MOM’S BEST FRIEND by Patsy Hirst

“I know you don’t want to leave your cat with the neighbor,” I reassured my 8- and 10-year-old daughters, “but when we get to St. Croix, we’ll get a dog like you’ve been wanting to.”

True to my word, the third day after moving into our new home, we went to see some free puppies we’d heard about. Shelley, my older daughter and future vet, took charge immediately. “Why do some have yarn around their necks?” she queried the owner, the matriarch of an old Danish family. “Those are spoken for already; choose one of the others.”

“Sit,” commanded Shelley to the numerous furry bundles rolling around her feet. While most continued their frolicking, one happened to pause momentarily in a seated position. “We’ll take that one,” she declared, “it’s the smartest.” So, our all-female household was increased by one, and the love therein a hundredfold.

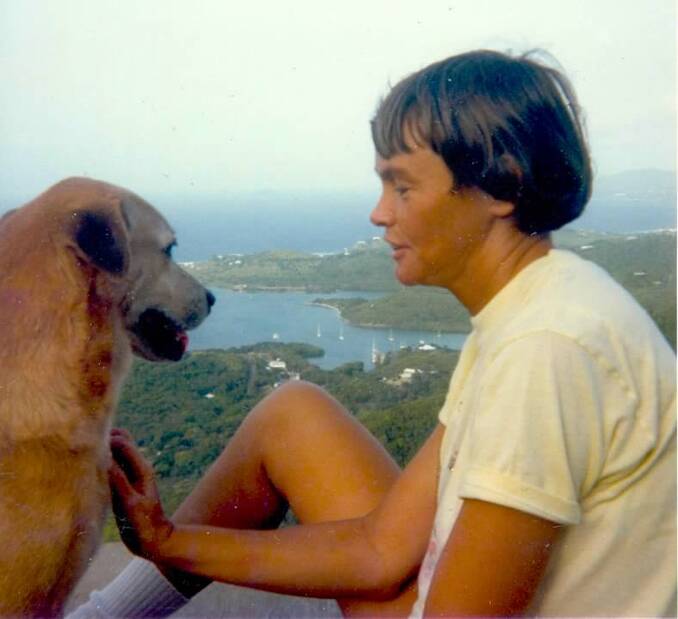

Short-haired, medium sized, Shandy was a true Virgin Islander – a representation of the mixture of cultures that make up our islands. Born in the stables of a 200-year-old Danish estate, she had the quiet, peaceful nature of our original Arawak Indians, the independent spirit of the maroon slaves who declared their own freedom, the intelligence and perseverance of Dutch, Danish, and English settlers who made their fortunes here, and the golden bronze color of a well-tanned tourist.

And her roles were as varied as her background. She dutifully allowed herself to be harnessed to the teacart for circuses, wore a party hat and bobbed for biscuits for her April first birthday, and stood demurely during the performance of her marriage to a neighbor’s dog.

Shandy’s main purpose in life, and she did it extremely well, was simply companionship. It took a while to convince her she couldn’t get on the school bus with the girls in the morning, so she resigned herself to greeting them on their return. She would lie docilly while friends’ small children climbed over her, and tolerated assorted other creatures we acquired – cats, various injured birds, ferrets, a rabbit, and even an abandoned baby mongoose.

Her survival rate surpassed any nine-lived cat we ever had. Hit by a car in her youth, Sandy became a bob-tailed dog. Poisoning caused two late-night emergency trips to the vet, and she was even ‘dognapped’ by the neighborhood witch.

I had always considered our dog’s companionship more for Shelley and Lori, but realized how valuable it was to me when they left the island to attend college in the states. She certainly eased any pangs of empty nest syndrome I may have had, and hopefully I reciprocated in kind. Just as I’d spent 12 years trying to be both parents to my girls after their father left, I now found myself trying to give Shandy the extra attention they had showered on her. Slipping her a dog biscuit each morning as I left for work became a regular habit, and how the girls laughed when I admitted driving through McDonald’s and getting a burger for each of us.

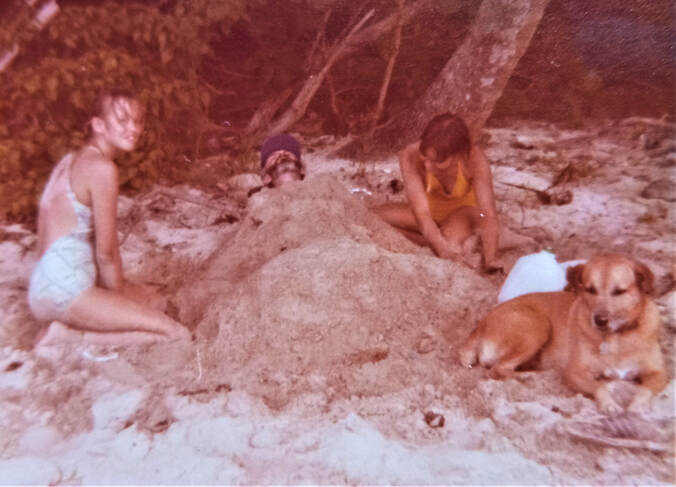

Besides missing the girls, the other thing Shandy and I had in common was a love for the beach. Even as she grew older, and seemed to move more slowly around the yard, a trip to the beach rejuvenated her. Her energy was boundless as she rolled in the seaweed, chased down the beach, and sniffed out crabs, digging faster and deeper till they could not escape. All week Shandy would lie in her spot by the front door, hardly seeming to notice my daily departure for work. But on the weekend, when I headed for the car with towel and cooler, Shandy beat me there and waited eagerly for me to open the door and get our expedition underway.

