When Cutty Sarks Run in Your Mind by Ronald Mackay

Brenda was a thief.

No, not a professional burglar, housebreaker, embezzler nor mugger. Neither did she employ a troop of under-age pickpockets to steal what she wanted.

But Brenda was a thief, nevertheless. She, herself, boasted of her exploits without a trace of shame.

She’d seek out, she told me, an abandoned farmhouse or barn – there were lots of these in Ontario in the ’60s and ’70s -- and, at an hour nobody was likely to be about, she’d purloin ancient hand tools and use them as decorations. If original hand-forged, wrought-iron hasps still remained on doors, she’d strip them off to give her own place a more traditional look.

Sometimes, she bragged, she’d be more daring. At farm sales, where a retiring couple’s life possessions were laid out on the lawn and the auctioneer stalked from one lot to another encouraging bids from city-folk, she’d ‘acquire’ her most valuable items.

While the crowd’s eyes and ears were with the auctioneer and bids were rapid, she’d stand with her back to an antique chest of drawers or a stack of old doors, reserved to be sold later when the less valuable items had gone. As bidding reached fever pitch, she’d skilfully unscrew brass fittings or porcelain handles and slip them into her pocket. Then, mission accomplished, she’d distance herself from the violated item and mingle with the crowd.

Before the item from which she’d stolen the most valuable part, was auctioned, he’d slip away.

***

“There’s a threshing floor in there!” Brenda was pointing to an isolated barn on the farm property that adjoined hers. “The boards are rough-cut, twenty inches wide and two inches thick. They must have been cut by the first settlers from white pines growing on the property. You don’t find trees that big around here anymore.”

I had a sinking feeling Brenda was about to come up with a proposal.

“These boards would make a perfect floor for the shed you’re converting into a doghouse for my sighthounds.”

In my spare time, I did odd jobs around farms, mainly for city people with few skills and full wallets. Brenda was a city girl who’d taken to rural life, the better to accommodate her love for breeding hounds and add to her prestige in the eyes of those who sought puppies, and in her own.

Although Brenda didn’t dip easily into her pocket, I’d done first one job and then others for her. My interest was less in her wallet than in the more eye-catching attractions she possessed in abundance. Subtly, tantalisingly, she dangled the promise of joys-to-be just out of reach, though her attitude suggested that they might not be withheld forever.

So, I’d stuck around, doing jobs. Sometimes charging. Sometimes not. Hoping.

***

She’d inherited, rather than acquired, her penchant for pilfering. She belonged to a sophisticated family with a love of – an obsession for-- beautiful things. Her mother, who occasionally visited, would reminisce over how she had acquired a set of rare 18th century hand-painted tiles, or a nest of tables whose walnut surfaces were inlaid with mother-of-pearl, or a painter’s self-portrait.

Invariably, the stories of how such works of art had been obtained involved if not downright skulduggery, at least morally questionable skills.

***

But back to Brenda.

“There’s a threshing floor in that old barn. The boards are loose. I’ve checked.” She looked at me in such a way as to suggest that what particularly interested me about her might no longer be remote – certainly not entirely unobtainable.

“I could find out who the barn belongs to and make an offer on the boards.” I offered.

She placed her hand on my forearm. I felt its warmth.

“If you were to stay here tonight, you could, just before dawn, get the boards without attracting attention.”

***

After a divinely sleepless night and just as the June sky hinted at dawn, I made my way, alone of course, across her fence, through the deep grazing in the neighbouring field and uphill to the long-abandoned barn.

Two-stories high, it had been built in the late 1800s on a slope so that the lower part could serve as the stable for cattle and the upper part as storage for winter hay. The upper floor was divided into two high mows, now long empty. These mows were separated by the threshing floor where the itinerant threshing machine would have taken the grain off the sheaves of wheat or oats before moving on to the next farm.

The boards laid on the threshing floor were things of beauty.

***

One by one – they were immensely heavy – I carried them out of the barn, down the slope, through the fresh grass, over Brenda’s fence, and stacked them outside the shed I’d almost completed as her new doghouse.

Brenda met me with a smile and a cup of sweet coffee just as I placed the last of the eight boards onto the neat pile.

“Now…” she smiled.

‘Now, back to bed to pick up where we left off,’ I finished her sentence in my mind.

But I was wrong.

“Now, you’d better get these bords cut to size and laid inside the doghouse. It would be unwise of you to leave them out here for just anyone to see.”

***

Two hours later, I’d cut each board to size and the floor was laid.

‘Now it’s my turn,’ I straightened up.

Brenda’s smile was angelic.

“Now…” she began.

I made for the house.

“Now, we can’t leave these remnant pieces here for anybody to see!” Long-practiced larceny had made Brenda cautious.

***

Half-an-hour later, I’d run the saw through the off-cuts and split them into kindling. Now the woodshed contained an anonymous stack of blocks and split kindling to start the woodstove in winter.

