NAVAJO SALLY and KOKOPELLI by Patricia Steele

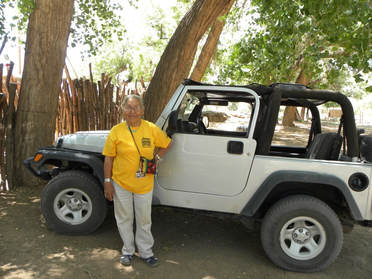

The Navajo woman’s aged façade emitted grit and strength and her Indian jewelry held strands of steel gray hair tightly in a bun. I was riveted to her tawny face, which was the color of aged whiskey. Her hand gripped the vehicle’s shifting post, a turquoise ring covered one finger from joint to knuckle.

Canyon de Chelly is in the Navajo Nation at the northeastern corner of Arizona. The cottonwood trees swayed above as our Navajo guide’s words immersed us in her culture. Her jeep was old. After crawling up on the back bumper, I climbed over the spare tire to find a foot hold. I threw one leg over the back seat and pulled the other one behind me as I slid downward. A broken seat belt… The woman backed up and took off as I grabbed the roll bar with one hand and my camera strap with the other. She was set on go and we were ready to roll.

Golden sand gusted and settled around me. My butt gripped the back seat of the open-air Jeep as I twisted and lurched, wishing my shoulder harness had a buckle to secure it into… Wind blew through my hair as I watched the intensity of Sally’s tawny-lined face in the rear view mirror. Suddenly, after passing fenced pastures filled with horses, bridles, saddles and a few people readying for a horse tour, the magnificent panorama opened up. High reddish-ochre, granite canyon walls rose above us in a huge expanse of sand, a silt meadow.

Startled, I was curious why two other Jeeps stood side-by-side ahead of us. Did we have to wait our turn to slip ahead? Before the question sailed through my brain, Sally braked, reversed gears and stepped on the gas…back, back, back until she braked suddenly again. What? Then she threw it into drive and lurched ahead…fast! We left the other vehicles in the dust so to speak. They were stuck in the sand! A few words later, I learned she’d been stuck only twice this year; when a vehicle gets slogged down into those 8 to 10 inches of soft sand, the wheels like to cuddle down and stop. So, she raced across the deep sandy stretches and said, “Hold on.” Without a working seat belt, the roll bar was my best friend.

The floor of the canyon was a surprise. A slight wind propelled dusty sand around us. Cottonwood trees were everywhere. Sally said the Russian olive trees had been removed because the canyon must remain clear for farming and tour traffic. Today, Navajo families still make their homes, raise livestock and farm the land within the canyon. Fencing was unique; small tree trunks and large branch stocks were used as posts. They were wired together to house horses, cows and to keep small animals out of their vegetable gardens.

Rolling across the ground between 20 and 30 mph felt like I was water skiing again. She avoided prior tire tracks by driving over their tufted edges to avoid sinking into the sand. Bumpy and smooth blended together, so judging when to grip the window ledge or the roll bar was tricky. Once, I actually flipped off the seat toward the open window on the other side of the Jeep. I found a foothold and wrapped the shoulder harness strap around my wrist, took a deep breath and raised my Nikon as we gazed up forever toward red and ochre rock walls. Of course I did.

Canyon de Chelly is in the Navajo Nation at the northeastern corner of Arizona. The cottonwood trees swayed above as our Navajo guide’s words immersed us in her culture. Her jeep was old. After crawling up on the back bumper, I climbed over the spare tire to find a foot hold. I threw one leg over the back seat and pulled the other one behind me as I slid downward. A broken seat belt… The woman backed up and took off as I grabbed the roll bar with one hand and my camera strap with the other. She was set on go and we were ready to roll.

Golden sand gusted and settled around me. My butt gripped the back seat of the open-air Jeep as I twisted and lurched, wishing my shoulder harness had a buckle to secure it into… Wind blew through my hair as I watched the intensity of Sally’s tawny-lined face in the rear view mirror. Suddenly, after passing fenced pastures filled with horses, bridles, saddles and a few people readying for a horse tour, the magnificent panorama opened up. High reddish-ochre, granite canyon walls rose above us in a huge expanse of sand, a silt meadow.

Startled, I was curious why two other Jeeps stood side-by-side ahead of us. Did we have to wait our turn to slip ahead? Before the question sailed through my brain, Sally braked, reversed gears and stepped on the gas…back, back, back until she braked suddenly again. What? Then she threw it into drive and lurched ahead…fast! We left the other vehicles in the dust so to speak. They were stuck in the sand! A few words later, I learned she’d been stuck only twice this year; when a vehicle gets slogged down into those 8 to 10 inches of soft sand, the wheels like to cuddle down and stop. So, she raced across the deep sandy stretches and said, “Hold on.” Without a working seat belt, the roll bar was my best friend.

The floor of the canyon was a surprise. A slight wind propelled dusty sand around us. Cottonwood trees were everywhere. Sally said the Russian olive trees had been removed because the canyon must remain clear for farming and tour traffic. Today, Navajo families still make their homes, raise livestock and farm the land within the canyon. Fencing was unique; small tree trunks and large branch stocks were used as posts. They were wired together to house horses, cows and to keep small animals out of their vegetable gardens.

