Dad’s War by Robyn Boswell

The glass case Dad had in his classroom filled with brightly coloured, iridescent butterflies fascinated me as a small child. I was told he’d collected them in Bougainville ‘during the war’ whatever that meant. Every year for several years he’d have a few days of being very unwell, sweating and aching, just like the flu, but I was told he had malaria which he picked up ‘during the war’.

As I grew older I was fascinated by his collection of pamphlets, written in Pidgin English and Japanese, that were dropped out of planes. Sometimes he’d amuse us by talking to us in Pidgin English which he seemed to have picked up quite fluently. I’d thumb through his and Mum’s ration books, wondering how they had managed to survive on what seemed to be meagre pickings.

Unlike others who’d had traumatic war experiences, Dad was always open about his time in Bougainville, but it wasn’t until shortly before he died at 96 that he told me the full story.

When the war started, Dad was a young teacher, happy in his new career. He always wanted to be a pilot and was fascinated by aviation all his life. When he was a little boy he was given a model plane for a present. He adored it, climbed up a tree with it and jumped out thinking he could fly with the plane. That didn’t end well!

At the start of the war he imagined that he could fulfil his life’s dream of flying. Unfortunately, or perhaps, fortunately, his eyesight wasn’t good enough to be a pilot. Teachers, as essential workers, were exempt from call up although they could volunteer. The first few years of the war Dad chose to stay focused on his teaching career.

Towards the end of 1945, the war in Europe was mopping up and the Pacific War looked as though it was coming to an end. With a young man’s sense of adventure, Dad decided he should sign up before it was too late. A friend told him that they were looking for cipher officers in the Pacific, so if he wanted to be sure of getting overseas he should sign up for that. He joined the RNZAF and headed to Ohakea for training. There he learned the skills necessary to be a cipher officer, including Morse Code, which he could still recite at the end of his long life.

In the second-half of 1945, his longed-for overseas posting was confirmed and he was actually given a choice of which of the Pacific islands he could go to. He’d heard that Guadalcanal and a few other places were still very much hot-beds of warfare, so chose to go to the island of Bougainville, which is in Papua New Guinea.

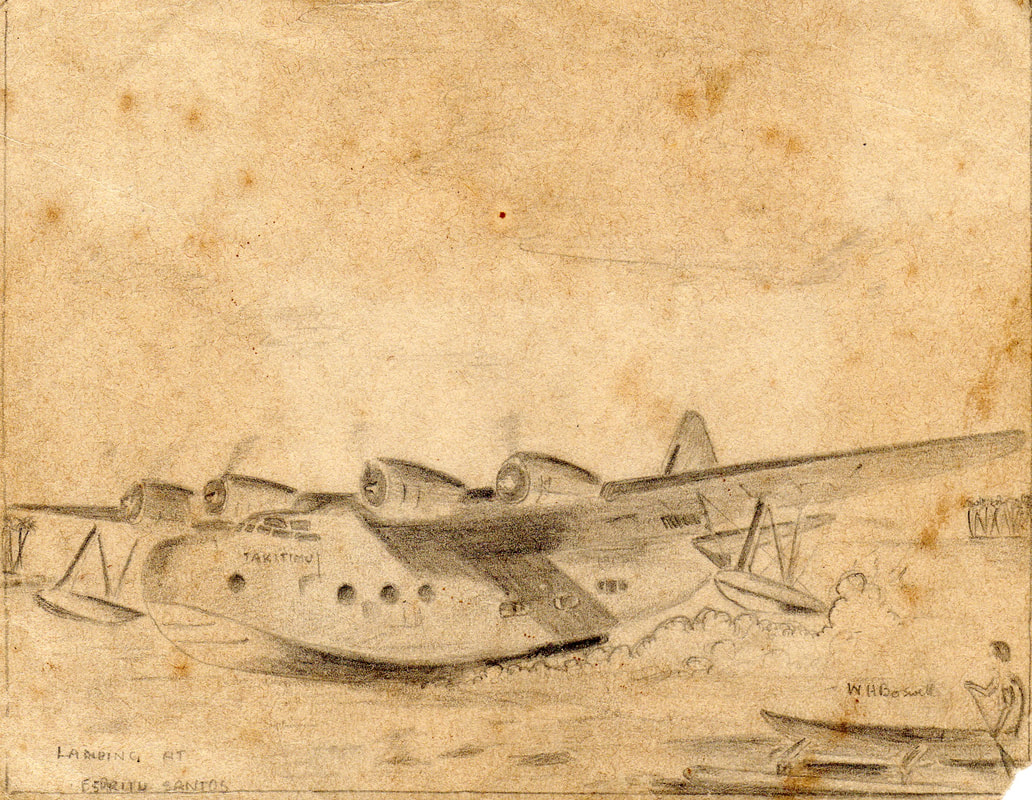

With great excitement he flew up to Noumea on a Sunderland flying boat and on to Bougainville in a C47. Unfortunately they hit a vicious storm and with the Sunderland not able to fly above 19,000 feet, they bore the brunt of it.

