“Sailing By” Part 1 by Ronald Mackay

A short piece of music took me by surprise this evening, drew me back in time and memory provoking nostalgia tinged with regret.

***

Music, surely, carries the deepest form of meaning. As an admirer of the written word, I find my certainty odd. More often than to music, I listen to the spoken word. No longer do I pretend to play a musical instrument. I read and I write.

Early, I heard music, rather than listened to it. From the age of seven, my big sister took piano lessons in Miss Hunter’s parlour near Baxter Park. My mother charged me to wait until her lesson was over and accompany her home on the number two bus from Mains Loan that cost us each a ha’penny.

Maybe that happened only once or twice. More likely, we walked home. In the 1940s, two ha’pennies made a penny and we practised the proverb: “Take care of the pence and the pounds will take care of themselves”.

Our mother would summon my wee brother and me to hear our sister practice scales and the short classical pieces Miss Hunter set her.

The three of us, comfortable in the absence of our father, sat and listened. False starts and repetitions quickly turned into skilled performance. Vivian grew into a talented pianist; Miss Hunter’s star pupil. We listened with pride. Music comforted. My comfort was doubled because I knew that whenever our mother summoned us, she was drawing our attention to something worthy. And not just music. She would summon us to show us how to break eggs and whip them with flour and sugar in a bowl, to skin and quarter a rabbit, make porridge and custard without lumps, to peel and remove the eyes from Golden Wonders for potato soup. She might summon us to watch in wonder as the sun set over the Sidlaw Hills as we stood silent and intimate in the gloaming, aware of having witnessed something beyond the power of words.

Behind those summonses lay the responsibility she assumed for encouraging us to make sense of a baffling world, to know right from wrong, to appreciate beauty, to open our eager minds and young bodies to nature, to our place in it, and to feel comfort in the transcendental.

With music and without, she taught us the difference between banality and beauty, the mystery in the revelation of an encircling world I found so baffling.

***

My earliest feelings were stained with bewilderment on a backdrop of music. Not surprising, perhaps, for a child born into the Second World War, brought up in a family of women constantly busy with mystifying tasks. Husbands, fathers, were “away”. Unpredictably, they came home “on leave” but with barely enough time to shed their uniforms before being “recalled”. My world was what surrounded me: my big sister, my mother, my wee brother, my grandmother, Aunty Mabel, occasionally my grandpa. A comfortable stone house, a flagstone-floored kitchen, a vegetable garden, orchard; the mystery of the radio that demanded delicate tuning, whose wet cell battery had to be exchanged when it died to silence. The urgent words of the BBC, jolly songs of sadness disguised as hope.

***

As years passed, Vivian first, then my wee brother became music makers, played the piano, sang. I was proud that, at fifteen, my sister accepted the role of organist and choirmaster in St James. Such dedication meant morning and evening services each Sunday, choir practice on Thursdays.

***

In our music classes at the Morgan, I was exposed to “do, re, mi, fa, so, la. ti, do”. The lines and notes made no sense, so I learned to sing scales a fraction behind my classmates. My ploy worked until Miss Blackwood, with girlish-cut black hair, suddenly halted a rehearsal for the Hallelujah Chorus.

She raised her baton in annoyance.

“Mackay! On your own. From the fourth bar.”

Trapped, I stood silent, exposed.

“You can’t read the notes?” She expected no answer. “Tomorrow, mouth the words. Don’t sing. Your timing’s off.”

***

Clarinet was my next effort, Again, I was found out.

“Come back when you can read the notes!”

I never returned.

