Early Rumblings by Shane Joseph

My earliest memory of my youngest brother, Mario, was of my precariously pregnant Mum emerging from the bathroom, sweat pouring down her face, holding her hips in pain and announcing that her water had broken.

“But it’s Poson Poya” (the full moon holiday in June in Ceylon), said my Dad, flustered and slightly inebriated from the “pint” he had been nursing with my bachelor Uncle Anton who lived with us. “There is not even a taxi available at this time of night. Why is this child coming so early? You aren’t due for two more weeks.”

But some form of transport came to the rescue, from a neighbour or a relative, I can’t recall now. Dad was years away from getting his promotion to office manager and receiving a company car as a perk. As Mum was driven away, I went to bed being promised that she would return in a few days with a baby.

The next day, Dad took me to Suleiman’s Maternity Home in Armour Street, Colombo, an oasis of calm, order, and hospital antiseptic odour, situated in the middle of a cacophonous and dirty commercial neighbourhood. But Dad swore by Suleiman’s, where me and my brother Dane had been born without a hitch, and without too much expense.

Mario was born around 5 p.m., and I recall asking Dad if all babies were born at this time, because the last time we had been at Suleiman’s, three years ago, Dane was born at the same time. Dad simply told me “No.” He went onto say that I was born at 3 a.m. – suggesting, perhaps, that I was a more difficult child than my two brothers were ever going to be.

***

Mario was the skinniest of all of us – weighing around six and half pounds (the rest of us all clocked in over seven pounds at birth). But he generated a roar to wake the dead. In fact, he developed that voice to the point that when he was about two years old, he screamed so loud he perforated his ear drum.

My family has a knack for using rhyming names. My paternal grandmother had named her first three children Carmen, Sherman and Herman, in that order, before confusion arose when each was summoned: Carmen would come when Sherman was called and Sherman would come when Herman was called, or so the story goes. Therefore, the remaining siblings were called by names that didn’t rhyme at all – Leonie and Yvonne. Similarly, in my family, my parents had gotten off to a good start with Shane and Dane. Then Dad pulled himself up short and said, “No more rhyming names! Please!”

Everyone wanted a say in what to name this third child, and the most persuasive, Aunty Yvonne, advanced the name Kevin, a rare name in post-colonial Ceylon at the time, just like mine had been. (I found out later I was named after a cowboy gunslinger). As my Mum insisted also on a saint’s name, Mario was added as the middle name: Kevin Mario Joseph. I still have not encountered a Saint Mario in any Christian literature, but Mario was to be the middle name, even though middle names were never used much anyway. Dad grumbled, “Why the heck do you need another saint’s name when we are all Josephs?” But Mum was adamant and won this argument.

On the way home from the christening, I sat in the ancient Morris Minor taxi with Mum and Dad, my brother Dane, and the newly named baby on Mum’s lap. A billboard flashed by and Mum suddenly yelled over the taxi’s grinding roar. “My God! We have named our child after a shoe polish!”

She was right. A new brand of leather shoe polish had entered the market, heralded by a big promotion campaign. As we didn’t have TV then, billboards screamed the loudest. And Mum had just seen an advertisement for Kevin Shoe Polish go by.

“No bloody way am I going to call my son after a shoe polish,” Mum exclaimed.

“Too late,” said Dad from the front passenger seat. “We signed the church baptismal register.”

“We must change it!”

“You go and change it. I am not kowtowing to that bloody parish priest who thinks he’s the cat’s whiskers and looks at us buggers as if we’ve all come from hell!”

Mum beamed. “I know. We will call him Mario!”

My family has a knack for using rhyming names. My paternal grandmother had named her first three children Carmen, Sherman and Herman, in that order, before confusion arose when each was summoned: Carmen would come when Sherman was called and Sherman would come when Herman was called, or so the story goes. Therefore, the remaining siblings were called by names that didn’t rhyme at all – Leonie and Yvonne. Similarly, in my family, my parents had gotten off to a good start with Shane and Dane. Then Dad pulled himself up short and said, “No more rhyming names! Please!”

