O’er the Bridge that Spans the River by Ronald Mackay

“Je pense qu’il reviendra.” Dr Hutchison’s eyes searched for the inattentive. “Mackay!”

The sound of my name shattered a day-dream.

“Mackay!” His voice was edged with impatience.

***

Spring 1959. Dundee. An unusually warm Friday afternoon, for Scotland. Final class. Higher French. Revision before the final exams. Verbs of hope that require the subjunctive in the negative when there is little likelihood that the action will occur. The monotonous rattle of a pneumatic drill removing cobble-stones had enticed me elsewhere.

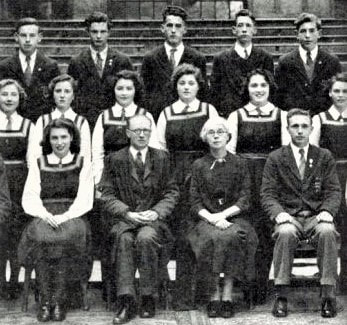

Dr Hutchison served also as Deputy Rector of the Morgan Academy. Like all our teachers, he’d been christened with a nickname. Bunny. No, not from any animal resemblance but from an association that went: Hutchison. Hutch. Domestic rabbits live in a hutch. Bunny is another word for rabbit. Bunny-hutch. By such crooked, schoolboy logic, Dr Hutchison became Bunny. Behind his back, that is.

***

The limp slouch of pupils suggested unaccustomed inattention. Bunny was much respected and more greatly feared. We seventeen-year-olds were just beginning to acquire the wisdom to distinguish between fear and respect.

Rumour had it that Bunny had played a major role in Italy during the War as an officer in military intelligence. Like all our teachers who had served, and they were many, Bunny never talked about the War in other than oblique terms.

Nevertheless, it was whispered that his pursuit of intelligence had driven him ahead of the allies advancing through Italy. One sunny day, he entered a village church to admire its frescoes and came face-to-face with a group of Wehrmacht officers sheltering from the heat. Bringing himself to attention, his Webley inaccessible in its awkward holster, Bunny had smiled ruefully at the astounded officers, hands spread. Then in perfect German:

“In the King’s name, I declare you my prisoners. You are surrounded by my armed patrol. To respect the sanctity of this chapel I will not draw my revolver but you must lay yours down.”

Cucumber cool, Bunny had marched the disarmed officers out of that cool, holy place, handed them over to his driver whose Tommy-gun with its hundred rounds in the drum encouraged their cooperation, and radioed headquarters to report that he had taken five valuable prisoners. Before being escorted off for interrogation, the senior officer had stood to attention, saluted Bunny and in perfect English announced:

“Sir, I congratulate you on your presence of mind which is a credit to your rank, your regiment, your King and to the unequalled British sense of humour.”

***

I struggled to recall the rule and the subjunctive form of the verb.

“Tell him, Macgregor!”

Macgregor smirked. “Je ne pense pas qu’il revienne.”

“Mackay, can you repeat the correct answer exactly as offered?” Bunny waited.

***

Bunny’s questions could mean different things at different times. Woe betide any pupil who, out of innocence or an unseemly sense of humour, failed a Bunny-question.

Had I dared to offer a Macgregor-like smirk before repeating the correct answer, I’d have been guilty of insolence and justly punished. We learned to interpret Bunny’s tone of voice, give due weight to his facial expression and always take context into consideration, before daring to reply.

Experience had honed the skills that allowed us to know what his questions meant and to respond appropriately. Failure to do so constituted insolence and, in even the slightest degree insolence was not tolerated at the Morgan Academy. It was punishable by six-of-the-best delivered on each hand by the teacher disrespected. Punishment was administered by a Lochgelly, a thick leather strap twenty-four inches long and an inch wide. The end that struck your outstretched hand was split like a serpent’s tongue to intensify the pain. Adroitly administered, Six-of-the-best brought tears to the eyes of the bravest. The Lochgelly encouraged diligence and effort by discouraging repetition of the same offence.