‘Now!’ I was just heading back to the house when a sleek black car bearing the logo of the Ontario Provincial Police came to a halt in the yard.

I knew Paul. As well as an OPP officer, he was a part-time farmer and lived close by.

The smile slid from my face as he reached back in for his officer’s cap and adjusted it squarely before looking at me.

He is not bringing you good news when your friend the police officer finds it necessary to don his uniform cap before saying ‘Good morning!’

***

“I’m investigating a complaint.” He didn’t use my name.

“Oh?”

“When the farmer who rents the neighbouring land as pasture checked the barn this morning, he found the boards from the threshing floor missing. Know anything about it?”

Paul was looking up the hill at the barn. A deep path of trampled grass led from Brenda’s fence line to the barn and back.

I remained silent.

“Know anything about it?” Paul raised his eyebrows.

Might Paul pretend he hadn’t seen the beaten path? Of course not!

From where we stood, we could see the neighbour who rented the land as summer grazing watch us from the furthest end of the path I’d beaten through his pasture.

***

“Look!” I walked Paul to the doghouse.

Paul admired my handiwork.

“The barn’s been abandoned for years. The owners left for town when the house burned down. The land’s rented as a ranch for pasturing beef cattle.” I was repeating Brenda’s words.

“The tenant told me he’s responsible for the land. And the barn. And the threshing floor boards. He called the station as soon as he discovered they were gone.”

I gulped.

“He’s officially reported the loss to the OPP. He’s reported it to the owner. I’m the investigating officer.”

This, I could see, was getting more complicated by the minute.

I decided to look for a positive way out.

“How can I resolve this?” I asked.

“If the owner decides to press charges, the charge will be ‘theft under two hundred dollars’.

I felt the chill fingers of the law clutch at my heart.

“If?” I added hope to my voice.

“I’ll tell you what I’ll do.”

A ray of hope?

“I’ll visit the owner. She’s 89. A widow, now. I’ll tell her you’re willing to replace the boards or offer financial compensation.”

“I would appreciate that.” I meant it. I couldn’t replace the exact boards. I’d reduced them to flooring for a doghouse and the off-cuts to stove kindling. Today, lumber yards sold finished lumber that was never more than ten inches wide. I hoped she’d opt for the money.

Paul turned his car around and sped off back down the lane.

For the next hour, while I just waited, romance was the last thing on my mind. In any case, Brenda hadn’t shown her face since the arrival of the police.

***

On his return, Paul stepped out of his vehicle and, again, adjusted his cap. That gesture seemed as ominous as a judge donning a black cap before announcing a death sentence.

“I spoke to the owner. She knows you can’t find boards to replace the originals, so she’s willing to settle for money. She won’t take less than $400. Deliver that in cash to her house this afternoon, she’ll call me to confirm, and we can all forget this whole thing.”

“No charge?”

“There’ll be no charge. Once you’ve paid, the matter’ll be forgotten. But, remember that a barn – abandoned or not – is private property. Removing anything from private property without permission is a criminal act.”

***

As soon as I returned to my own home, I took the collected works of Robert Burns from my bookcase and read the final stanza of Tam o’Shanter:

Now, wha this tale o' truth shall read,

Ilk man and mother's son, take heed,

Whene'er to drink you are inclin'd,

Or cutty-sarks run in your mind,

Think, ye may buy the joys o'er dear,

Remember Tam o' Shanter's mear.

Ilk man and mother's son, take heed,

Whene'er to drink you are inclin'd,

Or cutty-sarks run in your mind,

Think, ye may buy the joys o'er dear,

Remember Tam o' Shanter's mear.

***

I pondered how pursuit of “cutty-sarks” -- miniskirts in English -- or in Brenda’s and my case, no skirt at all, are as liable to lead an honest man astray today as they were in the time of Robert Burns.

I pondered how pursuit of “cutty-sarks” -- miniskirts in English -- or in Brenda’s and my case, no skirt at all, are as liable to lead an honest man astray today as they were in the time of Robert Burns.

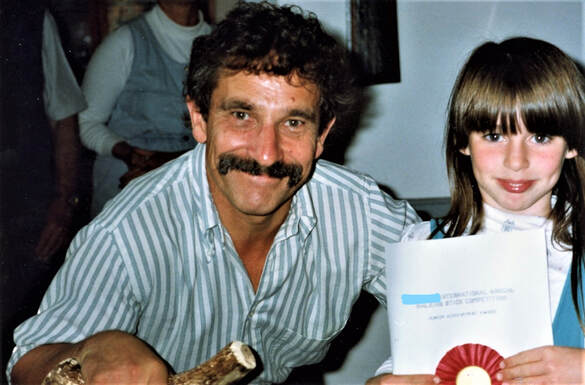

Ronald presenting a Junior Farmer award in Ontario in 1986