From the solitary gloom of his office on the second floor, Campbell looked out at the snow. It lay pristine inside the compound, crushed brown in the street beyond the tall iron railings. He watched as Dave, one of his two men acting as embassy guards, entered the second building within the compound. A carriage house and stable for this once grand house, it now served a different but no less important purpose. The door closed behind him.

Campbell looked at his watch. Another three hours, at least.

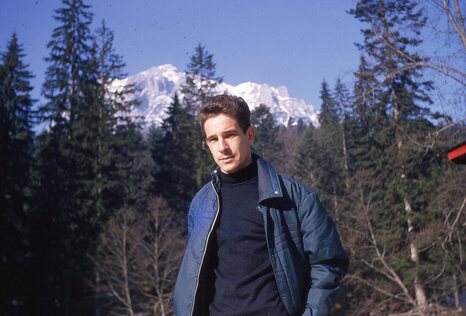

Comfortable at his window, he allowed himself to reflect. He was satisfied with what he’d accomplished since arriving at Otopeni Airport in October. London had pushed the doctors at Guy’s Hospital to clear him fit for duty but they wouldn’t release him till his wound had healed to the point where it no longer put his life in danger in the field. London had been unhappy. They needed him in place now! Gheorghiu-Dej's death in March 1965 had taken London by surprise. By even greater surprise when, just a few days later, Nicolae Ceaușescu took over as Secretary of the Romanian Communist Party. Now there was the possibility that Romania might stray from its role as the USSR’s most subservient satellite. London had been searching for an opportunity like this since ‘49 and wasn’t going to miss this one.

“You’re going in! Clean. Build a network. We need HUMINT. Fast!” Central spoke and Campbell had acted accordingly. Seventeen years in the field had taught him everything. ‘No,’ he thought. ‘Not everything. Never everything. There’s always a new way for a wheel to come loose. But how best to recruit, train and deploy; to provide London with what it needed to sketch out and revise its political and economic ‘what-if’ scenarios, that, yes!’

Markov’s bullet in Berlin had ended his career as a field agent. Released from rehabilitation a few months after Ceaușescu, the cobbler-turned communist rabble-rouser, replaced Georgiou-Dej, he’d taken up the cover appointment in September. ‘First, get your own house in order,’ the agent-runner’s primary task. He’d switched two of the existing British guards for two of his own men. ‘Keep your house in order,’ was the second. That was the hard part. Cautiously, he’d cast around for potential. The hardest task of all, finding potential.

***

A movement broke his reverie. Two Romanian guards emerged from the sentry box hard up against the railings on the street side of the embassy, stamped their feet, lit up and stood smoking. As they turned, he saw utter boredom engraved on their faces and filed a mental note. ‘Boredom: to be turned into an asset.’ Mental notes were central to Campbell’s routine. ‘Good field habits tip the scale in favour of survival.’

‘Two sets of guards,’ he mused. ‘Chalk and cheese. Bored uniformed Romanian soldiers visible to the public -- their job to keep a paper record of all comings and goings to and from the embassy for Securitate. Low-key, apparently laid-back British guards to monitor security within the compound. His two, capable of other duties well within their training and experience when needed. Dave and Bob reported to him alone.

Back at the polished desk, bare except for an immaculate blotter, Campbell took stock. Snow was called for. Snow in the plain meant more higher up in the Carpathians Even more on the hillside overlooking the railway line through the valley at the point where the hand-off was arranged. Yet another challenge to add those that accompanied any covert mission even one as simple, at least on the surface, as this. Campbell was acutely conscious that this was his new agent’s first. And, especially on the first, Murphy’s law reigned.

Two months back, both at the same time, two reports had reached London from separate residents, one in Kyiv in the USSR, the other in Constanza on Romania’s Black Sea coast. Kyiv reported unusual, regular activity at a railyard on the river Dnieper close to Vyshhorod. Long trains of close to a hundred railcars were being assembled at weekly intervals. Put together in three sections. In the middle, ten loaded flatcars, crates covered by grey tarpaulins. Always ten, always tarped. To either end, forty boxcars – always forty -- were hooked up. Two powerful locomotives were attached front, and two in the back. Ninety railcars long, the train would pass Kyiv around midnight on a Monday and head southwards to the Romanian border.

From Constanza, the agent there began reporting mobile cranes transferring crated cargo from a short train composed of ten tarped flatcars. They swung crates onboard a ship on Wednesday mornings. Tight security prevented the agent from learning the nature of the cargo. But it was heavy.