***

“Je ne pense pas qu’il revienne.” I repeated the answer without the smirk. Bunny nodded, satisfied that my pronunciation was closer to the French than MacGregor’s. My determined improvement cancelled out MacGregor’s earlier triumph.

However, the moment had triggered something in Bunny. Some intuition that demanded he teach us a lesson, one that he knew we must learn before we almost-adults, finally and forever, and in the words of our school song, passed:

O’er the Bridge that spans the River,

Soon we pass away alone,

Leaving comrades keen and clever,

For the lure of the unknown.

But, though much or mean our treasure,

Though our fame be great or ill,

We shall still recall with pleasure,

Our dear “Morgan” on the hill.

Soon we pass away alone,

Leaving comrades keen and clever,

For the lure of the unknown.

But, though much or mean our treasure,

Though our fame be great or ill,

We shall still recall with pleasure,

Our dear “Morgan” on the hill.

“Listen!” Theatrically, Bunny cupped his ear exaggerating the gesture perhaps to admit, after all those years of unremitting discipline and before we passed from his guardianship, that like us he too, was human.

With that simple gesture Bunny assisted us across an invisible threshold to a place where the customary differences that separate teacher from pupil were intentionally blurred.

The class rallied to his call, conscious of the incandescence of the moment but uncertain of where it might lead.

“What do you hear?” He paused. We knew it was a question he himself would answer. “Repairing the tramlines. Men with shovels, wheelbarrows, a pneumatic drill. They earn a decent living. You can join them. Any of you.” He scanned the eyes of each pupil and, it seemed to me, held mine a fraction longer.

“You can join them as a common labourer right now, if you want. They’re crying out for you. Crying out!” He let his repetition sink in.

“Why are you in here and not out there with a shovel?”

His eyes drilled into me. I decided that this was a real question.

“I must complete my school education, Sir.”

Without altering his expression, he focused on another pupil and then another. Answers came fast.

“My dad’s a labourer so my mum wants more for me and my brother, Sir.”

“It’s better to be educated, Sir.”

“I’m here so I can get a good job when I leave, Sir and be better paid.”

“Education.” Bunny let the word sink in. “What does it mean to become educated?” His eyes roved over the class. We were triggered now, on a treasure-hunt that could lead anywhere.

“With an education, Sir, we’ll pass our final exams.”

“Sir, an education means to get good marks on all our subjects.”

“If we’re educated, we can be professionals, Sir. Lawyers, surveyors, accountants.”

“So we can apply to study medicine at St Andrews, Sir.” Mahaddy’s mother, a jute-mill worker, was ambitious for her son to become a doctor.

“Sir, so we can join the Civil Service, work as a reporter for D.C. Thompsons, join the Merchant Navy, be a nurse, a teacher…”

Our answers came thick and fast even though none of us had pondered the matter deeply. We repeated the hopes, beliefs, aspirations, commands and dreams of our parents. Most working or lower-middle-class, all parents wanted “more” for their sons and daughters though what that “more” consisted of was hard to pin down.

Bunny relaxed. His expression suggested that none of our answers was adequate; that his mission was to enlighten us.

“Educate…what’s the origin of the word?” We were expected to answer.

“Latin, Sir. Educare. To rear.”

“Educere, Sir. Latin for to bring forth.”

Bunny nodded. “The education we offer you here or in any school, is a set of tools that you can use to cultivate your minds, so you can grapple with the best that mankind has produced.” He paused. “What’s another word for the best that mankind has produced?”

We could see from his eyes this was not a question we were supposed to answer.

“Culture. Culture represents the best that mankind has produced. And culture comes from the ‘rearing’ of educare and the ‘bringing forth’ of educere. Acquiring culture depends on being educated. The job of every teacher here, is to encourage your growth, to prepare your minds so that you can strive to become cultured citizens of this country.”