Everyone wanted a say in what to name this third child, and the most persuasive, Aunty Yvonne, advanced the name Kevin, a rare name in post-colonial Ceylon at the time, just like mine had been. (I found out later I was named after a cowboy gunslinger). As my Mum insisted also on a saint’s name, Mario was added as the middle name: Kevin Mario Joseph. I still have not encountered a Saint Mario in any Christian literature, but Mario was to be the middle name, even though middle names were never used much anyway. Dad grumbled, “Why the heck do you need another saint’s name when we are all Josephs?” But Mum was adamant and won this argument.

On the way home from the christening, I sat in the ancient Morris Minor taxi with Mum and Dad, my brother Dane, and the newly named baby on Mum’s lap. A billboard flashed by and Mum suddenly yelled over the taxi’s grinding roar. “My God! We have named our child after a shoe polish!”

She was right. A new brand of leather shoe polish had entered the market, heralded by a big promotion campaign. As we didn’t have TV then, billboards screamed the loudest. And Mum had just seen an advertisement for Kevin Shoe Polish go by.

“No bloody way am I going to call my son after a shoe polish,” Mum exclaimed.

“Too late,” said Dad from the front passenger seat. “We signed the church baptismal register.”

“We must change it!”

“You go and change it. I am not kowtowing to that bloody parish priest who thinks he’s the cat’s whiskers and looks at us buggers as if we’ve all come from hell!”

Mum beamed. “I know. We will call him Mario!”

***

Mario grew up to be a scrappy kid. He had it tough from the start, with two older brothers, ages 10 and three, who didn’t give him much breathing room. And he always got into scrapes.

Once, when he was a year and bit old, he clobbered Dane and ran, tripped on the polished cement floor, and fell, face forwards onto a sharp-edged stool, cutting his eyebrow and requiring stitches. A few years later he made sure to balance off his appearance by having another accident and cutting his other eyebrow. On another occasion, again fleeing from Dane, he ran into the glass French louver windows, braking at the last minute, but not before he got impaled on the glass blades. Extricating himself, he bragged about his scarred chest, and often lifting his shirt thereafter to show off his war wounds to interested spectators.

And of course, he used his mighty voice to great advantage. We often experienced power cuts in those days and the ceiling fans went silent and motionless, ushering in mosquitoes to bite us relentlessly on humid tropical nights. Of course, Mario never slept during these power-less occasions and kept us all awake with his whining. So, Dad would lay him down on a sheet in the living room under the inert ceiling fan and use a newspaper to manually fan the little guy to sleep. From my bedroom, I could see Dad’s hand strokes, with the makeshift newspaper fan, start to slow down as he began to drift into slumber from his own fanning. Suddenly Dad (and all of us) would jolt awake when this toddler sat up on his sheet and screamed “FAN ME!”

This operation would be repeated several times until I fell asleep myself, or the electricity came on at some point in the night to get the ceiling fan in motion, and Dad could give his cramped hand, and his body, a rest from this highly-strung and demanding kid lying beside him.

Given the age difference between me and my younger siblings (I was seven years older than Dane, 10 years older than Mario and 12 years older than Tania) I didn’t get to hang around them much other than to act as an extra caregiver. I remember when I took Dane to his first day of school, he just walked through the gate of his Montessori schoolhouse, waved at me and disappeared inside. Dane was a placid kid, and still is. I didn’t have the same luck with Mario when we repeated the same operation three years later. My little brother, upon entering the school gates and realizing that his independence was about to be lost forever within the halls of academia, clutched his throat and collapsed on the dusty ground, ruining his well-laundered clothes. From there he proceeded to wail at the top of his voice—shattered ear-drum, be damned! — and roll all over the school driveway. Teachers and pupils rushed out to see this little maniac “doing the devil dance,” as Mum would say. No amount of pleading, cajoling, or threatening would get him to rise and enter the school. Defeated, I took this muddy and tousled kid back home and said to Mum, “Tomorrow, you take him!”

The next day, Dad took him. Apparently, a similar dramatic scene ensued, but my dad was a strict disciplinarian. I think a few “thundering slaps,” as my Mum called them, were administered, and Mario finally entered school.

