Elegy for North Fork by Leslie Groves Ogden

Hot, thirsty, and tired of driving, I braked cautiously and left the highway. Gravel crunched as I steered onto the familiar campground road. The jagged mountains of central Idaho loomed on the horizon, and in the distance we could hear the peaceful babble of the Wood River. After a two-day, thousand-mile journey, my sister Susan, my husband Barry and I had arrived at our favorite vacation spot, North Fork Campground in the Sawtooth wilderness. It was July, 1998, and our first trip to Idaho without the rest of the family.

Glancing in the rearview mirror at Susan’s car, I stuck my hand out the window and pointed toward campsite 18, located around the bend and past a big aspen grove. She nodded and followed us down the narrow lane toward the river.

As we emerged from the trees I blinked. Had I somehow taken a wrong turn? What happened to the road? We stopped and got out, staring openmouthed at the scene before us.

The gravel road disintegrated into a rocky, weedy, driftwood-strewn path. Sentinel pines reached skyward, but young cottonwoods and river birch lay dead or dying, their branches twisted, broken, and tangled. Boulders of every size littered the ground. No sign remained of campsite eighteen’s picnic table, fire ring, or water faucet. Beyond, the river flowed swiftly between vertical banks, apparently having devoured its sandy beach.

The sight awakened a lifetime of memories. I was seven or eight the first time I remember camping here. We pitched Dad’s heavy World War II army tent on the beach. It didn’t have a floor, so we unrolled a big canvas tarp and threw our army surplus sleeping bags on top. The tarp smelled like motor oil and felt slightly greasy, but it was better than sharing our beds with river ants that lived in the sand. Dad pounded huge stakes into the ground to anchor our shelter against occasional summer thunderstorms.

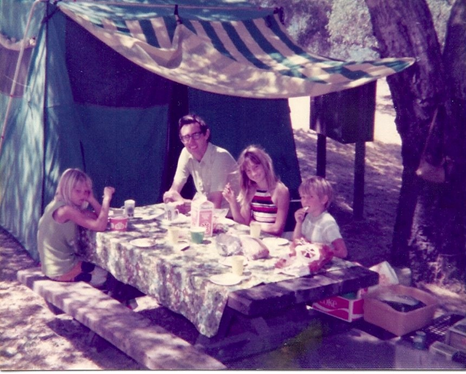

Long before we vacationed here as a family, Mother and Dad, newlyweds in 1937, drove the ninety miles from their home in Twin Falls for weekend fishing trips. In the early 1930s the WPA had constructed roads and dug privies at North Fork. Workers leveled campsites, installed a water system, and built picnic tables and fire pits. As soon as Susan and I were old enough, Mother and Dad took us camping.

Our Idaho vacations did not stop when we moved to California in 1950. We’d return in summer, secure our spot at North Fork, and invite our Idaho relatives to join us. Mother preferred to visit without imposing on anyone.

In the 1960s I introduced my new husband to the beauty and peace of the Sawtooth. Accustomed to noisy, crowded, parking-lot campgrounds in California, he adjusted easily to Idaho’s serenity. In campsite 18 we enjoyed a private stretch of beach and river. We couldn’t see our neighbors, and if they made noise, the river’s music hid it. As our children grew up, they learned to catch and clean trout, pitch a tent, observe giant anthills that we never saw anywhere else, and make s’mores over the coals of a dying campfire. One summer they created a retreat on a small river outcropping formed by a wayward current. It included driftwood furnishings and a secret food cache. They named it “Fun Kids Island” and still reminisce about it forty years later.

My gaze returned to the ruined campsite. How wild and furious the river must have been, to violate its boundaries with such force. I remembered how those sudden summer thunderstorms would send us running for shelter. The Wood River Valley gets around 23 inches of rain annually, and we often experienced brief rainstorms during our visits.

On one memorable occasion, Barry and I and the children were asleep in our big canvas tent when a midnight storm unleashed its fury upon the North Fork campground. We had lashed a large plastic tarp to the roof in anticipation of rain, expecting we would remain snug and dry lying on our foam pads, wrapped tightly in our sleeping bags. However, the sloping design of the tent roof allowed water to accumulate on top of the tarp, and when a loud roll of thunder awakened us, we sat up and discovered the ceiling was suspended mere inches from our faces. The tarp was totally waterproof, but the rain collected there as if it were a cistern.

As the storm raged outside, we considered our predicament. The water’s weight would soon bend or break the aluminum tent poles holding up the roof. But if we pushed on the ceiling, water would cascade down the sides of the tent and settle beneath the floor. Having few options, we gingerly poked at the roof, hoping to lessen the burden a cup at a time. It seemed like we knelt there for hours. With each thrust, water gushed downward and saturated the ground under the tent. Before long we could feel wetness penetrating the tent floor and seeping into our foam mattresses. We were cold and exhausted and very grateful when finally the storm seemed to let up. The children had slept through the entire ordeal, although all of us emerged from the tent that morning wet, chilled and cranky. We built a roaring campfire and kept it going most of the day, trying desperately to dry our bedding before nightfall. The tent poles had survived the stress, and we were able to move the tent from its muddy location to a grassy area beneath the shelter of a couple huge whitebark pines. However fierce that long-ago storm had been, in the morning the Wood River flowed serenely and the campground, although damp, had no signs of damage.

In all the vacations that our family had spent here, beginning in the 1930s into the 21st century, the kind of destruction that we were witnessing today was inconceivable. Silently, Barry, Sue and I clambered over logs and debris toward the water. Our favorite fishing hole near campsite 5 was barely recognizable. We stopped at a place where we used to set out lawn chairs. We’d sit in a patch of morning sunlight, sipping coffee and watching the ouzel birds emerge from their riverbank nests to walk under the water, seeking a breakfast of water insects and worms.

Today, the river idled placidly here, belying its recent fury. We tramped along the water’s edge, noting how the current veered in new directions, undercutting the bank and creating unfamiliar berms and ledges. Beavers had already claimed a downed tree, using the trunk to anchor their new dam.

The afternoon waned and we needed to pitch camp. Walking back to the campground, we discovered several open, grassy sites far from the floodwater’s destructive reach. We found a convenient place and unpacked. After setting up tents, organizing our gear, and eating a quick, cold dinner, we admired a spectacular orange sunset.

Relaxing in our lawn chairs by a fading campfire, we listened to the river rushing by in the distance. Giant red cedars towered overhead. A soft wind brushed my cheek and rustled aspen leaves. A patch of purple-blue lupin flourished nearby, and I detected the pungent licorice scent of Sweet Cecily wildflowers. My senses murmured, “Idaho”.

Maybe tomorrow, we would look for ouzels.