michael could prepare their new papers. The doctors accepted my paintings as payment, and we often got medicines from a veterinarian friend.” But there were special times, too. Their love grew and matured, just as the tulip that Michael secretly nurtured to bloom in time for Socha’s April first birthday.

In the fall of 1946, the Svenders at last realized their dream of emigrating to America. Unable to get seats on the first KLM flight from Amsterdam to New York, it allowed them to have a few days for admiring the great museums and paintings of the city. It also allowed them to live; that first flight crashed, killing all aboard.

Fearful that her cough would prevent their entering the U.S., Socha slipped into the airplane bathroom just before landing, and injected herself with a medication provided by the vet. The needle bent; she used it anyway. “Must have struck a vein of Polish steel”, she laughs. Socha credits the English she learned watching American movies with helping them through the red tape on arrival. When an obstinate official picked out a minor wording in their papers, Socha burst into the lyrics of a popular musical: “You say TO-MA-TO, I say TO-MAH-TO....”. The immigration man softened, and they were admitted.

“I felt like an embryo as I went up in the Statue of Liberty,” recalls Socha of their first days in N.Y. “I was beginning a new life in America.” Their new life centered on finding jobs, Socha first as a governess, and then a commercial artist designing toys; Michael as an antique restorer, progressing to interior designer.

A small article in the N.Y. Times, Feb.14, 1949, was the first Socha had heard of Rainer since her early days in Switzerland. It described how he, through his “Fighting Group Against Humanity”, had documented the capture and slaying of hundreds of thousands by the Russians. She wrote Siga, who helped reestablish contact between these two extraordinary people. Through correspondence, Socha learned of his wartime experiences, twice captured and escaping the Nazis. He was even hidden for a time by her father, and was the only survivor of the five-man attempt to kill Hitler.

They even managed a brief reunion when Rainer visited N.Y. on business. Socha’s face clouded with nostalgia as she relived the scene. “Michael understood that I must go alone. We met at a café, just as on our first date. As soon as I saw him, I felt the same way I had so many years ago in Berlin.” She paused, trying to find the right words to express the emotions she experienced. “There are many different kinds of love,” she explained. “I loved Michael, we had a good marriage, and I would never have done anything to hurt him. But, if Rainer had said, ‘Come home with me’, it would have been very hard to say no.” Even though Rainer would marry twice and have three children, this very special friendship would continue throughout their lives.

Seeking a warmer climate, the Svenders took a trip through the southwest to California. “My favorite part was sunning on the back of our Pontiac convertible as Michael drove across the desert,” Socha said, stretching her lanky body out on the bed to demonstrate. “I loved not only the warmth of the sun, but the openness, the freedom. Switzerland was beautiful, but I always felt closed in by the Alps. I often painted palm trees and sunny beaches.” Just such a scene appeared on a brochure for the Virgin Islands Socha picked up in a California travel agency, and she eagerly read it that night. At 2:00 a.m. she awakened Michael. “This is where we’re going!” she declared, showing him a picture of St. Croix.

And, she was right. A planned one-month visit to the island stretched to three months, and convinced them of two things: this Caribbean paradise was where they wanted to live, and Socha’s art would enable them to do so. Paintings she did at the beach were often sold before she reached home, and the Tourism office often sent island visitors in search of local art work to her door.

It was after their move to St. Croix that the Svenders’ complementary talents were fully recognized. They opened a shop for ‘fine art and antiques’ called The Little Guardhouse. “What a job it was getting it ready,” she shuddered. “The building was a former Danish bootery, then was used as a motorcycle repair shop. It took 103 gallons of white paint to cover the walls.” Michael’s business ability and discriminating choice of antiques and historic art provided Socha the freedom to paint. Their joint efforts created a unique spot that was featured in many magazines and Caribbean guide books.