In a letter home, which he wrote on the plane in the storm, Dad wrote, “That took the wind out of my sails! We went up and then down with a devil of a wallop that time. We have just been through a first-rate storm. It was just a case of hold on and anchor your stomach down. As you can see by the writing we aren't out of the cactus yet and it looks like more ahead. You have no idea what those drops feel like. Once I thought we would never reach bottom. We dropped like a stone for what must have been fully 500 ft and then we were shot up again almost as fast”.

An exciting trip indeed!

Bougainville was still half occupied by the Japanese and half by the Allies. The airstrip they landed on in Bougainville had been built from crushed coral with Marsden matting (big sheets of steel) over the top to help keep it level. By the time Dad arrived, most of the Americans were gone and it was used by the RNZAF who were flying C47 Corsairs.

Dad was introduced to his ‘office’, a small radio shack which was for safety and security situated about 10 miles from the main camp. There he started his deployment as a cipher officer. His main role was decoding and encoding classified, top-secret messages. The messages were copied down by signalmen then passed on to the cipher officers to code and decode. Many of the messages were top secret and not for common knowledge. One day Dad received one very special classified message to decode and so he was the first person on Bougainville to know that the Japanese had surrendered.

Due to the privileged position he was in, Dad and his fellow cipher officers were able to send uncensored letters home, although they were still very circumspect about what they wrote.

The main camp had originally been set up by the Americans, but now was filled with mostly New Zealanders and Australians. There were few Americans on the island although there had been thousands earlier. It wasn’t very large, but it was a very active camp with patrols coming and going continuously. In a letter home, Dad wrote: “Well, I don't seem to have ever told you much about the camp here but there's not much to tell really. We are right on the edge of the jungle and it’s quite a small camp all by itself. It is only about a mile down to the beach and very easy walking so we are really in an ideal spot. We are well back from the main road so no-one interferes with us”.

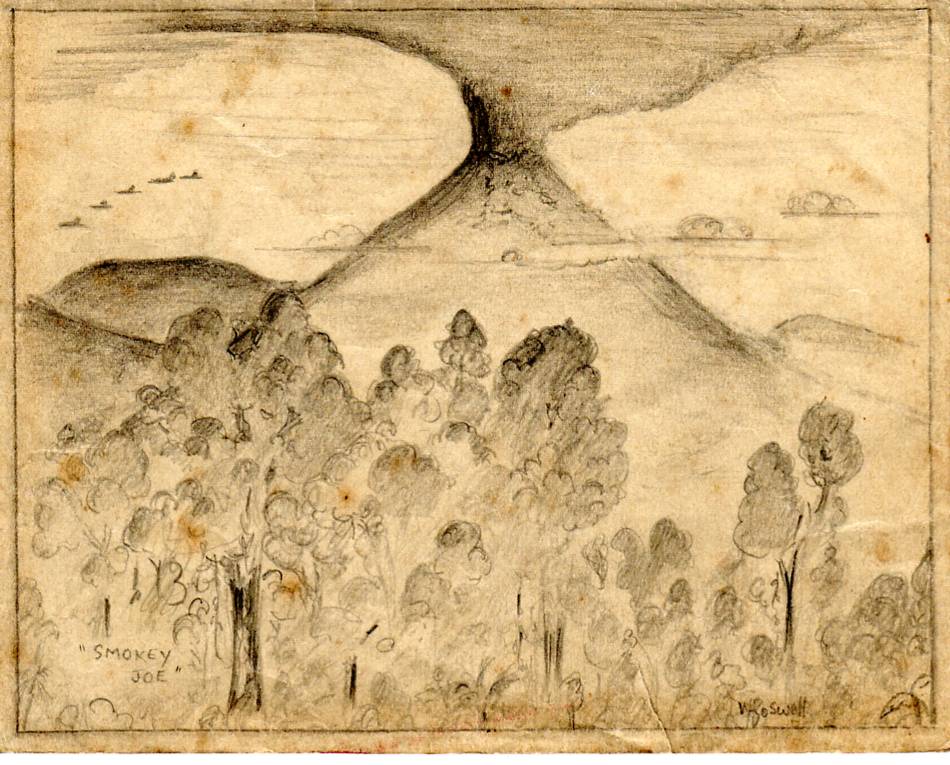

The camp was at the base of Mt Bagana, an almost perfect cone in the centre of the island. Mt Bagana, an active volcano, erupts almost continually. Every afternoon around 4pm, the volcano would growl and rumble and occasionally burp out hot lava which fortunately was too viscous to run far. It kept the troops entertained and they dubbed it ‘Smokey Joe’.

In one of those strange quirks of war, one exciting night a Japanese patrol went through the camp. Fortunately they were hugely outnumbered and were more scared of the men in the camp than the men were of them, so they scarpered very quickly! No harm done on either side.

The main entertainment was an open-air movie theatre that helped to fill in a lot of downtime. The seats in the theatre were the empty aviation fuel 44-gallon drums. One memorable night they were entertained by Gracie Fields. How brave were those young women who flew to so many of the wars’ hot spots to keep the troops’ morale up? Until his dying day, Dad loved Gracie Fields and especially ‘We’ll Meet Again’.