London became excited. ‘Investigate connection between the two reports,’ came the demand. ‘Identify cargo.’

Campbell had taken a deep breath. ‘The very opportunity I’ve been waiting for. This can serve as Balfour’s test.’

*****

“Before you leave…?” Campbell recalled Balfour’s reaction as he was signing out of the embassy after a routine visit to the cultural attaché, Tony Man. “Can I interest you in a weekend of cross-country skiing?”

“I’d love to.”

But Campbell noted the hesitation. It was, he judged, to the lad’s credit. Like several other matters, Balfour had omitted cross-country skills from the curriculum vitae demanded by the Foreign Office when he’d submitted his application for the post of exchange professor in soil science at Bucharest University.

“Good. We’ll stay at the embassy villa. Boots and equipment there. You’ll find your size. We’ll go easy. I’ve almost recovered from a fracture.”

The British Embassy had had a villa on an isolated mountainside in the Prahova Valley for decades. Since Romania had become communist and a satellite of the USSR after the War, the villa had become even more popular with embassy staff at weekends. It was their opportunity to escape from the boredom of Bucharest -- lives confined by their diplomatic status and the Securitate, Ceauşescu’s Secret Police.

Of course, Securitate always knew where diplomats were. Romanian guards outside all Western embassies recorded comings and goings. National police were charged with spotting any car bearing CD plates then phoning their observations to a special 24-hour office at Securitate headquarters. An easy task in a country with no private cars. The few cars on city streets and the even fewer on roads in the countryside belonged to the state and were used by only a few senior members of the Communist Party. They were Russian ZIM-12s, shiny-black and polished chrome, imported from the Gorky automotive plant east of Moscow. Most other cars, and there were few, were owned by the staff of Western embassies, easily identified by brand and numbered CD plate. It was simple for Securitate to keep track of the whereabouts of all Westerners so long as they were in a car. Skis were a different matter.

***

Campbell’s initial weekend cross-country ski invitation to Balfour had turned into regular mid-week expeditions, always on Wednesdays and Thursdays. The exercise challenged his injury but his earlier excursions undertaken alone had satisfied him that his condition was returning. They’d also served to satisfy his principal need -- to discover the route of the long train from the northern border. It hadn’t been hard to find. It wound its way down the only track in the region through deserted, tree-clad mountains and then diverted east through the Prahova Valley on Tuesday afternoons. But he needed time with the lad in the terrain where the operation would have to be undertaken and to assess his suitability quickly before drawing his or anybody else’s attention to this particular train. Balfour still hadn’t been given access to the laboratory in the faculty of soil science at the university and so he was happy to fill in time mid-week that would otherwise be unproductive.

On skis, he'd chosen various routes from the villa but always, and from different directions, Campbell saw to it that they encountered the same tight curve on the track through the pine forest. He’d stop and they’d rest in silence. From dense wooded cover that smelled of resin, they’d watched sundry engines, railcars and guards’ vans pass so close that they might have reached out and touched them. Intentionally, he’d waited till Balfour remarked on what had become an implicit routine.

“This loop in the line fascinates you.”

“Why might that be?” He looked directly at the young man.

Balfour held his gaze. “A tight curve. Unusually tight. The train has to reduce speed. The lead locomotive disappears round the tight bend, then we can see only freight cars until the guards’ van or a rear locomotive passes at the end.”

“Go on,” he’d been hoping for exactly this insight.

“Even if the train’s short, the middle cars are invisible to both the drivers and guards, but only for a few seconds. But when the train’s a little longer...” He paused. Campbell nodded encouragement.

“Well,” he paused again, uncertain. Again, Campbell nodded his encouragement. “If someone wanted to board a railcar without being seen, this would be the ideal spot.”

“Why would anyone want to board a railcar en route from the north to who-knows-where in southern Romania?”

“To find out what the cars contain?”

Campbell raised his eyebrows as a question.

“It might be someone’s job to find out that sort of thing.” Then Campbell knew the lad had the potential he was looking for. He inclined his head in assent. There was no need for either of them to say more. Each looked at the other with a new understanding, a new intimacy. They’d skied the fifteen kilometres back to the villa in silence.

***

That evening, Campbell told Balfour all he needed to know. It wasn’t much.

