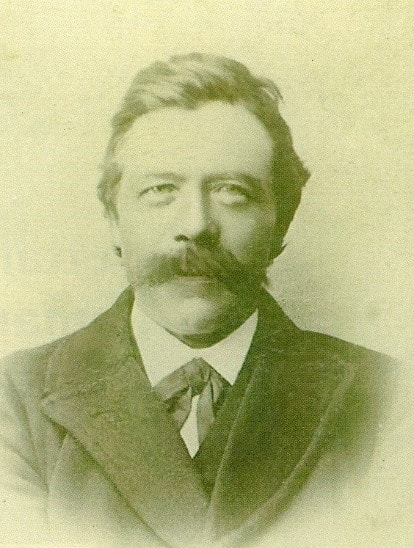

My Grandfather by Sverrir Sigurdsson

Excerpt adapted from Viking Voyager: An Icelandic Memoir, Chapter One, The Sea

My maternal grandfather, Þorkell Magnússon, was the captain of a fishing vessel called Gyða. In early April 1910, he and his seven-man crew, including his eldest son, set sail from Bíldudalur, a small town in northwest Iceland. Their destination was the rich fishing grounds beyond the fjord. April was the beginning of the fishing season, which lasted until September. These were the “mild” months. In reality, the weather was often stormy and below freezing, pushing both the boat and men to the limit of their endurance. Three weeks later, on April 23, Gyða headed for home, her hull laden with cod, the valuable cash fish many fishermen had died for. Nearing their home fjord, the men’s hearts must have lifted. A hot meal, a warm bed, and the family’s embrace were within a day’s reach.

That night, a furious northerly gale pounded the region with snow and sleet, whipping the sea into a deadly cauldron of crashing waves. All hands would have scrambled on deck to wrestle with the wind, jibing and tacking to keep the gusts from capsizing the boat. The battle went on all night. The next morning, Gyða was still upright and staggering closer to home. Einar, my grandfather’s neighbor and a former crew member, attested to seeing her from shore during a visit to his family’s farm on the outer reaches of Arnarfjörður (Eagle Fjord). The wind was still howling, pummeling the boat from left and right. But Einar was confident the boat could hold herself together. After all, Gyða was a sturdy oceangoing vessel, one of the first to be built in Iceland with state-of-the art technology. In just a few more hours, she would reach the safety of the harbor.

The next day, Einar found berth on a vessel that took him home to Bíldudalur. As his ship sailed into the harbor, he looked out for Gyða. He knew she was no longer out in the fjord, for he had sailed the length of it and hadn’t seen another ship. The only place Gyða could be was home, at Bíldudalur. He scanned the half-dozen ships docked in the harbor. To his dismay, Gyða wasn’t among them. With a sinking feeling, he knew what must have happened. The fjord had swallowed Gyða and her crew.

In the spring of 1954, I sailed from Reykjavík on the coastal vessel Esja to Bíldurdalur, my grandfather’s hometown. The sea was mirror calm as the ship’s powerful twin diesel engines propelled her into Arnarfjörður, the scene of Gyða’s disappearance. This fjord was notorious for squalls that could come up without warning. But that day, it welcomed me and the other 170 passengers with a gentle embrace. The water was a sparkling blue satin cut from the same fabric as the sky. My fifteen-year-old self stood near her bow, marveling at the panorama of steep, snow-flecked mountains that rose abruptly out of the sea. Looking down, I was mesmerized by the thousands of jellyfish pulsating out of the way of Esja’s knife-like bow.

A year earlier, a shrimp trawler combing the bottom of the outer reaches of Arnarfjördur had hauled in a huge pole. Forensic analysis determined that this had been the mast of Gyða. The town decided to erect a monument, using the mast as the centerpiece. I was one of the relatives of those who perished on Gyða to attend the unveiling of the memorial. My mother and I, together with other family members, went to pay respects to Gyða’s skipper and her crew.

I tell this story sixty years later from my home in Virginia, across the Potomac River from the U.S. capital. I am now in my eighties, retired and carefree, with nothing better to do than pamper my grandchildren and tell them stories of my life. But they are too young to fully appreciate them, so I write them down for the time when they reach my age, when they are retired and carefree and want to record their own stories. As they search their memory, an eerie feeling that their lives aren’t just the sum of their own experiences will haunt them. Strands of other people’s memory will swirl in their heads, speaking in voices some of which they recognize and others not. They will find out life is a relay, every leg a continuation of the previous one. To understand themselves, they have to understand those who have gone before them.

I was born in the hallway because of an overflow at the hospital in Reykjavik that night. I arrived at that time and place because of the confluence of the voyages my parents, grandparents and all the previous generations had taken. My parents named me Sverrir Sigurðsson. The last is my patronymic surname, which identifies me as the son of Sigurður, my father’s given name. Sverrir means swordsman, a name of the Viking era.

From an early age, I knew I would go on a voyage of my own, but I had never dreamed of reaching such distant shores as the Middle East, Africa, the Asia-Pacific region, and America. These travels have given me a great sense of fulfillment, but they are insignificant compared with the miraculous progress my people have made within my lifetime. I have the satisfaction of seeing my country thrive during the renaissance born of the most destructive war in human history, and rise from being one of the poorest nations in Europe to one of the most prosperous. There were many occasions in our thousand-year history when volcanic eruption, disease, and prolonged winters drove our tiny nation to the verge of extinction. We survived, though barely. Thanks to the new postwar order, we made a quantum leap, joining the ranks of the world’s advanced nations in a matter of decades. During this time, our population swelled from 120,000 to 350,000, and many a survey named us one of the happiest people in the world.

But I don’t want to forget the hardships. My ancestors’ endurance is my strength, in the same way Icelandic winters have seeped into my veins and inoculated me from the cold. My American friends poke fun at me for running around in shorts when they’re shivering in jackets. So, I start my story by dwelling on the hardships—the sinking of Gyða and the loss of two family members that fateful day. My grandfather was forty-five at the time. His oldest son, Magnús, eighteen, was the mate. A merciful turn of fate spared his second son, Ólafur (Óli), who was fourteen. He had been fishing alongside the men since the age of ten, but that spring, he had to stay behind to complete his school-leaving certificate; otherwise he would have been on board Gyða too.

My grandmother, Ingibjörg Sigurðardóttir, became a widow at forty-two. She had four surviving children, ranging from sixteen to an eighteen-month-old, my mother. Gyða’s disappearance shattered my grandmother’s life. In one fell swoop, she was transformed from managing a relatively well-off household in a prosperous town to a destitute widow with four children to feed. The two breadwinners were gone, and there was no insurance or other source of income to ensure the family’s future.

To put the tragedy in a broader perspective, the loss of eight men out of a total of 270 residents in the town of Bíldudalur represented almost 3 percent of the population. And this wasn’t all. A couple of months later, the fishing boat Industri, from an adjacent town, disappeared in a gale. The crew of ten included Einar, the last man to see Gyða, and his thirteen-year-old son. The families mourned, the town mourned, and life limped on until the next tragedy.

My Grandfather

The vessel Gyða

Bíldurdalur, my grandfather’s hometown