Being the eldest, it was my duty to take my brothers to school when they left Montessori and entered St. Benedict’ College where I was studying. I wanted to kill these little buggers when they followed me there. Why?

Because I played cricket after school, both in the Under 14 team and later in the Under 16 team, and I had to haul these two guys with me to the playground and sit them down while I practiced with my mates. I was obliged to keep my eyes on my little brothers as much as I kept my eyes open for the bowler charging down on me, or the ball hurling through the air at my face. This was hard and distracting work. Whenever I looked up from the game, one or both of my brothers had vanished. And there was I, excusing myself from my dismayed team-mates and our frowning coach, and running to find the disappeared ones. But I felt sorry for my brothers when we would head to the bus stand for the long ride home after my cricket practice. It would be a long day for them – up at 6 a.m. and returning home with me at almost 7 p.m. Despite being entertained by male and female coolies (the females, by caste dictates, could only drape a loose saree over their bare breasts, treating bystanders to a “free show”) who descended on the bus stand from the nearby tavern, reeking of toddy and sweat, and watching them spit red streams of betel about them as they squatted on their haunches and spewed a colourful language, my brothers would be fast asleep by the time we arrived at our home stop. But they never complained because they always wanted to do what their “Big Brother” did, and do it better.

Relief came when I switched over to St. Peter’s College to do my A’ levels. Dane and Mario switched with me, because Dad insisted that Big Brother still had to look after them. Besides, they also got the opportunity to switch over to the English medium at St. Peter’s, which I decided was worth the sacrifice of having these two pests hang onto my shirt sleeves – they would have more opportunities open to them by studying in English. But I made a deal with them and with my parents: with St. Peter’s being closer to home than St. Benedict’s and needing only one bus instead of two, my brothers were going to travel home alone when I put them on the bus after the final bell, so that I would be free to pursue my extra-curricular activities and return later in the evening. To my relief, everyone agreed.

Those double-decker buses were not oases of comfort. Discards from London Transport in the UK and sent at bargain prices to the colonies where their lives would be extended on narrow and rutted roads, they were often packed to the footboards with passengers, swinging wildly around bends and taking strips off pedestrians who dared to step off the sidewalk, if sidewalks existed. But my brothers found the belching double-decker bus the perfect nest to rest from their labours at school, more than one would expect.

I knew the transition wasn’t going to be easy. Many are the sightings of two little Burgher boys running from the Welikada junction where the bus terminated, back to our home down 4th Lane, Nawala, a distance of about two miles. Why? Because these two guys would fall asleep in the bus and get carried all the way to the terminal, only to be woken up by the conductor cleaning up for the return journey. After this “over-carrying” had gone on far too many times, Mum finally decided to mount a daily watch at the bus stand opposite our lane, waiting to catch sight of two sleepy heads inside the #198 bus coming from Dehiwala via St. Peter’s College, Bambalapitiya, and should they not disembark, halt the bus by standing in the middle of the road, to retrieve her children before they nodded off to Welikada again.

