Stepping Up by Ronald Mackay

“Can you give a moment, please?”

The unexpectedly pleasant female voice stopped me in the act of mounting my bicycle to return to the city. My eyes took in the great, stone house of Balmuir and the lawn that stretched before it flanked by majestic horse-chestnut trees bearing their pink and white upright blooms as if they were so many triumphant candles. Mrs Bentley’s request afforded me the opportunity to feast my eyes on a scene I loved.

Minutes earlier, when I had arrived to deliver the prescription to Captain Bentley, his wife had been playing on the lawn with three of her sons. Respecting their privacy, I had directed my attention away from the family group beneath the chestnut blossoms and focused on the front door of the big house. From the window of his office, Captain Bentley had seen me arrive and opened the door even before I rang the bell.

Captain Bentley’s stern eyes seemed to take the measure of all about him including me, the boy who regularly delivered the family’s prescriptions by bicycle from the chemist’s shop in town. His martial bearing bred neither fear nor friendship but rather respect – respect for his naval rank, his class as landed gentry, and for an awareness that declared he had overcome more worldly trials than my tender years had so far prepared me for. His presence represented what I harboured an inarticulate desire to become – a thoughtful man at peace with himself, his family, and the pattern of fields and forests of the rural estate he himself managed and worked productively with two tenant farmers, labourers during planting and harvest, and Mr Tosh, the gardener.

My duty was to cycle the two miles from Dundee to Balmuir estate, make my delivery and cycle the two miles back to R.S. Duncan, Chemist and Pharmacist, so that I could make the other deliveries that awaited me as the part-time message-boy who worked daily after school from 4.15 p.m. until 6 p.m.

Instinctively I knew not to intrude on the privacy of his wife and children playing on the broad lawn, so it was with as much surprise as puzzlement that I wheeled my bicycle towards Mrs Bentley, obedient to her summons.

“You have attached toe-clips to the pedals on your bicycle.”

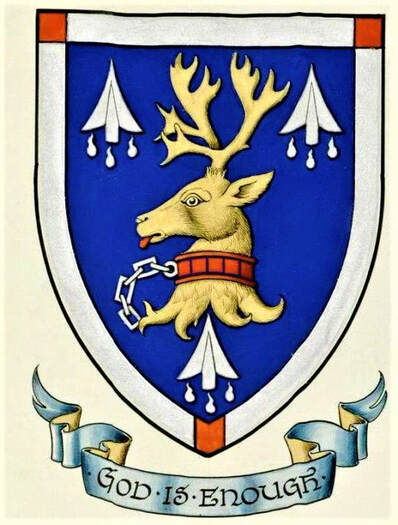

Mrs Bentley together with all her three sons were taking the measure not only of the toe-clips on the pedals of my bike but also of me. I drew my shoulders back and felt glad my hair was combed and the badge on my school blazer sported the antlered head of a stag, appropriate in this bucolic setting.

It was evident from her simple assertion that she had observed my arrivals and departures in the past as I went about serving one of the small needs of a rural estate-owning family. The unexpectedness of learning that I had previously been observed by a woman of her stature struck me as a mystifying compliment.

“I bought them several weeks ago and attached them myself.” At 14, I was proud to undertake the maintenance of my drop-handlebar, second-hand Dawes bicycle, my most prized possession. It took me to and from school rain and shine and made it possible for me to work as a message-boy every weekday evening except Wednesdays and a half-day on Saturday, for seven and sixpence a week.

“John wants toe-clips on the pedals of his new bicycle,” she gestured towards a clean-cut boy some few years my junior, “but I’m not sure that I approve.” Her tone suggested that she was seeking enlightenment to reduce her uncertainty.

I paused, used to being told things by adults not to being consulted. At my age, adults could demand my attention. But, unexpectedly and even more unaccountably, Mrs Bentley was politely requesting my counsel as if my opinion counted The fulfilment of her son’s hopes depended on my response. Her approval or its withholding hung on what I had to say.

Mrs Bentley stood relaxed and expectant as did John and his younger brothers. A thoughtful response was expected of me.

“Let me show you how toe-clips work.” Astride my bike, I supported myself on my left foot, slipped my right foot into the clip on the right-hand pedal and tightened the leather strap. I put weight on the pedal and as the bike was propelled slowly forward, I raised my left foot, slipped it expertly into its toe-clip and tightened the strap.

As a synchronous group, the elegant lady and the three young men rotated attentively as I made a slow circle round them.

“What’s the precise use of the toe-clips?” Her tone told of honest curiosity and the confidence that I could enlighten her.

“Without toe-clips,” I explained, “I can only deliver force to the bicycle chain on the down-stroke. With the toe-clips I can also exert force on the chain as I pull upwards with each foot in turn.”

“So, you can cycle faster?”

“Yes, toe-clips allow me to cycle faster but there’s an additional advantage. I’m using the energy of both legs more efficiently. Without the toe-clips, I waste the energy every time my foot rises.”

Mrs Bentley nodded her understanding. Delighted, her son looked expectantly at his mother.

“But isn’t there a danger?” A mother’s concern clouded her handsome face. “You are moving and have the toes of both feet strapped into the clips. What happens if you stop suddenly? Mightn’t you fall off? Injure yourself?”

I was conscious of enjoying this exchange. Honest curiosity on her part. Apprehension for the safety of her son. Confidence that I possessed the knowledge to allay her concerns. For the first time in my life, I became acutely conscious that much depended on how well and with what credibility I responded. A mother’s love for her eldest child. The abatement of her anxiety for his safety. The hopes of a young man on the verge of exploring his own boundaries and the responsibilities and dangers that inevitably accompanied making choices.

“Look at this,” I said. I repeated my demonstration and suddenly braked. As I did so, in one fluid motion, I pressed a flange on my right toe-clip, slipped my foot out and placed it on the ground to support my bike and myself upright.

The surprised appreciation on the faces of my elite audience pleased and flattered me.

“Each toe-clip has a quick-release flange. As soon as you touch either of them, your toe is released allowing you to slip your foot immediately to the ground. Of course, it takes some getting used to.” Now I was boasting. “With a few days’ practice, doing it successfully becomes second nature.”

I cycled round the group several times alternately tightening and loosening the toe clips. Now the left. Stop and release simultaneously. Left foot out for support. Now the right. Stop and release simultaneously. Right foot out for support.

Spontaneously, all four applauded my performance. I came to a halt in front of them feeling unusually appreciated.

“John, do you have any further questions for this young man?”

“No, Mother, his explanation is quite clear.” He smiled at me gratefully, trusting that I had put his mother’s concerns to rest. I felt proud to have won his confidence. “Now may I have toe-clips, Mother?”

“Yes.” Her answer came comfortably. “Thank you!” Her smile to me was appreciative.

***

I cycled back to R.S. Duncan, Chemist and Pharmacist, aware that I had been taken seriously by an adult other than from my own family for the first time in my life. I revelled in the conscious knowledge that I had been treated as a peer by those I had reason to admire, even revere.

My experience and understanding had been sought, assessed, found convincing, and acted upon. With her respectful request, her implicit acknowledgement of my expertise and gracious trust in my answers, Mrs Bentley had created the occasion that allowed me to take another step upwards on the precarious ladder towards maturity.

***

Mr Duncan was busy when I returned to the dispensary. He looked up, kind eyes questioning my new-found air of confidence. Powerless to find words adequate to my feelings, I could only return his smile. He turned back to the prescription he was preparing.

Ronald on right with friends and bicycle

Balmuir House