Havana: The Love I Have for You I Cannot Deny – Chan Chan by Cherie Magnus

Havana felt like home. I loved the friendly people, their grace and beauty, the ubiquitous music, and the mojitos. (There never was much food to speak of.) I was anxious to see my friends again and to have some fun. A much better plan than going to Uruguay.

After my midnight arrival at the Jose Marti airport, I went into shock when unexpectedly I had to exchange my dollars into pesos convertibles in order to take a taxi into dark and otherworldly Havana. A new ten-percent government commission on dollars meant that right away I lost a lot of cash. I had no idea of this recent change, that unlike my previous five trips to Cuba, dollars were no longer accepted as legal tender. As an American there was no way to get more money if I ran out. I was panicked that my funds wouldn’t last the nine days of my trip, and there was no fall back position of credit cards or checks for Americans.

Dear Miriam and her tall twenty-three year-old son Fernan were waiting for me at the little apartment I always rented on San Miguel. But now my usual room was rented to someone else despite my reservation via Miriam. You must be flexible in Cuba, a trait that was hard for me. So no matter, we all trooped around the corner to another “friend’s” apartment. All Cubans knew someone who had a room for rent.

I invited Miriam and Fernando to go to the Hotel Telegrafo for mojitos. We toasted to having all of the fun together that we always had during my nine days in Havana and to my new life in Argentina.

In the light of the next day I noticed the apartment was grim. So I went walking the streets in search of better lodgings. I didn’t want to bother Miriam, or wait for her to help me as she always had in the past as she was working a lot and just seemed so tired, unusual for her.

I looked at several rooms in the Vedado neighborhood, feeling proud of myself to be handling the search and the Cuban Spanish on my own. Then I found a restored elegant old palacio with a terraza and many bedrooms, full of marble and stained glass and 40 foot ceilings. The location was perfect. So I took it.

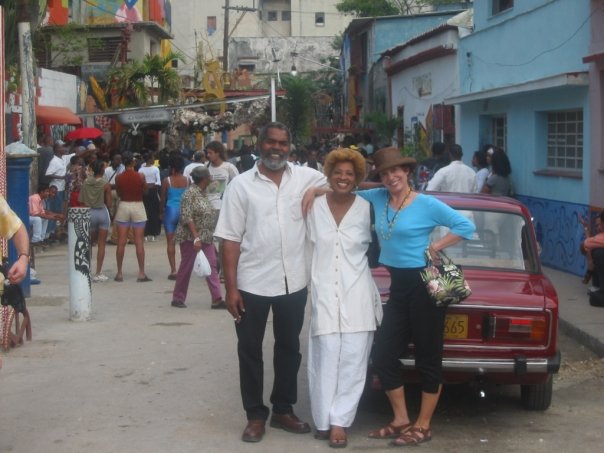

On Sunday Miriam and I walked to the Callejon Hamel for the rumba, an Afro-Cuban music and dance fest with religious roots. We were late and most of the excitement was over. The drummers were packing up and spectators wandered away, some into the studio of the internationally well-known painter Salvador Gonzalez Escalona. We dropped in to visit Miriam’s friend Carina who lived right in the center of the callejon.

As we drank rum and lemon soda and took in the action from the veranda, I saw a man sitting across the way watching us, a very handsome black man with shiny aviator sunglasses. We looked at each other across the alley for a while, and then Miriam went over and invited Rey to join us at Carina’s. We liked one another and made a plan to meet later. Miriam and I agreed that he was a tremendo mangon—hot and sexy.

I was an American woman—a tall, pale-skinned redhead, there was no way I could blend in. It was impossible to walk down any street in Havana day or night without every man on it calling out or hissing in a particularly Cuban-construction-worker way, just part of their macho roles. A tourist woman alone felt vulnerable in Cuba wherever she went, despite the policeman on nearly every Havana street corner day and night as well as CCTV. Even Miriam didn’t like to be out alone without her son or a male friend at night.

I was lucky because I had Miriam who had become close to me over the years. When I was with her I was just another dancer on the Prado in the middle of Cuban friends passing around a bottle of rum. Because of Miriam I went to a Senior Citizens Sunday afternoon soiree in the club on top of the Teatro Nacional and danced old fashioned Cuban Danzon with a dapper oldster in a white suit and white fedora. Because of her I danced at a fiesta in a private palacio, and with friends and family in Miriam’s small home.

I made a mistake to come to Havana for so little time. It was too expensive and too far not to stay longer. I needed time to get used to things. This whole week I felt people pulling on me. I never realized until Rey told me, that everyone was on the take. If someone could get you to rent a room from his friend, or buy a Che Guevara T shirt in a back alley, or hire a car, or go to a nightclub, he got a commission. That was how they lived. Everything was illegal in Cuba, but they survived with that. They were desperate. And I was so used to being independent and alone, that it was difficult for me to adjust to all the attention. I felt like arms were reaching for me from everywhere, like they were drowning and I was on land, helpless to help them. But sometimes I was drowning too.

Now I realized a lot more about my past visits to Havana—the hangers on, the people one collected in the streets. Sure, the Cubans were extremely out-going and friendly and your visit to their country was all they could know of the outside world, but still, if they could get you to spend money while you were with them, they could make a few dollars to buy meat and eggs and soap. With their ration books and pesos, they could only buy the most basic and meager of supplies.