They also played a lot of volleyball, which the Americans had introduced. It was then that Dad discovered a new leisure time activity and collected butterflies since many species were prevalent on the island. For years afterwards these were a valuable nature study resource in his classrooms and a source of fascination for his yet to be born daughter.

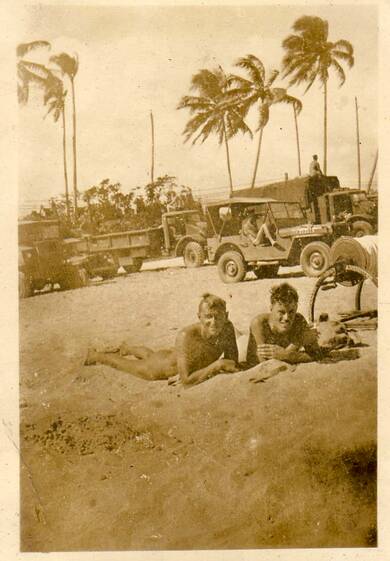

He also managed to get his hands on some pencils and paper and recorded everyday life in the camp. These are still our very precious possessions. He was such a talented drawer but didn’t really take it up again until he retired and we went on a three-month camping tour of Australia. The coloured pencil sketches he did during the trip have left us with enduring memories – both of the trip and of his talents.

The beach was very popular for sunbathing and with no women in sight, clothing wasn’t required, as Dad’s photos attest. As he said “Everyone was as brown as a berry”.

Dad was always known for his home handyman skills and loved building and creating. In another letter he described a time when he used ‘Kiwi ingenuity’ to make his camp more like home - “I have been very busy in my last two or three days off. I have been fixing up our tent, or my part of it anyway. The crowd I am in with are very decent chaps but a little slap happy if you know what I mean. They never seem to bother over much. However I have got to work and put myself a floor in and have built up the side of the tent with wire gauge etc. I put the electric light in yesterday at the risk of life and limb. These lazy devils here were subsisting on a torch! However I acquired the necessary fittings including a 150-watt bulb so our lighting troubles are over for now.”

One day he decided to take a walk up the narrow, steep track to the front lines ‘just to see what was happening’. Part of the way up the track he met a local man known as ‘Black Jack’ who was accompanied by an entourage of several wives and children. Dad attempted to engage him in conversation, but Jack just said “No, we go”. It wasn’t until he got back to camp and his mates heard the story that he realised just how lucky he’d been. Apparently ‘Black Jack’ had the propensity to wield the long spear he carried and run people through with it. Fortunately he was usually more forgiving of the allied troops than the Japanese.

Dad made it to the front lines where the troops were dug in, waited for a lull in the gunfire and headed back to the camp at a rate of knots. He was certainly relieved that that wasn’t where he had to spend his war. When I was young I was told he saw a Japanese soldier shot out of a tree. He never referred to it again and certainly didn’t tell me when I was recording his story. I suspect it’s the trauma of seeing that magnified many times that has stopped so many veterans from sharing their war stories.

This trip to the front led to an amusing side note that has long been a family story. Dad wrote home about this adventure. His Mum was so proud of him, that she contacted the local newspaper and there was an article about it with the grand headline - ‘Kamo Flyer Visits the Front Lines’!

Dad was in Bougainville just long enough to qualify for an overseas service medal. He returned home on the SS Wahine, which was crowded with returning troops. Returnees got a ration of a carton of cigarettes every week, so he saved his for his mother who was a smoker. He stacked them in his kitbag for the train journey home from the South Island. When he got home he opened his bag and the cigarettes were gone. All his life he remembered how devastated he was. There was a plus side in that it put him off smoking forever, probably a contributing factor to his long and healthy life.

Another enduring souvenir of his time in Bougainville was the malaria that he contracted. For years afterwards he would have a recurrence of it once a year until it finally faded away.

On his return, Dad went back to teaching at the same school he had left to go to war. He met Helen, a brand-new teacher. She wasn’t terribly impressed by the young man roaring into the school on his noisy motorbike, wearing a flying helmet with a white silk scarf fluttering behind him. She must have softened up over time.

Eventually they took their classes on a class visit to the coal mine where my grandad worked and as they say, the rest was history. Their first date, down a coalmine with 70 or so children, is a favourite family story. After bringing up 3 children, living in the idyllic Parua Bay, Helen tragically passed away with cancer at the young age of 39. Although solo fathers were almost unheard of in the 1960s, Dad took on the challenge, wouldn’t listen to his bunch of old aunties who thought it wasn’t ‘men’s work’ and became a solo father to we three children. He was principal and deputy principal of 3 schools at the same time as single-handedly bringing up his family. He finished his career as principal of what was the largest intermediate school in New Zealand at the time.

After his retirement, Dad belonged to many organisations in town, was very active in Rotary and wrote an ‘Around the Schools’ column for the local newspaper, which kept him in contact with education which he so dearly loved. He remarried at 70 and he and his new wife went on to celebrate over 20 years of happy, fulfilled life.