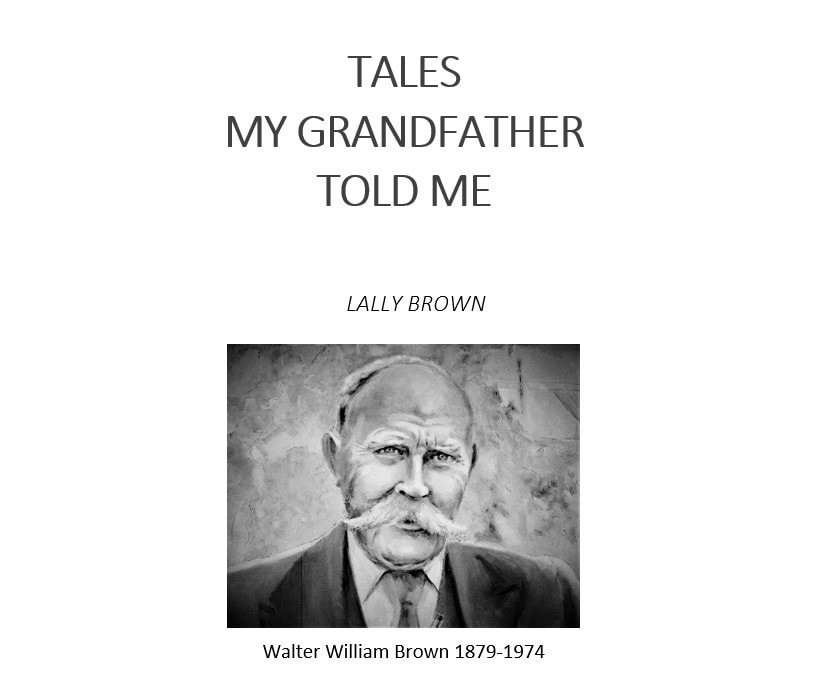

My grandfather was larger than life in every way. He was a straight-talking, no-nonsense, forthright and stubborn bull of a man. Hewn from granite and polished by his experiences into a strong, self-willed eccentric. We grandchildren adored him. He kept us enthralled and entertained for hours with tales of his adventures.

When the family gathered together at Christmas he would settle himself into an armchair with his grandchildren at his feet. We would fidget with barely concealed impatience for the stories of his life to begin. But first he would fill his old pipe. Pulling a generous pinch of his own home-grown tobacco from a battered tin he kept in his waistcoat pocket, he would carefully press a wad of the dry, tufty, brown leaf into the bowl of his pipe while we watched and waited.

I can still smell that heady smoke as it rose lazily into the air. He’d grip the pipe between his teeth and puff in quiet satisfaction. When he was ready to start his tales he’d gaze down at us, his grandchildren, his blue eyes twinkling, his bushy handlebar moustache twitching, and he’d smile.

“Tell us about the Klondike gold rush!” My brother would demand.

“No, I want the Singapore mutiny!” My sister would cry.

I would stay mute. I was in awe of this giant of a man and just adored all his stories.

Grandfather was born in a lodge on the Great Windsor Park estate in 1879. My great grandfather was a forester working for Queen Victoria. Great grandfather’s name was John Brown and I have often been asked if he was the notorious John Brown the Queen was so fond of in her later life. But no, he was not. It is possible they were related but my great grandfather was twenty years younger than the Scottish gillie who was so beloved by the Queen.

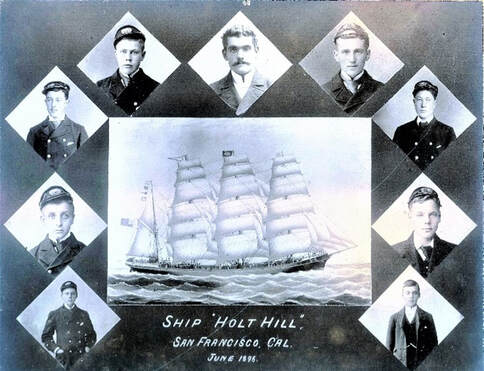

At fifteen grandfather was ready for excitement and adventure. He’d had enough of peaceful, rural living on the Royal estate in Windsor and he ached to see the world, so his parents paid for him to be taken as a cabin boy on a four-masted sailing ship called the “Holt Hill”.

