WINDFALL:3 Ráhel, Trudy, Ivan by Ronald Mackay

As Ráhel skirted the edge of the forest to travel on better snow, she sought to make sense of the drama she’d witnessed:

The young man emerging suddenly from the trees to board the freight train. A body, for a moment airborne then plunged into a snowdrift. The man leaping after it.

She enjoyed resolving challenges. She’d become skilled at it in both her personal and professional life. In this unpredictable regime, the only world she’d known, the acts of observing, collecting and analysing reliable facts and then drawing conclusions, was all that stood between survival and a midnight pounding at the door by the Securitate.

“Challenges I enjoy,” she thought, “but not this one. Too many red lights.” But, like most Romanians, she’d learned that with dangers came opportunities.

She rested on the ridge and looked down into the valley dotted with large villas some painted some weathered wood. Ráhel needed to hear her mother’s reaction. She, who’d overcome so many challenges; she who had leverage some of them into assets. And she needed Ivan’s reaction. Ivan, who’d survived years in Gherla, mostly underground, in overcrowded darkness.

Trudy and Ivan had helped her make the right decision after she graduated from the Politehnica.

***

As a reward for having graduated summa cum laude in applied mathematics, the Party had offered Ráhel a teaching assistantship in her alma mater, the technical university whose mission was to boost innovation in a country with an underdeveloped rural economy.

But Ráhel had wanted more than a simple teaching job. Of the courses she’d taken, some had been useful. Those delivered by professors without technological experience had been disappointing. Students could learn more effectively from books. Ráhel wanted to test her mathematics on technology in action, she wanted a solid practical base for her teaching.

Post-War Romania was seeking desperately to expand its rail system. Ráhel wanted to learn how railbeds and rolling stock might be best designed to handle, safely and at speed, varying conditions. Any expansion of its rail system had to acknowledge that Romania was mountainous. Mathematics might predict what theoretical performance to expect from a locomotive. What it couldn’t do was tell engineers what would happen when day-to-day variables were factored in: the gauge of new rails, the quality of new steel, a laden freight car’s centre of gravity, the composition of the railbed, gradient, extreme weather.

Used to being wooed, never questioned, the Party members who controlled teaching appointments, had been outraged when Ráhel responded with her own proposal: part time with the Politehnica and part time with the state railway carrier. They issued her a summons.

“We’ll consult Ivan,” Trudy had said when the summons came. Consummately pragmatic as well as educated, she agreed with her daughter but feared the repercussions of challenging Party wishes.

Ivan listened. One of her dead father’s best friends and a survivor of a dreaded prison, Ivan had turned bad fortune into advantage. He’d never explained how. All he’d say was, ‘We intellectuals coped with incarceration better than the proletariat. We had inner resources.”

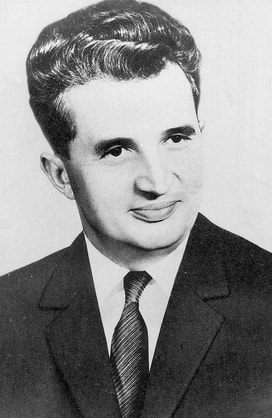

“Ráhel,” Ivan had advised in his quiet, confident way: “Let’s anticipate what the Committee needs. We’ll do their thinking for them.” He’d paused to summarise what Ráhel had told him. “Inform them, respectfully, what you’ve just said, that your proposal will help achieve Ceauşescu’s goals for Romania directly.” He summarised his protegee’s arguments on his fingers. “A speedier expansion of the rail network. Enormous savings on investment. A rapid increase in Romania’s capacity to bring in hard currency from exports.”

Quietly, Ivan had added, “A joint appointment will give you a legitimate opportunity to see what Romania’s state railway carrier is transporting and to where.”

All three sat silent. Each knew precisely what the implications were. Strategic intelligence. There was always a market for it.

***

The Party members at the Politehnica had listened to Ráhel, nodded at one another and arranged her dual appointment.

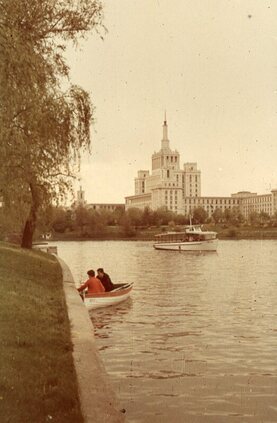

For more than a year now, she’d divided her time between marshalling yards and railway lines that criss-crossed her magnificent mountainous country, and Bucharest, the capital. When, occasionally, she and Trudy met Ivan, he never brought up his last remark. But they knew it was just a matter of time.

***

Ráhel continued to reflect as she slowly zig-zagged down towards the village on the edge of the river. Her father’s old cross-country skis weren’t built to handle slopes. Her gentle pace gave her time to reflect on how, under this regime, every citizen had a duty to report anything that might be construed as counter-revolutionary. The procedure was simple. A security file was kept on every citizen from school-age upwards, either in their place of education or work. Someone with something to report simply went to their “base”, the office where their file was kept and reported the incident to the Party member in charge. Unpleasant consequences followed for any breach of such duty, if discovered. So, students and teachers spied on one another, children on parents, neighbours on neighbours, workers on their fellows.

Fear was the Party’s handmaiden and the Party took pains to cultivate her.

What Ráhel had seen from her spot up on the mountainside, demanded reporting. But so had her first observation over two months ago. She’d been curious when she saw two men on skis observe the freight train from the cover of the pine trees. They’d watched it negotiate the tight curve on the mountainside.