***

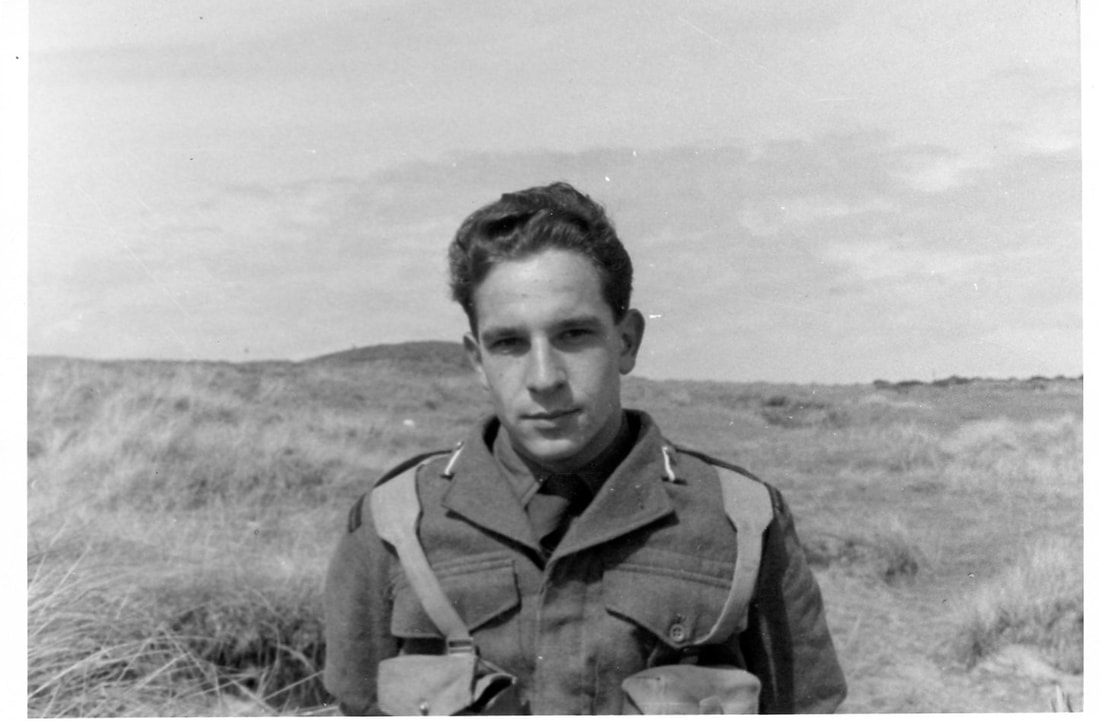

With expectations of learning to play the bagpipes, I joined the 3rd Battalion Gordon Highlanders. Once more, I played a fraction behind the others and got away with it, until we reached pieces that demanded the D grace note followed by the E grace note. In the dead of a Highland winter, in an army camp in the rugged Cairngorms, the pipe-major silenced us.

“Mackay! Let’s hear that E grace note on low G.”

In my ear, I could hear the double bubble of the two grace notes but my pinkie refused to cooperate. It held my ring finger back a fraction. That fraction counted.

“Practice in the corridor, Mackay! Practice that fingering till it’s perfect.”

For thirty minutes I practiced. Got it, almost, and went back.

“Not good enough! Leave your pipes here. Tell the RSM I’ve sent you to join the Winter Warfare Patrol.”

So ended of my musical aspirations as a player, but turned me into a man comfortable with arms. Within that close-bound group of winter warriors, I learned how an eleven-man patrol on skis behind enemy lines might create havoc and distress. I learned to select the weapons, many silent, that would best support each operation.

While my expertise with arms was acquired as a consequence of my musical ineptitude, the deficiency didn’t interfere with my musical appreciation.

***

Some pieces continue to haunt me.

The opening bars of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony take me back to the early 1940s. Father, uncles, soldiers, came and went. The repeated motif: "dah-dah-dah-DAAH", one uncle confided, was secret code for "Victory". From then on, when the BBC played "dah-dah-dah-DAAH” I was comforted knowing that all would be well. When Victory Day arrived, it was the fulfilment of what I’d long expected.