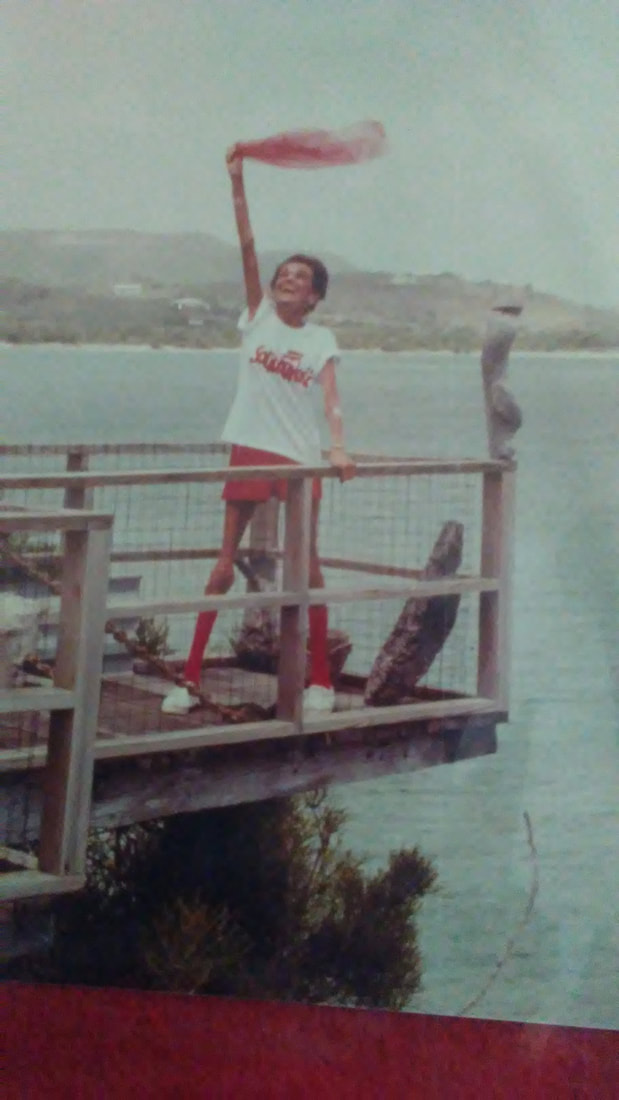

Socha enjoyed exploring her new island home with its bounty of natural beauty, and it was on one of these frequent jaunts that she spied a huge pillar on the beach in Frederiksted. It had recently been removed from the pier, and Socha declared indignantly, “They were going to burn it!” The potential she envisioned in that old beam began a whole new artistic field for her. From that abandoned wood and others – fishermen's buoys, driftwood, ancient beams from sugar mills and plantation ruins – often dragged home with great difficulty - would emerge a family of 128 sculptures. They would eventually be scattered as far away as California and Sweden, and recognized with exhibits in New York and Puerto Rico. But, to Socha, the greatest honor came from a young native girl. “She called me, ‘The Lady Who Makes People Out of Trees’. It was the best compliment I ever got” Socha remembered with pride.

Though both were plagued with poor health, Socha and Michael seemed able to always muster the strength and support to care for each other. Excerpts from her diaries revealed difficulties Socha encountered but never complained about. (“Michael fell again, but I was able to get him back up without calling the neighbors.”) It became even harder in their later years, and eventually Socha had to close the shop and devote herself entirely to Michael’s care, holding his hand one full-moon night until it became cold. Only then would she summon neighbors and allow her exhausted body to rest.

