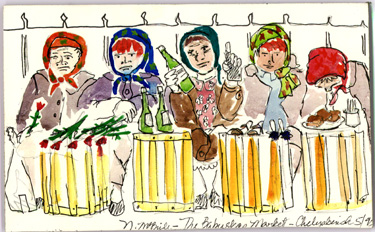

Babushka the Beautiful by Nancy McBride

Not long after Perestroika, I was invited to teach workshops in Storytelling at the Pedagogical Institute, and to lecture to several groups of business people, all in Chelyabinsk, Siberian Russia. My expectations were BIG:

1. To try a shot of Vodka

2. To NOT start an international crisis as a result. (I've learned to keep expectations simple, not low. As a result, I'm rarely disappointed and have more interesting adventures.)

My 78 year old landlady, who I immediately named "Babushka the Beautiful" (grandmother), became the protective guard dog of my rest, and stuffed me with an over-abundance of fabulous food created from fairy dust—my best guess. I got my shot of vodka by playfully pleading with her for a shot for medicinal purposes for my really sore throat. Da! Vodka. (Wodka!) Rolling her eyes, she telephoned a neighbor, and he brought vodka, staying for a convivial shot or two. Babushka, the nurse, personally shoved cotton with Vicks-like salve up my nose, for my cold (thank you very much), and every morning heated water for me to wash up with. (The hot water in that part of the city had been off for about 2 years.) She played the piano for me and slept on the floor at the foot of the daybed, my bed, and stopped her devoted care of me only to watch a Mexican soap opera, Marianna, on TV twice a day. She was deaf as a post, and spoke no English. I'm stone deaf in my right ear, and speak no Russian, so we communicated with no trouble, having more in common than not.

I was the weekend guest at a "resort" (more like an artists' colony) in the Ural Mountains, and ate, in a steamy cookhouse, the best soups, always with a dollop of sour cream on top. There I was honored with a shishlik (a goat was sacrificed right then and there for the bar-b-que), a banya (sauna, from scratch), and was taken target shooting. Totally inexperienced in this area, but undaunted, I found myself taking a surprisingly natural Annie Oakley stance, and I totally wowed them (and myself), hitting near bulls eye every time. Of course, having had beginner's luck, I took full guest advantage. I stood up, twirled the rifle, albeit ungracefully, blew the proverbial smoke off the end of the barrel, and then bowed.

When what life presented was a bit too far from my normal frame of reality, like my endless adventure on the primitive domestic Aeroflot Airlines with big, smelly dogs panting down my neck; or cats running out from nowhere to eat chicken bones discarded on the floor in a snack bar; or unspeakably gross public toilets, I privately chose to separate myself and be serenely starring in a Russian-style Fellini film.

I taught several storytelling technique workshops a day to college students learning to be English teachers or interpreters. I spent a lot of time with them. At least two of them interpreted for me everywhere but at my Babushka’s. Some were second generation victims of local nuclear accidents, and one young man, an excellent interpreter, told me tearfully that he was gay, and no one could ever know, because it was illegal. Another young man gave me his only photo of his family, so I'd remember him. I remember him.

I'd told my students they could ask me anything they wanted to, realizing that I was the only American they had ever met. And they did. Endlessly. One young man asked me if Jesus Christ was my Lord and Savior. I'd noticed posters everywhere of Western evangelists coming to save their "deprived souls" from the multi- generational Hell of non-religion.

I met with groups of business people at night. In informal conversations with their group later, they told me what was said in propaganda about us, during the Cold War. They couldn't believe why I'd come there at all, let alone not charged them for my work. These people were so warm and so generous. They were never our enemies.

There was the security guard who said he couldn't come home with me to protect me because his wife said, "Nyet!" But, she did say that he could give me his favorite military pin to wear to protect me, instead. Or the little boy, from the apartment upstairs, who, at my going away party, sang for me, in English, all the verses of the Beatles' "Yesterday," his father's eyes streaming with tears of pride.

I clarified that "America-the-Awesome" (to them) was a real place, with real problems with our education and health systems, and that the streets are often paved with credit, rather than gold, enabling us to acquire what we want, then to owe, with interest, compounded. I listened a lot, drawing out their dreams as citizens of a new democratic country, encouraging them, supporting their family values, the same, of course, as our own, but more like we remember in the 40s and 50s. I also became so very aware of their vulnerability.

Nine days in Siberia. Remember Siberia, the end of the earth? The place they send you if you're bad. I'd love to be sent there again. The people of Chelyabinsk captured a big part of my heart. It's been years and I think about the people I met there, often. I've travelled widely and never been so impacted. I feel I met my own people from the old country, and I'm Irish, Scots, English, Dutch, and Welsh!

When I left, “Babushka the Beautiful” shared the Russians' beautiful custom of saying goodbye and safe journey. We sat still, silently saying our goodbyes for a long moment. Then she abruptly nodded that I must leave now, turning away with tears in her eyes, as if she was sending me off, never to be seen again.

Be careful not to expect too much. Here or there. You may miss your Babushka the Beautiful.