My farewell dinner was supposed to be at Miriam's, as she had cooked for me on my last four trips at her home the night before my departure. But she had been working so hard all week, that I thought I could give her a special treat of a festive dinner at a famous paladar (it was featured in the movie, Strawberries and Chocolate.)

Rey and I went early in the afternoon to look at the menu and check the prices and then I counted my money, so I knew exactly how much it was going to be when I invited the three of them. I could just make it and have enough to pay the $20 departure tax at the airport the next day.

The restaurant, La Guarida, was on the top floor of an incredible 200 year old decrepit mansion that had mostly fallen down, but still people were living in it. Fabulous marble staircases, sculptures, broken stained glass, 40 ft ceilings, ruined walls, laundry flying from the ceiling. It indeed looked like a movie set.

Upstairs we rang the doorbell of the restaurant, and when we entered, I thought we were in New York or a dream. There were three dining rooms and a foyer, photos of kings and queens and movie stars dining there covered the walls. The food was artistic, well-presented and tasty, but not abundant. We ate every grain of rice and each bean. I had enough, but for hungry people it wasn’t sufficient, and the Cubans were always hungry, especially for meat.

When the bill arrived, I noticed there was coffee on it, and we hadn't had coffee. Rey took the bill out of my hand and checked it, and mentioned that it was $84. Miriam and Fernan almost fainted. I hadn’t wanted them to know how much it cost. She said very quietly that she had to work for three months for that much money, and Fernan said there wasn't enough to eat on the plates. They were appalled. I realized then that this was my (American) kind of place, and I should have taken them to a lively Cuban restaurant with music and piles of food where they would feel comfortable. This dinner only underlined the great economic disparity between us. So instead of bringing us closer, it threw up a wall. We always pretended we were the same, that we were sisters of different colors, but in reality we were not.

Usually Miriam and Fernando went to the airport to see me off, but this time we said our farewells downstairs in the street and I felt oh so sad. She was too tired and discouraged to be afraid of speaking against Fidel and the government in public on the street corner where she knew cameras and microphones were recording her words and her face.

Fernan hugged her and said, “Hush, mami!”

And Miriam answered, “I don’t care anymore, I just don’t care.”

I watched them, frustrated and sad and helpless. Tears rolled down my cheeks. This wasn’t what I had wanted, what I had planned on my trip.

I remembered well that gala lunch at the Golden Tulip four years ago when we were a happy group of Cuban and American women dancers getting to know each other across the political, cultural, and linguistic divide. But then last year Miriam and Fernando were forced to move out of the horrible place in which they lived to a worse place that was in fact condemned. They also had to pay a fine for living in the first place without permission. Miriam had been living illegally in Havana for decades, because she never received approval to move from her birthplace, Santiago de Cuba in the east.

Miriam has had no working refrigerator for over three years, no TV after her Soviet black and white died, no electricity in the living room, where two posts prop up the ceiling to keep the upstairs apartment upstairs, no water in the bathroom, only cold water in the kitchen, no access to toilet paper, no toilet seat. The many hurricanes that smashed into Havana regularly had just made it all worse for the residents.

It did hurt sensitive people to see how elegant and educated folk had to live in squalor of the worst kind. Many Cubans were able to live better because they found something to sell: a waiter could "get" you cheap bottles of liquor, a cigar factory worker sold out of his apartment, even at the ballet, the only available seats were from scalpers. But Miriam was a journalist; what did she have to sell?

I mulled over the emotions of the evening, feeling so bad, wanting to fix everyone’s mood (Rey was fine. “Why worry about the past?” he said.) I clearly saw for the first time, despite the many suitcases of useful things I always brought to give away, and paying for a bit of good food and fun once I was there, that trying to help my Cuban friends was like emptying the ocean with a teaspoon.

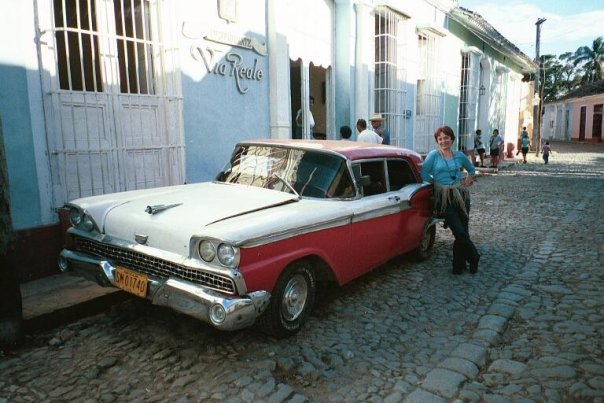

Once in Rey’s friend Luis’ 50s Caddy Sunday morning at 5am, me in the front with Luis, and Rey in the back hanging over the front seat, I felt better. We didn’t meet another car on the entire drive to the airport.

I paid the $20 exit fee, the last of my pesos convertibles. Rey started to cry, his handsome face crimson with blushes and crumpled with emotion, when we kissed goodbye at the security line. “Chan Chan” played on the loudspeakers, and I was crying too.

I just can’t help myself.

(Excerpt from unpublished memoir, Intoxicating Tango: My Years in Buenos Aires)