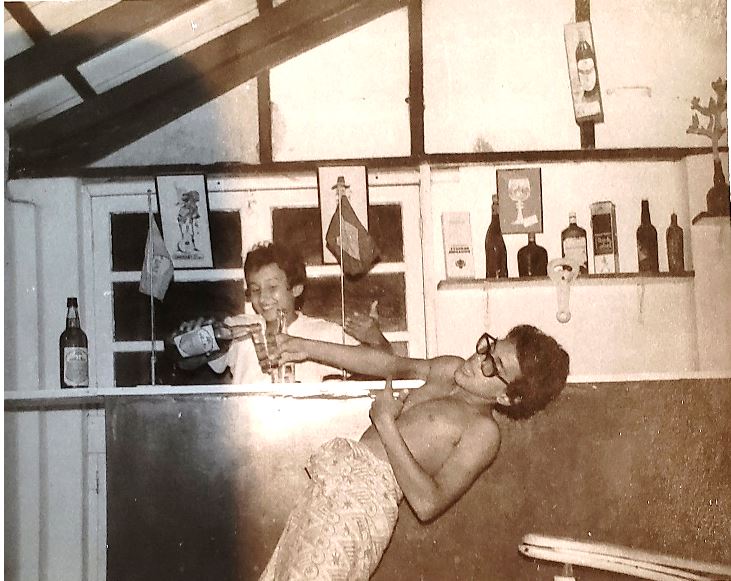

Childhood disappears far too quickly. My remaining memories of my siblings were when we went to Dad’s office bungalow situated between a lagoon and the ocean in Bentota, years later, after my father received his promotion and began enjoying management “perks.” I remember the night Mario and Dane put on an entertainment for us, acting as two drunks in a bar. From the photo, you will see that they put on a convincing show. Later, I found out that the bottle contained a bit of the “real stuff” to get them into character.

Once, when he was a year and bit old, he clobbered Dane and ran, tripped on the polished cement floor, and fell, face forwards onto a sharp-edged stool, cutting his eyebrow and requiring stitches. A few years later he made sure to balance off his appearance by having another accident and cutting his other eyebrow. On another occasion, again fleeing from Dane, he ran into the glass French louver windows, braking at the last minute, but not before he got impaled on the glass blades. Extricating himself, he bragged about his scarred chest, and often lifting his shirt thereafter to show off his war wounds to interested spectators.

And of course, he used his mighty voice to great advantage. We often experienced power cuts in those days and the ceiling fans went silent and motionless, ushering in mosquitoes to bite us relentlessly on humid tropical nights. Of course, Mario never slept during these power-less occasions and kept us all awake with his whining. So, Dad would lay him down on a sheet in the living room under the inert ceiling fan and use a newspaper to manually fan the little guy to sleep. From my bedroom, I could see Dad’s hand strokes, with the makeshift newspaper fan, start to slow down as he began to drift into slumber from his own fanning. Suddenly Dad (and all of us) would jolt awake when this toddler sat up on his sheet and screamed “FAN ME!”

This operation would be repeated several times until I fell asleep myself, or the electricity came on at some point in the night to get the ceiling fan in motion, and Dad could give his cramped hand, and his body, a rest from this highly-strung and demanding kid lying beside him.

Given the age difference between me and my younger siblings (I was seven years older than Dane, 10 years older than Mario and 12 years older than Tania) I didn’t get to hang around them much other than to act as an extra caregiver. I remember when I took Dane to his first day of school, he just walked through the gate of his Montessori schoolhouse, waved at me and disappeared inside. Dane was a placid kid, and still is. I didn’t have the same luck with Mario when we repeated the same operation three years later. My little brother, upon entering the school gates and realizing that his independence was about to be lost forever within the halls of academia, clutched his throat and collapsed on the dusty ground, ruining his well-laundered clothes. From there he proceeded to wail at the top of his voice—shattered ear-drum, be damned! — and roll all over the school driveway. Teachers and pupils rushed out to see this little maniac “doing the devil dance,” as Mum would say. No amount of pleading, cajoling, or threatening would get him to rise and enter the school. Defeated, I took this muddy and tousled kid back home and said to Mum, “Tomorrow, you take him!”

The next day, Dad took him. Apparently, a similar dramatic scene ensued, but my dad was a strict disciplinarian. I think a few “thundering slaps,” as my Mum called them, were administered, and Mario finally entered school.

Being the eldest, it was my duty to take my brothers to school when they left Montessori and entered St. Benedict’ College where I was studying. I wanted to kill these little buggers when they followed me there. Why?

Because I played cricket after school, both in the Under 14 team and later in the Under 16 team, and I had to haul these two guys with me to the playground and sit them down while I practiced with my mates. I was obliged to keep my eyes on my little brothers as much as I kept my eyes open for the bowler charging down on me, or the ball hurling through the air at my face. This was hard and distracting work. Whenever I looked up from the game, one or both of my brothers had vanished. And there was I, excusing myself from my dismayed team-mates and our frowning coach, and running to find the disappeared ones. But I felt sorry for my brothers when we would head to the bus stand for the long ride home after my cricket practice. It would be a long day for them – up at 6 a.m. and returning home with me at almost 7 p.m. Despite being entertained by male and female coolies (the females, by caste dictates, could only drape a loose saree over their bare breasts, treating bystanders to a “free show”) who descended on the bus stand from the nearby tavern, reeking of toddy and sweat, and watching them spit red streams of betel about them as they squatted on their haunches and spewed a colourful language, my brothers would be fast asleep by the time we arrived at our home stop. But they never complained because they always wanted to do what their “Big Brother” did, and do it better.