Rolling across the ground between 20 and 30 mph felt like I was water skiing again. She avoided prior tire tracks by driving over their tufted edges to avoid sinking into the sand. Bumpy and smooth blended together, so judging when to grip the window ledge or the roll bar was tricky. Once, I actually flipped off the seat toward the open window on the other side of the Jeep. I found a foothold and wrapped the shoulder harness strap around my wrist, took a deep breath and raised my Nikon as we gazed up forever toward red and ochre rock walls. Of course I did.

|

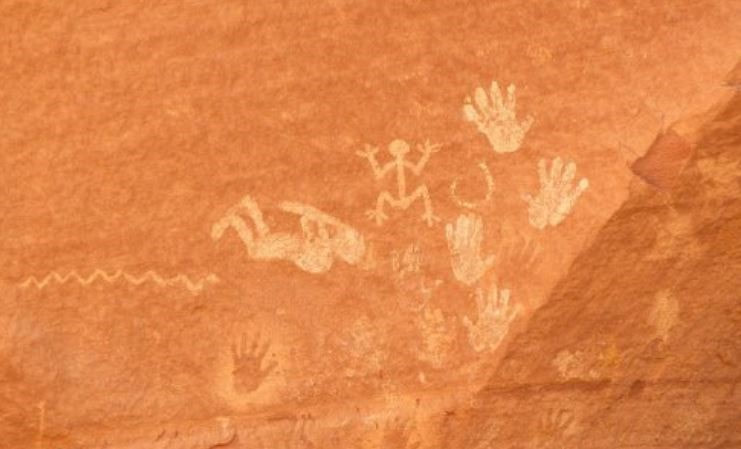

Dust devils slipped around us. More sand flew. The Arizona sun stoked the canyon walls. Sally’s voice softened when she talked of Navajo traditions, myths and stories while pointing out ancient pueblo sites and rock images on the sheer cliff walls. Homes were built into alcoves to take advantage of the sunlight and natural protection. With a small mirror to redirect the sun, she used it as a pointer to show us Anasazi petroglyphs[1] drawn by Puebloans centuries earlier. Her words were like a chant. We saw petroglyphs of hands, people, animals and objects. I was fascinated.

|

My breath caught when I saw the White House Ruin, the most complete group of ruins. Ochre-colored buildings were snugged on a high ledge with a lone, white building. I imagined a time when Puebloans walked, worked, played and loved.

As Sally proudly described her people’s past, I felt close to her mystical people and heard their music as we listened to the Navajo stories. Kokopelli was my favorite; he was the fertility deity, depicted as a humpbacked flute player. Despite being a trickster, representing the spirit of music, Kokopelli was a womanizer. Although history states that he carried seeds for agriculture and seeds of unborn children on his back to distribute them to women, Sally said he loved all women: He distributed seed, but they weren’t from a bag on his back…

The moon eclipse? Navajos believe their people should not stare at the moon. Tradition dictates that Navajos cannot eat during an eclipse or they will have stomach problems. They should not sleep during an eclipse because their eyes won't open again. Traditional Navajos do not look at an eclipse when pregnant because their unborn child may be born deformed. Pregnant women were actually covered during moon eclipses.

When our tour ended, I white-knuckled the roll bar when Sally sailed the Jeep back over the sand. Her jaunty Kokopelli whispered through my mind as we sped along that hot, sandy trip back to the real world. At the end of the day, I hadn’t flipped out of the jeep and I had a hundred photos. Despite my gritty hair riddled with sand and ripping my shorts when I slid out of the old Jeep, I still smiled. I found a silver pendant shaped like the naughty humpbacked flute player to remember Sally and Canyon de Chelly. And I imagine that impish character each time I slip it around my neck.

As Sally proudly described her people’s past, I felt close to her mystical people and heard their music as we listened to the Navajo stories. Kokopelli was my favorite; he was the fertility deity, depicted as a humpbacked flute player. Despite being a trickster, representing the spirit of music, Kokopelli was a womanizer. Although history states that he carried seeds for agriculture and seeds of unborn children on his back to distribute them to women, Sally said he loved all women: He distributed seed, but they weren’t from a bag on his back…

The moon eclipse? Navajos believe their people should not stare at the moon. Tradition dictates that Navajos cannot eat during an eclipse or they will have stomach problems. They should not sleep during an eclipse because their eyes won't open again. Traditional Navajos do not look at an eclipse when pregnant because their unborn child may be born deformed. Pregnant women were actually covered during moon eclipses.

When our tour ended, I white-knuckled the roll bar when Sally sailed the Jeep back over the sand. Her jaunty Kokopelli whispered through my mind as we sped along that hot, sandy trip back to the real world. At the end of the day, I hadn’t flipped out of the jeep and I had a hundred photos. Despite my gritty hair riddled with sand and ripping my shorts when I slid out of the old Jeep, I still smiled. I found a silver pendant shaped like the naughty humpbacked flute player to remember Sally and Canyon de Chelly. And I imagine that impish character each time I slip it around my neck.

[1] Photograph by Steve Finlay