His first, and as it turned out his only, voyage on the “Holt Hill” lasted over twelve months. It sailed from Liverpool in 1895 ultimately destined for the port of San Francisco. Grandfather was one of a crew of forty and apparently he worked hard and willingly.

When the family gathered together at Christmas he would settle himself into an armchair with his grandchildren at his feet. We would fidget with barely concealed impatience for the stories of his life to begin. But first he would fill his old pipe. Pulling a generous pinch of his own home-grown tobacco from a battered tin he kept in his waistcoat pocket, he would carefully press a wad of the dry, tufty, brown leaf into the bowl of his pipe while we watched and waited.

I can still smell that heady smoke as it rose lazily into the air. He’d grip the pipe between his teeth and puff in quiet satisfaction. When he was ready to start his tales he’d gaze down at us, his grandchildren, his blue eyes twinkling, his bushy handlebar moustache twitching, and he’d smile.

“Tell us about the Klondike gold rush!” My brother would demand.

“No, I want the Singapore mutiny!” My sister would cry.

I would stay mute. I was in awe of this giant of a man and just adored all his stories.

Grandfather was born in a lodge on the Great Windsor Park estate in 1879. My great grandfather was a forester working for Queen Victoria. Great grandfather’s name was John Brown and I have often been asked if he was the notorious John Brown the Queen was so fond of in her later life. But no, he was not. It is possible they were related but my great grandfather was twenty years younger than the Scottish gillie who was so beloved by the Queen.

At fifteen grandfather was ready for excitement and adventure. He’d had enough of peaceful, rural living on the Royal estate in Windsor and he ached to see the world, so his parents paid for him to be taken as a cabin boy on a four-masted sailing ship called the “Holt Hill”.

His first, and as it turned out his only, voyage on the “Holt Hill” lasted over twelve months. It sailed from Liverpool in 1895 ultimately destined for the port of San Francisco. Grandfather was one of a crew of forty and apparently he worked hard and willingly.

Grandfather top left cabin boy on “Holt Hill” 1896

When the ship finally arrived in San Francisco the city was buzzing with rumours that gold had been found up in the Klondike, two thousand miles away. It was 1896 and the beginning of the infamous Klondike Gold Rush which was to last three years. During that period over 100,000 eager prospectors set off for the Klondike with the majority leaving from San Francisco. Young men desperate to make a fortune but totally unprepared and ill-equipped for the hazardous conditions they would encounter. Only 30,000 arrived at the gold fields and of those it is estimated that a mere 4,000 found any gold. Thousands died along the way, most from typhoid.

The crew of “Holt Hill” heard the rumours, the stories of get-rich-quick and fabulous wealth there for the taking, and a group of them were dazzled by the stories and whispered together about jumping ship. They asked grandfather to join them. He told us he was very tempted, but he was only a lad and he was very certain his parents would heartily disapprove. The Captain heard the whispers and forbade any crew members to abandon “Holt Hill”. Grandfather felt he had no choice but to remain faithful to his Captain. But almost half the crew had no such loyalty and the night before “Holt Hill” was due to sail they managed to slip away into the darkness. Grandfather never knew what became of them.

The remaining crew struggled to sail the “Holt Hill” back to Liverpool and grandfather found himself doing work way beyond his experience and capabilities. Climbing the mast to haul in sails was not a normal part of a cabin boy’s duties. Stormy weather hit them as they rounded Cape Horn and an inexperienced lad, a good friend, was ordered up the mast to secure the rigging. Grandfather was on deck and watched in horror as his friend lost his grip and fell off the rigging into the storm tossed waters of the Cape.

“It was impossible for us to do anything to save him.” Grandfather would pause, shake his head and sigh.

“That’s the moment I decided a life at sea was not for me!” said grandfather.

But his parents had contracted with the company and there seemed to be no way out. However grandfather had a plan.

“They had one strict rule” he told us “they could not employ anyone who was colour blind. After all you don’t want a sailor who confuses red and green on board a sailing ship.”

So he told them he had trouble distinguishing different colours.

“Of course they didn’t believe me so they sent me for a test…” blue eyes twinkling he continued “…a table was laid out with lots of different coloured strands of wool, they gave me a red piece and told me to pick up any wool that matched. I had a wonderful time.”