“We’re going to the beach, Girl. We’re going to the beach.” I drove with one hand, and stretched my other arm full length to give Shandy a reassuring scratch behind the ears. This time she was not perched on the backseat, but lying helplessly in the space made by folding it down.

Frantic and fearing the worst during Shandy’s two-day absence, I finally found her in a nearby field. Attacked by the Mon Bijou drug dealers who congregated at the end of my driveway, she had waited patiently and uncomplaining for my rescue. Though there were no visible injuries, it was obvious she could not move. Love and warmth shone from her eyes, and she drank gratefully from the bowl of water I brought.

“Her spine is not broken”, the new after-hours vet explained, “but very badly damaged. I could put her in a body brace; in a year or so she might get back some use of her legs, but never control over bodily functions or normal walking.” He paused to let the grim diagnosis and obvious solution sink in. Tactfully avoiding eye contact or asking for a decision, he petted Shandy as she lay on the X-ray table. “I’ll give her a shot to make her comfortable; I know she must be in great pain, yet she’s not complaining at all. She must have some Lab in her – they're the Indian of the dog world”.

Still demonstrating great empathy toward my emotional state and the decision I faced, the kind doctor suggested he make Shandy comfortable, keep her overnight, and look into the situation next morning.

I didn’t want to upset Lori, as I knew she had big exams that week. So, because of Shelley’s pre-vet studies and clinic experience, I called on her help and moral support in making the decision to put down our ten-year companion. After a tearful phone conversation, Shelley agreed it was necessary, but we both had pangs of remorse about “abandoning” her to the cold and strange surroundings of the clinic.

“I’d rather take her to the beach and do it,” I suggested.

“You mean have Dr. Jacobs go with you? He probably would if I ask him.”

“No....do you think I could give her the shot myself?” I asked timidly.

“Ask the vet if it’s given into a muscle, or if it goes directly into a vein, which is much harder.....do you really think you could do it?” Shelley sounded doubtful, yet hopeful. The scene was forming simultaneously in both our minds.

At the crack of dawn the next day, a sunny September morning, I donned my #1 Mommy tee shirt, cut-offs and sneakers, loaded a shovel with a long homemade sapling handle into my rusty Honda, and headed East to Pull Point, our favorite beach. A close friend’s dog was buried at the far end amid the sea grass, and I had always known that someday Shandy would be there, too.

I guess I had gone over the plan so much by now that it was as if I were simply a character following a script. Though certainly not without emotion, I played the role from a distance, on the edge of reality. Choosing a site under a seagrape tree, between salt pond and seagrass, I dug, sawed away roots, and dug some more.

By 8 a.m. I was at the vet’s, seated cross-legged on the floor by Shandy’s kennel. She seemed alert and glad to see me; it was hard to believe she was in such critical condition. Both doctors respectfully passed by several times without speaking, then stopped only briefly. “She ate some, but it went right through her. Her internal injuries may be worse than I thought.” It was offered as a casual comment and he walked on, but I wondered. Was he saying this purely for my information, or was he trying to make the decision easier?

He paused on his next pass, and was obviously surprised by my question. “Is the shot intramuscular or intravenous?” I asked, both acknowledging my decision and hinting at my plan. Seeing that he suspected but did not totally comprehend the reason for the question, I briefly related the conversation with Shelley. “It must be in a vein,” he stated.....”but, I could insert a catheter for you.”

Shelley says the most important thing she’s learned in working for vets is that you must ‘treat both ends of the leash’. These doctors were experts. Shortly the two sympathetic, understanding doctors were loading Shandy into my car for that last trip together.

“We’re going to the beach, Shandy. You’re such a good puppy.” It sounded so natural, but could I really play out this last scene?

Parking as close to the sand as possible, I raised the hatchback, gathered the four corners of the brightly-colored beach towel around the dog to form a sling, and carried the burden onto the sand. I placed Shandy facing the water, as she so often lay to relax after a romp on the beach. The sea breeze ruffled her floppy ears as she scanned the shoreline, ready as always to protect me from any intruders. Sitting beside her there, as I’d done so many times before, I offered her water and dog biscuits, cuddled her head in my lap, showered her with love and praise. But the catheter protruding from her foreleg, and filled syringe waiting nearby, would not let me forget the task at hand.

Torn between the desire to spend more time with her, yet wanting to be done before anyone appeared on the beach, I set myself a deadline of 9:15. It was now 9:00. Following the doctor’s instructions, I removed the plastic cap and aimed the needle into the rubber catheter. Trying to detach myself, I let my mind reminisce on happier days. Shandy would race ahead of me down the beach, then run back to me, seeming to ask how I could walk so slowly when there was so much to see and do. When I went for a swim, she would stay alert on shore, watching and paralleling my progress in the water. If I snorkeled too long, she paddled out to check on me. When Lori shinnied up the coconut trees, Shandy circled nervously below.

My left hand scratched and petted, as my right slowly pushed the plunger of the syringe. “You’re such a good puppy...you’re my beach buddy...we love you so much...”. Nestling Shandy’s head in my arm, talking and comforting, I thanked God for this wonderful friend and the ten years we’d shared together. I assured myself that the girls would be comforted knowing Shandy had died on her favorite beach, in the arms of a loving friend.

For the first time, I noticed tiny turtle tracks in the sand, leading from the bushes behind me toward the sea. The hatchlings must have begun their life here last night, I realized; Nature’s cycle continues.

Only one more chore now. It was a physical as well as an emotional struggle as I dragged my load a quarter mile along the beach, up the sandy dune, and through the salt grass to the prepared spot. Having covered and camouflaged the grave, I paused only briefly. “Goodbye, Shandy. Goodbye, my beach buddy.”

Allowed to release at last, waves of emotion rose, peaked, and crashed with those of the sea as I plummeted into the water, mingling its saltiness with that of my tears.