***

Music has continued to grow beyond my ability to express its meaning in words. Some musical phrases speak as if from a realm beyond the everyday, reminding me of my modest place in the world, of my triumphs and my shortcomings. On occasion, music can be warm and comforting. More often it causes a longing, suggests a duty unperformed, a duty too late, now, to be discharged; a pledge unfulfilled.

***

“Sailing By” first struck me lying feverish in a cramped bunk as a crewmember of a Seine net fishing boat registered in Macduff. The skipper had sold his catch in Aberdeen. He was a crew member short when I turned up, sent doubtfully from the Fisherman’s Mission. The Mission manager was uncertain, because I had no deep-sea experience. But because I was a youth, I was as sure as he was uncertain that I could fill the gap and so let the skipper get his Seine netter back to sea for another three days and nights.

The skipper looked at me, reluctant. My Angus accent told him I wasn’t from the North-East, nor from a fisher family. I answered his questions economically, as much to give no encouragement to my creeping headache, as to match his terse directness.

***

I had no need to tell him why I was seeking work, that I’d come to Aberdeen from Dundee at the bidding of the Dean of Agriculture, expecting that he would confirm my application to become a student at Marischal College.

Instead, holding my school exam record in his hand, he declared, “You’re weak in maths.”

“I spent the summer studying and retook the exam in August.”

“You failed the first time in June.”

“I passed six weeks later.” Unimpressed, he examined the evidence in my file. “I can’t admit you.” Then, university admission was competitive.

That afternoon, I learned to recognise a brick wall. Later, I would learn how to loosen a brick, even to climb over, but that afternoon I was stunned, I held authority in too high respect to argue, felt the grip of ‘flu coming on.

***

The skipper broke the silence. “An experienced hand’s what I need.” I heard the indecision in his voice. He continued to scrutinise me. Then: “I’ll tak a chance on ye, man. Come awa aboard.”

I was the fifth hand on his 50-foot Seine netter powered by an unfailing Kelvin diesel.

“That’s yer berth. Better ye sleep noo. We’ll soon be shootin and haulin nets non-stop”.

***

I remember squeezing into my berth fully clothed, the comforting thrum of the Kelvin as we cruised out of the harbour, the abrupt pitching as we crossed the bar into the North Sea and the heightened roar as the Kelvin’s power drove the wooden boat into the wind.

Lying suspended between consciousness and sleep I was mesmerised by music. The BBC orchestra playing “Sailing By”. Then came the shipping forecast with its equally mesmerizing names, Faeroes, Bailey, Cromarty, Hebrides, Dogger, German Bight, Humber, Rockall, Trafalgar. I remember hearing the windspeeds and the gale warnings.

***

Unable to rouse me, the first hand gave up. Now a man short, the crew shot the weighted net down to the sandy bottom.

I remember nothing more until, still unsteady, I was put ashore in Peterhead.

“Sorry, man.” The skipper’s apology was sincere. “A sick man’s nae use tae me. Get yersel’ a doctor.”

I understood.

He headed back out into the darkness of the roiling North Sea with an experienced fifth hand from the Mission to make up for lost time.

***

All that night and the next, I lay sweating in the Fisherman’s Mission. Barely conscious I’d hear the radio play “Sailing By” then the shipping news, the weather forecast for Faeroes, Bailey, Cromarty, Hebrides, Dogger, German Bight, Humber, Rockall, Trafalgar.

The music and the words that followed brought a fusion of feelings, an inseparable amalgam of guilt, remorse, consolation. Guilt for my shortcomings. Remorse at failing the young skipper who’d taken a chance on me. Solace in the music for the Dean’s rejection.

***

This evening, Ronald Binge’s “Sailing By” brought back memories of eager aspirations and practical needs, reminded me of opportunities too lightly discarded, duties unfulfilled, some difficult to come to terms with. Wisdom tells us, however, that the gate to liberation stands foursquare on the path of loss. A gate that can be opened to a more reassuring future.