He would guffaw wickedly when he told us this, pungent blue smoke billowing from the pipe clenched between his teeth.

So he was dismissed, officially classed as colour blind, and told he could never join the navy or go to sea again. In his defence his confusion with colour was partially true, he never could tell parsnips from swedes.

* * *

In frustration his parents decided he needed a profession, one that would enable him to gain employment easily and earn plenty of money. So he was enrolled into an apprenticeship with a cabinet maker to learn the skill of carpentry. He had, according to the family, a natural talent, and when he qualified as a Journeyman Carpenter his customers included many of the gentry who lived in the exclusive properties around Ascot. Their panelled halls and mahogany cabinets all made by my grandfather. Through his friendships made in Ascot, grandfather became a staunch supporter of the horse racing during Royal Ascot Week. He made an annual pilgrimage to the racecourse for the Gold Cup and he was still attending the year he died.

But as a young man he yearned for adventure and in 1900 he made the decision to join the Royal Engineers where his qualifications as carpenter and joiner entitled him to non-commissioned officer rank. Army life suited him and he remained with them for twenty-six years. He was initially assigned to Inkerman Barracks in Woking and one of his first duties was participating in the arrangements for Queen Victoria’s funeral. He was honoured to be invited to be a part of the ceremony during her funeral in London.

Four years later found him posted to Sierra Leone for eighteen months. Two weeks before he left he married my grandmother in a splendid ceremony in Portsmouth. Their first child, my aunt, was born while he was away.

Grandfather always seemed a little reluctant to talk about his months in Sierra Leone, and in later years I understood why. It was not a period of history in which the British could be proud. For many years this area of West Africa had been a safe haven for escaping slaves, freed and protected by the British from slave ships that still plied their evil trade along the coast of Africa. A colony of black loyalists and liberated Africans flourished here, their main town becoming known, very appropriately, as Freetown.

An amicable arrangement with surrounding tribal Chiefs and Kings existed and the freed slaves and their descendants became known collectively as Creoles and had an important voice in local affairs. However in 1895 the British decided to create a ‘Protectorate’ around Freetown, arbitrarily creating borders along rivers, valleys and forests taking no notice of territorial rights of Chiefs or Kings. This high-handed attitude angered the Chiefs and there was, not surprisingly, an armed rebellion with the British inflicting some pretty nasty punishment on ‘rebels’ they caught.

The uprising was eventually quelled in 1898, six years before my grandfather’s tour of duty, but the comfortable co-existence between the colonial British, the Chiefs, Kings and Creoles had been lost.

In order to escape the daily pressures of his army life in Sierra Leone, grandfather would disappear into the dense tropical rainforest and collect butterflies, which he mounted, pinned, into a glass case. Beautiful though the butterflies were, I couldn’t look at those glass cases without shuddering slightly, even at that tender age the thought of netting and piercing such exquisite creatures onto a board was not something that appealed to me.

Grandfather would always pause at this part of his story. More for effect than needing to refill his pipe. He knew the next tale was our favourite. My brother would wriggle with impatience as the pipe was refilled, the cup of tea sipped and the Christmas cake nibbled. Grandfather certainly knew how to hold the attention of his adoring audience.

Grandmother Brown with my aunt and father 1910

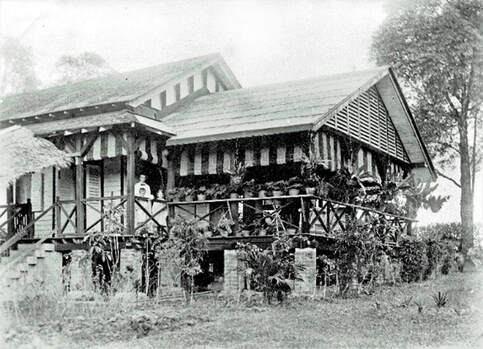

It was September 1913 when grandfather was posted as Warrant Officer Class 1, Serjeant Major, to Singapore. This time the family accompanied him and were housed in a very comfortable bungalow in the European residential area of Tanglin, an outlying district of Singapore. As Clerk of Works with the Royal Engineers grandfather’s life was one of colonial comfort and privilege with servants, tennis, picnics, and many social events.

