Tent Pegs and Poles by Susan Mellsopp

In absolute frustration I crawled out of my warm sleeping bag and crept up behind my eldest son. I snapped the headphones against his ears. Looking at me with absolute disgust he demanded to know why I had done that. His out of tune singing night after night was keeping us all awake and I had finally exacted some hilarious retribution.

I had never been camping as a child, but after reading a book about a young couple who cycled around the world pitching their tent wherever the mood took them, I was hooked. Farm responsibilities meant my children had never had a proper family holiday, tenting offered an affordable solution.

A decision was made to travel around the East Coast of the North Island, a place full of lonely but beautiful beaches, magnificent bush walks and friendly small rural communities. Borrowing an old fashioned square scout tent, I soon discovered it had no floor. Rules were swiftly devised – the naughtiest child had to fill in the toilet we dug at each free remote camping site, and help pack the tent. After staying in small coastal towns where old Maraes, early wooden churches and huge pohutukawa reigned, we finally relaxed. Swimming several times a day became the norm; in the icy Motu river with our car parked in the stony riverbed, in rolling surf on deserted beaches and in sheltered inlets.

We spent several hours enjoying the infamous town of Ruatoria where the main mode of transport was a horse. The local radio station blared its message of national defiance everywhere. Asking a local farmer if we could camp in his paddock next to the beach, he readily agreed for the sum of $10. I had, much to the family’s annoyance, brought a banana box full of library books to read. I slept and read all day while the children ran wild exploring the beach, the surrounding dry hills and climbed trees. Showering under a freezing cold waterfall was exhilarating. We swam in the blue Pacific waters and ate fish caught just 10 minutes earlier.

Arriving in Tolaga Bay a change of diet was essential. Meals had consisted mainly of cornflakes, bread, and packets of rice risotto padded out with cauliflower, courgettes and tomatoes purchased at roadside stalls. The smell of the local fish and chip shop was irresistible. I ordered fresh snapper and chips which arrived wrapped in many layers of newspaper. Eating our greasy treat sitting on the long wharf with our feet dangling over the edge was fun until one of the children spotted a sea snake in the water and pandemonium ensued. Returning to our tent at dusk a noisy rustling and snorting greeted us. I shook the tent and a terrified half grown wild pig emerged with a fresh lettuce in its mouth. The following night further rustling woke us. Not a pig but a curious large hedgehog was searching for food.

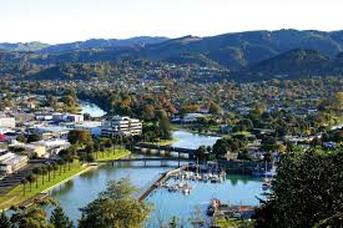

Nearing Gisborne, the only large town on the East Coast, we were all rigid with excitement, civilization! Our dreams were short lived. After two weeks living rough we could not cope with the bustle of busy clean people and the overwhelming noise. After a quick trip to the supermarket then the bakery for fresh bread and melt in the mouth doughnuts full of real cream we were back on the road.

Mahia was a haven of peace and tranquillity. Situated in sand dunes among pine trees, we put up the tent away from other campers. The children roamed freely, often returning only for tomato sandwiches, baked beans or the inevitable rice risotto. I have never purchased this delicacy since. A group of louts, denied entry by the proprietor of the camp, decided to exact revenge. At 2am they set fire to pine needles around the perimeter and soon there was a thick smell of smoke in the air. Unable to wake my eldest son, eventually I screamed fire and shook him violently. Leaping up he grabbed a shovel and became the hero of the night as he poured sand over the fires.

Reluctantly turning towards home we headed for Lake Waikaremoana. Erecting the tent in a free Department of Conservation camping area, curious kiwi rustled and called each other around our tent all night keeping us awake. Dishes and children were scrubbed in the clear fast running icy river. Miles of remote bush tracks became our playground as we explored deserted silent lakes.

Camping holidays became a way of life. We purchased a large three bay tent, Antarctic weight sleeping bags, a two ring gas cooker and toaster. We travelled to Northland to visit the places of importance to our colonial history and spent four weeks camping around the South Island. A Victoria Cross recipient allowed us to stay on his farm, and my daughter was almost killed by a hooligan driving at high speed through a camping ground in mid-winter. I woke to water lapping over my air bed at a pony club camp. Our son was bashed over the head with a spanner by his frustrated travel weary sister. He was indignant when I took him into the ladies toilet to clean up the blood. Our tent was filled with vomit by a sick child on a stormy night as the high winds sucked the tent in and out, despite it being tied to our car and nearby trees high in the Rimutakas.

Amazing people became instant friends. This included a police officer from Chicago camping in the West Coast wilderness just days after shooting a man during a violent robbery. We sat with him in the silence, trout disturbing the lake surface as curious native birds flew around us. We visited Havelock where Ernest Rutherford attended school, and made a mercy dash for medical help to treat a child covered in mosquito bites. Camping was fun, hard work, rewarding and cathartic. It offered my family a window into the extraordinary remoteness of this beautiful country.

|

Tolaga Bay

|

Gisborne

|