Bunny was silent. Then:

“Why are you here, here at the Morgan?”

We could tell he was going to enlighten us.

“You’re here because you’ve shown yourselves capable of learning. You passed your qualifying exams. You’re in the upper quartile.”

We didn’t know what or where the upper quartile was but upper, we guessed, had to be better than lower.

“You’ve got what it takes. All of you. Your years in school instead of wielding a shovel is not time wasted. What you learn elevates your spirits, increases your knowledge, adds to your experience and understanding of art and literature, physics and chemistry, biology and history, and languages including your own. Education isn’t wasted. It fulfils you.”

Bunny looked at each of us.

“To receive an education ensures that you learn what’s worth learning – but it implies more than just learning.” Bunny paused. “It necessarily involves your taking responsibility for pursuing that learning for the good of mankind. So you can stand with your back straight, eye-to-eye with the world and help fix it when it goes wrong. And believe me,” he paused and looked into a place far, far from our classroom, before coming back:

“Believe me, a lot can go wrong with our world. I’ve seen it with my very own eyes.”

Our attention quickened. We were used to being told that to take responsibility was our moral duty. We weren’t used to being told by a teacher that the world could go wrong and when it did, we would have the responsibility of setting it aright.

“Here at the Morgan we offer each one of you – if you want it -- a sense of duty, a moral code, a sense of the importance religion and tradition play in tying us together as a community. And to guarantee that binding holds, we bear the responsibility for being always on the lookout for social improvement.” He paused. “Improvement that everyone can enjoy, not just you or your family group. It’s up to all of you to rise to this challenge.”

“Do we have a choice, Sir?” A lone voice cut into Bunny’s message.

Without permission being first granted, questions were frowned upon at the Morgan.

“Who spoke? Stand up!”

David Littlejohn stood. Had it been anyone less-deserving than David, the question might have been heard as an impertinence demanding six-of-the-best. But David was the best among us. Bright, thoughtful, always respectful, and serious beyond his years.

We held our collective breath.

“Do we have a choice?” Bunny repeated the words slowly. “Good question, Littlejohn.”

He removed his spectacles and massaged his forehead.

“Not everybody has the ability to imagine a world beyond themselves, beyond their own puny lives. So pursuing an education, striving to acquire culture is not so much a choice as the consequence of a gift. All of you possess that gift. You have proved it. But lots of men and women out there who went to work in manual jobs at fifteen possess that gift too.”

He replaced his spectacles.

“And, more’s the pity, you can abandon your gift. Some of you will become professionals but will let that gift wither, the gift that allows you to look beyond your own limited perspective. You’ll let your world shrink to merely servicing your own wants and ignoring the broader needs of your community, of our society.”

“So education is a continuous conscious choice.” David’s face was serious. “We’re never off the hook.”

“That’s right, David. You always have to struggle for education and the culture that it allows you to access. You must be prepared to strive your whole life, never give up and never, ever let your guard down.”

I knew I was witnessing, consciously for the first time, pupil and teacher in conversation, talking on the same level, man to man. I knew that David Littlejohn was growing up and that the rest of us must follow his example. To seriously listen, to think deeply, and to question Why?

“Do you understand?” Bunny uttered the words as an appeal to our deepest care; not as a teacher but as a fellow human being.

We nodded, conscious that we were being led on an impromptu rite of passage, one of greater importance than our final exams. Bunny, a veteran in the fight for what it meant to be educated and cultured, was offering us a lesson for life, a truth that placed an awesome responsibility on our shoulders. We were conscious in that moment that to shrug off that burden would not only deny our deepest nature, but would place us in unfathomable peril. Perhaps drag our families, our country and our very world into the pit.

Hail “The Morgan” stately, splendid,

Hail the teachers, every one!

Cheer we every goal defended

Every hit and every run!

We would strive with every lesson,

As we strive when at our play,

Learn with every passing session,

“Who would rule, must first obey.”