Bungalow at Tanglin, Singapore 1913-1916

Grandmother, aunt and my father Singapore 1914

Tennis team Singapore 1914

Grandfather and Grandmother back row centre right

Grandfather and Grandmother back row centre right

The family was living in Singapore when World War I was declared on July 28th 1914. Initially it had little effect on the community but in November 1914 when the German cruiser SMS ‘Emden’ was destroyed, many of her surviving sailors and naval officers were imprisoned on Dempsey Hill at Tanglin Barracks in Singapore. In total the barracks held over three hundred German ‘internees’ and grandfather was one of the officers in charge of their security and accommodation. Grandfather said they were in general an easy-going bunch and a friendly rapport developed between the prisoners and the British officers supervising their internment.

On a daily basis the prisoners were guarded by the 5th Light Infantry, all Indian and all of one religion and caste. The Indians were trained regular soldiers but over several months they had become disillusioned with their British Commander, who was unpopular even with his fellow officers. Dissatisfaction rippled through the Indian ranks and their British Senior Officers reported them as ‘unreliable and undisciplined’ but the Commanding Officer seemed indifferent.

Matters took a dramatic turn when incorrect rumours began to circulate among the Indian soldiers (the sepoys) that the 5th Light Infantry was soon to be posted, not to Hong Kong as they had expected, but to Europe to fight Turkish fellow Muslims.

This rumour served to fuel their feelings of discontent, and on the 14th February 1915 over half the Indians in the 5th Light Infantry mutinied. The infamous ‘Sepoy Mutiny of Singapore’ began. On that day Singapore was celebrating the Chinese New Year and most of the British Army personnel, approximately two hundred and fifty, were absent enjoying the holiday. As a consequence the British army barracks was almost deserted. Grandfather was one of the few officers remaining and he was playing golf with friends at Tanglin that afternoon.

The only soldiers on site were a small detail of the 36th Sikhs who were passing through on their way to Hong Kong. They were relaxing in the barrack room at Tanglin but had no ammunition. Others in the vicinity were Volunteer forces, including fifty men of the Malay States Volunteer Rifles.

The mutineers were in the Native Infantry Barracks four miles from Tanglin. They broke into the magazine and helped themselves to ammunition. Half the Indian troops and one hundred men of the Malay State Guides (four hundred men in total) advanced on the building holding the Germans at Tanglin Barracks. Grandfather said that some of the German officers, in particular one Captain Lauterbach, had been instrumental in inciting the Indians to mutiny.

The mutineers went berserk and shot on sight any person they believed to be British. They arrived at the prison unhindered, shot all the Volunteers and British Officers on guard and threw open the gates offering rifles and ammunition to the German prisoners. A few escaped but the majority refused to move and also refused to take up arms.

After releasing the prisoners the mob went on the rampage, shooting and killing any white person they met. They headed for the Tanglin Barracks intent on killing the Commanding Officer they believed had changed their orders and was sending them to Europe to fight fellow Muslims.

The first grandfather knew of the trouble was when one of the Volunteer soldiers from the prison came running across the golf course towards him, blood pouring from a wound in his throat where he’d been shot.

Grandfather raced to the bungalow shouting to my grandmother to get the family out immediately and head for the docks. Then without a thought he turned, and ran, unarmed and still dressed for golf, up to the prison.

The gates were open as he made his cautious way inside. The German prisoners who knew him well, saw him, and pulled him inside, stripped off his clothes and dressed him in prisoner uniform.

“They’ll kill you if they find you” he was warned “they’re murdering any British officer they can find.”

He was spotted by one of the mutineers who recognised him. But the Germans surrounded him in a protective circle and pointing to his prison clothes insisted he was a prisoner like themselves who merely resembled the officer they knew. They saved my grandfather’s life.

Meanwhile my Grandmother had fled with the children to the docks. She was half dressed.

“Only one stocking and no shoes” remembered my father as he added to the story.

When they reached the docks they found a group of other British army wives with their children. All were put on a launch and taken out for safety to a Russian ship in the harbour. The ship was an auxiliary cruiser which in peacetime connected Japan with the Siberian Railway. They were welcomed on board and sat huddled together on deck. Only one Officer spoke English but they were kind in every way possible. Mattresses were laid out on deck and tinned mutton soup handed round.