She didn’t report what she’d seen. From the time her father died, she’d learned that it could be as dangerous to enter a report in her security file as not to. Entering a report brought attention. In a Communist state, a low profile was best.

Since that first unexpected observation, she’d returned to her own spot partly out of a legitimate interest in the way that such a curve impacted on the speed and safety of a long and heavy train but part, also, out of curiosity. Taking care to remain undetected, she’d watched the men repeat their observations at regular intervals. Then the younger man made his observations alone.

By accident, she’d spotted the younger man in the university faculty club dining room one day. Dressed like a Westerner, he was eating a lonely plate of mamaliga cu unt şi branza. No colleague would risk lunching with him because they would be obliged to report the conversation. The safest course was to avoid all contact with him. Reporting contact could bring suspicion on one’s self. Suspicion was enough to stall one’s career forever.

These thoughts plagued Ráhel as she undid her skis and entered the villa.

***

“There you are Macska!” Rahél’s anxiety subsided as soon as she heard the love in Trudy’s voice, saw it in her eyes. She still enjoyed the pet name pronounced as, motchko meaning kitten. “They’ve returned to Bucharest.” Trudy signalled silently. Ráhel knew the gesture meant that the caretakers were still in the villa, listening.

Ráhel felt a surge of affection and sorrow. Trudy’s handsome face was prematurely lined by hardship. Banished from her job as an art teacher in the Academy of Fine Arts when her husband had “died of complications”, she’d resorted to offering water colour classes privately. Ironically, her principal clients were the grossly unrefined wives of Party officials who sought the appearance of culture in an activity they imagined would give them an aura of respect. Their paying Trudy for classes contravened a Party decree against private enterprise. That they could ignore it was one of the many anomalies within Communist Romania. Infringements could be ignored, at least until a self-serving denunciation might be conveniently made. But denunciations could go both ways.

This weekend, with the condescension of those unused to legitimate authority, the wife of a Central Committee member had summoned Trudy to a villa in Sinaia. After 1949, villas appropriated from the previously wealthy or hard-working were commandeered for the use of senior Party members. The wife in question had invited a clutch of friends who, like her, had nothing better to do than pretend to be aspiring artists.

Ráhel had been allowed to accompany her mother but had excused herself from their coarseness and idle gossip. Trudy was obliged to tolerate them, but she listened for any detail that might serve her. Within Ceauşescu’s stifling regime, customers existed for fragments, be they gossip or fact.

***

Trudy put on hat, coat and scarf. Comfortable together, mother and daughter walked arm-in-arm like a pair of school-girls. Sunshine reflected off the fresh snow and turned the valley with its ski-slope, its wooden villas and mature trees into a visual paradise, alas, no longer genuine.

“The wives became bored with the patience that water colours demand.” Trudy explained. “When they ran out of gossip, they summoned the drivers of their husbands’ limousines, drew the privacy curtains to heighten their importance, and scurried back to the city.”

Ráhel was only half-listening.

“You’re worried, Macska.”

Ráhel and Trudy had no secrets. In the quiet valley, they walked and talked, making sure to keep their faces square into the wind so that their conversation could not be captured by a device other than their own ears.

***

Ráhel told her mother all she had seen. Both were silent for a while.

Trudy longed for her husband’s presence, more now, than at any time in the past few years.

Romanians, from ethnic Romanian stock or from the Hungarian minority like Trudy, knew the value of talking things over with a trusted friend. An incautious remark might bring disaster. Her life had changed the day after her husband had had an altercation with a senior Party official. He’d been an executive with the government news media. The day after the altercation, he’d left for work as usual. Mid-morning, a stony-faced official messenger had brought Trudy, painting in her studio, a chilling note. She knew its words by heart:

“At precisely 0935 hours, our Comrade, your husband, had a painful attack. He was taken to hospital. There he was diagnosed with appendicitis. An operation was advised. Complications occurred. While on the operating table, Our Comrade, your husband, died.”

***

From that day, mother and daughter had become more, they’d become confidants. As intimates, they lived in the large single room where once a doctor and his family had dined. That was before the Communists took possession of the doctor’s home, assessed it’s potential and assigned a family to each of the seven rooms. For the seven families, there was a shared bathroom on the first floor and a toilet on the ground floor.

Trudy had sought Ivan’s advice on how to proceed after she was driven out of the Academy. Ivan, like Trudy and her husband and thousands of others, had been resettled from Timisoara to Bucharest. Resettlement was deemed necessary to satisfy the need that the first communist prime minister of the People’s Republic of Romania felt to alter Timisoara’s ethnic balance. He moved many Hungarians out, many Romanians in.

Ivan’s advice to Trudy had been that she offer private art classes. The authorities, he guessed, would turn a blind eye because it relieved them of the task of demoting an artist of her renown to a menial task within the Academy. Real artists would be faithful to her ability to teach privately and the now-rich wives of Party leaders would gain imaginary prestige by letting it be known to their friends that a famous painter was their personal teacher.

Ivan explained to Trudy that the risk of being denounced for engaging in an unauthorised entrepreneurial enterprise would be offset by the opportunity to glean useful information. Information, no matter how apparently insignificant, might prove useful not only for her protection but also to unspecified “others” with whom he said he was, “in touch”.

***

Ráhel broke Trudy’s reverie. “We must speak to Ivan.” Trudy nodded. If found, the dead body would instigate an investigation. Ráhel would be in danger. And so would she, once again.