Relief came when I switched over to St. Peter’s College to do my A’ levels. Dane and Mario switched with me, because Dad insisted that Big Brother still had to look after them. Besides, they also got the opportunity to switch over to the English medium at St. Peter’s, which I decided was worth the sacrifice of having these two pests hang onto my shirt sleeves – they would have more opportunities open to them by studying in English. But I made a deal with them and with my parents: with St. Peter’s being closer to home than St. Benedict’s and needing only one bus instead of two, my brothers were going to travel home alone when I put them on the bus after the final bell, so that I would be free to pursue my extra-curricular activities and return later in the evening. To my relief, everyone agreed.

Those double-decker buses were not oases of comfort. Discards from London Transport in the UK and sent at bargain prices to the colonies where their lives would be extended on narrow and rutted roads, they were often packed to the footboards with passengers, swinging wildly around bends and taking strips off pedestrians who dared to step off the sidewalk, if sidewalks existed. But my brothers found the belching double-decker bus the perfect nest to rest from their labours at school, more than one would expect.

I knew the transition wasn’t going to be easy. Many are the sightings of two little Burgher boys running from the Welikada junction where the bus terminated, back to our home down 4th Lane, Nawala, a distance of about two miles. Why? Because these two guys would fall asleep in the bus and get carried all the way to the terminal, only to be woken up by the conductor cleaning up for the return journey. After this “over-carrying” had gone on far too many times, Mum finally decided to mount a daily watch at the bus stand opposite our lane, waiting to catch sight of two sleepy heads inside the #198 bus coming from Dehiwala via St. Peter’s College, Bambalapitiya, and should they not disembark, halt the bus by standing in the middle of the road, to retrieve her children before they nodded off to Welikada again.

Childhood disappears far too quickly. My remaining memories of my siblings were when we went to Dad’s office bungalow situated between a lagoon and the ocean in Bentota, years later, after my father received his promotion and began enjoying management “perks.” I remember the night Mario and Dane put on an entertainment for us, acting as two drunks in a bar. From the photo, you will see that they put on a convincing show. Later, I found out that the bottle contained a bit of the “real stuff” to get them into character.

Called to the Bar

Although I wasn’t around much to enjoy the privileges of my Dad’s new job (I got a job and moved to the Middle East at the age of 24), Mario got the full benefit of the best management perk, Dad’s company car, parked at home. Often, it went missing, for Mario had taken it for a ride! And my lil bro hadn’t even got his driving license yet. Poor Dad!

I remember one event just before I headed off overseas. Mario must have been about 14, bursting with the hormones of puberty. He had acquired the habit of coming out to the garden after his bath, with only a skimpy towel wrapped around his waist, standing by the barbed wire fence to talk to the girls in our neighbour’s house, while flexing his muscles from time to time, showing off.

Returning after work that day, I saw our hero by the fence as usual, his Afro hairstyle sticking out, ripped body gleaming from a recent well-water bath, the towel perilously guarding his privates, talking to the girl next door. I guess I must have been cruel, or I wanted to pay him back for all the “caretaking” I’d done, which had derailed my cricket career.

I snuck up behind him and tugged on the towel. It burst free, and Mario howled in embarrassment, trying to cover his crown jewels. Big Brother or not, I was going to get hammered. I took off indoors, his towel still in my hand. Behind me came squeals of laughter and howls of rage. I guess, we were even now.

At the Bentota Bungalow - circa 1977

Postscript: Mario passed away on July 19th 2020, during the middle of the pandemic, of a cancer that took him away in a month. This memoir was inspired by our life together.