For several days my grandmother and her friends remained on the Russian ship. No clothes, no proper washing facilities, soup for nourishment and whooping cough going round the children.

The initial crisis lasted seven days before it was brought under control with the assistance of Russian, French and Japanese naval forces. But it took several more days for the authorities to round up all the mutineers.

More than two hundred of the Indian mutineers were tried by court-martial. Forty-seven were publicly executed by firing squad, witnessed by a crowd of over fifteen thousand who gathered on the hillside above the site. Sixty-four were transported for life, and seventy-three given terms of imprisonment from seven to twenty years. The British Commanding Officer was heavily criticised as being ‘ineffective’ and contributing to the unrest. He was reprimanded and retired from the Army.

My grandmother was in the first group to be allowed ashore and back into her home at Tanglin Barracks. She was lucky, the following day fire broke out on the Russian ship which had given her safe shelter and the remaining forty-two women and fifteen children still on board had to be quickly transferred to another Russian ship, the Orel, which had arrived to help quell the mutiny.

Forty-four British officers, soldiers and civilians, three Chinese and two Malay civilians were killed during the uprising. One British women also died but her death was considered to have been accidental.

Grandfather was at great pains to emphasize that many of the 5th Light Infantry had remained loyal and although fifteen German prisoners did escape the majority remained inside, even though the gates were open. He was always acutely aware that he owed his life to those prisoners who had so selflessly protected him.

* * *

His treasure trove of tales seemed endless, and grandfather would continue with his stories well into the night and most of Boxing Day. Christmas presents took second place to grandfather’s exciting adventures.

We listened intently as he told of his six years in Gibraltar and later, after retiring from the army, of his work with the RAF and Air Ministry when he was sent to Amman in Transjordan to put in an airstrip for the pioneer aviator Sir Alan Cobham, who was attempting to fly his little biplane from England to Australia.

He spoke of meeting Lawrence of Arabia in the Middle East, the British Intelligence Army Officer who became a legend after his World War I exploits with Arab rebel allies. We were enthralled by the stories Lawrence told him, and saddened to hear of Lawrence’s eventual disillusionment with the British. Grandfather’s warmest memory of T.E. Lawrence was playing chess with him on board ship as they travelled back to England together.

Grandfather also boasted of his several brushes with authority, of the stinging letters he regularly wrote to superiors in the British Army when he believed they were “totally incapable of understanding what was happening on the ground!”

His greatest triumph came when he sued the Inland Revenue over some taxation law that had left him seething with the injustice of it. He took them to the High Court in London, conducting his own defence and giving a stunning performance, he was 90 at the time!

* * *

Grandfather outlived his wife, daughter and two daughters-in-law, and lived alone in the bungalow he’d built himself until his death at 94. I like to think he would have thoroughly approved of the manner of his own passing, which happened in a unique, freak accident.

As a young man grandfather had bought himself a bicycle and he encouraged us all to enjoy cycling “For its enormous health benefits.” In truth he’d bought the bike in protest when the government put fuel tax on transport and bus fares were increased to compensate. Grandfather vowed never use public transport again and his trusty bike became his preferred mode of transport. There were occasions when the distance was too great and he needed to travel by car, so my father or my uncle would step in to oblige. But at 94 he still used his high-step ancient bike to get him into town for his weekly shop and visit to the bank. It was an easy ride. A long straight road with a gentle downhill final lap followed by a sharp left turn into the market place. He’d done this ride every week for over forty years. He prided himself in getting up speed on the downhill stretch so that he could barrel the sharp left and glide to a halt beside the market.

The week he died a construction firm was busily putting up scaffolding around the office building on the corner by the market. One rogue scaffold pole was waiting to be placed, hanging three feet above ground and protruding into the road. Grandfather was oblivious. As usual he took the bend at speed, only to be catapulted into the air as his bike slammed into the pole. He broke an ankle but his spirit was undaunted. As the ambulance arrived he could be heard angrily berating the construction team for their incompetence. However, within days of the accident he developed pneumonia and died within a week of being admitted to hospital.

Grandfather was a force of nature, a unique eccentric and a truly entertaining teller of tales, and I am incredibly proud to be his granddaughter.

* * *