“Slàinte!” he poured two glasses of Glen Deveron single malt, pushed one towards Balfour and raised his. Their eyes met in a newly-formed bond of mutual trust. But trust, Campbell knew, was as fragile as any other human relationship.

“I want you to come out here to the villa on your own several times.”

Balfour nodded.

“Mondays. I’ll arrange for you to borrow the consul’s car. Securitate only track you as far as the villa. At dawn, you’ll ski out to the loop, take cover and observe. Before noon, a freight train drawn by two locomotives will come through. Observe how it’s made up. Locomotives, type and number of freight cars.” He stopped. Brought the glass to his lips.

“That’s it?”

“For now.”

Balfour nodded.

“You can say no. Either way, this conversation goes no further.”

“I’ll do it. Condition understood.”

Balfour hadn’t hesitated. Campbell took mental note.

“Next Tuesday. Then the following two. The afternoon after each operation, you’ll drive back to the embassy. Dave will be on duty. He’ll sign the return of the car. He’ll hand you paper and pencil. Write down your complete observations. No voice, the embassy’s bugged. Leave the paper with Dave. Then go about your business in the university as usual.”

***

Balfour had undertaken the task three times. Three times he’d confirmed two diesel locomotives up front, forty boxcars, ten tarped flatcars, forty more boxcars and two locomotives in the rear.

The following weekend, at the villa with others from the embassy to enjoy downhill skiing at Sinaia, Campbell took Balfour out onto the privacy of the snow-covered deck after dinner. “Next time, confirm the make-up of the train, but also focus on two things. Look at how a man might safely access the platform of each of the ten flatcars from the ground. And calculate for exactly how many seconds the flatcars are out of sight of the front and rear locomotives.”

He’d watched Balfour finger the glass in front of him. Seen the curiosity in the lad’s eyes. Knew he wanted more. But Balfour had only nodded.

“All in good time.” Campbell said the words as reassurance. They meant, ‘I know how you feel. Trust me.’ An agent had to learn to live with a certain level of uncertainty. “And estimate how far round the curve a man might be taken between boarding for ten seconds and alighting.”

Balfour nodded.

***

It had taken time for London to arrange for the flatcars to be photographed at the point where the train halted briefly between the USSR and Romania. London told Campbell only that the camera used to take the photographs, with the film still inside it, would be securely placed under the tarp on the hindmost of the ten flatcars and the date.

“Retrieve the camera and film. Send both to London with the next flight of Queen’s Messengers.”

It had taken time for Campbell to analyse the information Balfour brought back. He’d gone over every piece of it with the lad. The time the flatcars were out of sight of the locomotive drivers. The speed of the train on the curve. How best for a man to grasp and raise himself onto the steel bars that gave access to the flatcar from the ground. The time it might take a man to search for and retrieve the camera under the tarp. How far round the curve a man would be when he lowered himself to the ground.

After going over these details exhaustively, Balfour had queried, “A man?”

“Can you do it? Will you?”

“Yes.”

It was the response Campbell needed.

***

Campbell walked from his desk back to the window. He looked out but saw nothing now. He was up there in the trees on the snowy mountainside. He imagined his agent in the planned spot, camouflaged, motionless, anticipating the train with every fibre of his body. Two minutes to accomplish the task. Emerge from the trees, board the flatcar, find the camera, stow it safely on his body to leave both hands free, get back down to the rail bed and into cover. One hundred and twenty seconds.

Campbell withdrew from the window. He recognized the feeling of heightened awareness that accompanied all field operations.

‘Agent?’ Campbell wondered at his use of the word for Balfour. ‘Why do I already think of the lad as an agent? He was just a student until a few months ago. Now he’s an “exchange” soil scientist in a faculty that only accepted him so that one of its own scientists can spend a year at Reading University.’

Nevertheless, Campbell had a hunch. If Balfour pulled this field operation off successfully, if he didn’t panic at the last moment and chicken out, if he didn’t fall under the wheel of a railcar as he alighted, he would have earned the title.

‘As an agent, I’ll have far more challenging tasks in store for him.’ He thought of himself twenty years ago. There was something about the lad that reminded him of himself at that stage of life.

Then Campbell checked himself. ‘He’s merely a means to an end.’ He turned back from the window. Back into the moment. He knew better than allow himself to consider any new recruit as more than a disposable means to a necessary end. Intelligence gathering brooked no sentimentality. If the lad fouled up, as far as London was concerned, he was replaceable.

*****

Carpathians

Prahova Valley