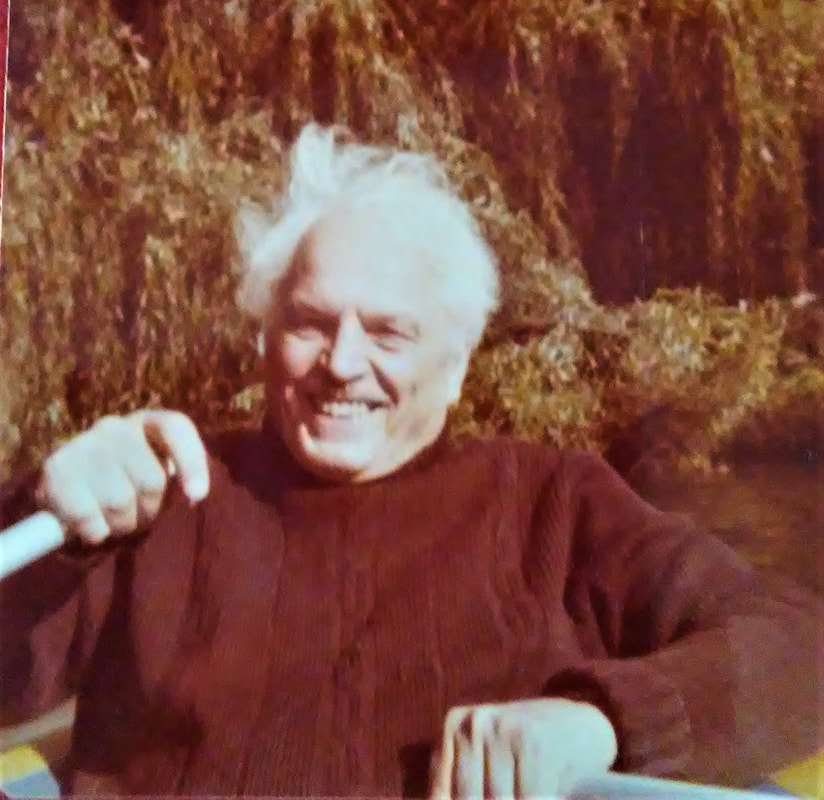

The one thing that rallied Socha in these miserable days was a phone call from Rainer in Berlin. She had left a message for him of Michael’s death, and was restored by his strong voice and assurance of help. It was over a year before Rainer was able to fulfill his wish of coming to see the love of his youth. It was only a one-night visit; a visit that dropped years from both their appearances. “A lion of a man” Socha had labeled him, and his shock of white hair and powerful presence proved it an apt description.

“I’ll sleep right there”, Rainer emphatically declared, his outstretched arm pointing to the other half of Socha’s king size bed. The busy-body neighbor who had offered her guest room timidly retreated. But there wasn’t much time for sleeping. The night was spent catching up on their pasts; the next morning a quick introduction to the island on the way to the airport.

A huge, “Whew!” was about all Socha could manage after Rainer’s whirlwind visit. But the love and pride shone in her eyes. “He liked my work! He wants to make a book about it.” Socha could hardly contain her joy and enthusiasm at the prospect. “I always told the magazine people, ‘Don’t write about me, write about my art. I want to be remembered as an artist.’ Now, I will be.”

A few months later, Rainer returned to St. Croix. His intensive pace was exhausting to Socha, but it was a labor of love. For days he took notes by hand as she described each member of her ‘wooden family,’ easily recalling the type of wood, where she acquired it, who purchased it, etc. Each sculpture had been beautifully photographed by Michael – carnival kings and queens, mothers with babes in arms, strong featured young women as well as the weathered face of ‘The Duchess’, ‘the old man and the sea’, even a veiled nun.

“My heart ached as we came to the last photograph,” Rainer sadly recalled. “It was the smooth-skinned woman’s face turned pleadingly upward, eyes closed. “I titled that one ‘The Scream’, Socha explained to him. “I knew she would be my last sculpture, as the pain in my hands was so severe. I struggled for six months, and could have joined her in her scream to the heavens.”

Besides the continuous bronchial problems, Socha had developed an incurable neurological disorder, similar to Parkinson’s. Her hands had become progressively more uncontrollable, and the pain so bad that she had to alternate soaking them in ice water with every few minutes of sculpting. They were the ‘tools of my trade’ and it is understandable she would want to scream in desperation at their loss.

“Sooocha”, we sang out as usual, but there was no need for it today – she was already waiting for us at the door. We entered with balloons and beribboned champagne for this momentous occasion: The Book had arrived! (Socha: Sculptures) The text was in both English and German, with an introduction by a well-known German art critic, and a warm biography by Rainer. Socha opened to the page where Rainer had inscribed the first copy to her. Slowly she began turning the pages, her face beaming more radiantly with each one. Not only pride, but peacefulness came over this talented artist, as she saw her life’s work honored and preserved for the future.

“In this book,” she would write to Rainer, “you have brought me all my children....”.

Just three months later, Socha slipped into a coma; the doctor said it wouldn’t be long, and honored her wish to stay at home. Friends called or stopped by to check her condition with the nurse, but the patient remained unaware. However, late the second night she awakened at the ringing of the phone, sat straight up in bed, and carried on a perfectly normal conversation with Rainer, then fell back into a permanent sleep. An overwhelming demonstration of the power of their love.

Socha

Rainer