PERU—Steps in Life by Shirley Read-Jahn

When my older sister, Pam, had a major, round-figure birthday, she always tried to celebrate it by doing something different and memorable. For her 60th birthday in September 2002, she decided she'd like to hike the Inca Trail in Peru. She invited me and our oldest friend, Rowan, who then contacted her neighbour, Liz, in England, a female farmer living near Rowan in England.

That was Pam’s reason for this adventure. For my part, I was a divorced woman, had met somebody new, and needed to get away from work and think about whether to accept his proposal of marriage. Climbing up thousands of huge rocky steps to see the ancient Inca fortress of Machu Picchu would also be an enormous physical challenge for me at 58 years of age and with a chronic health issue. Remarrying would mean another huge change in my life, involving leaving San Francisco to start life with yet another husband.

Pam flew from Sydney to San Francisco to collect me. We met up with Rowan and Liz in Lima for a few days there before flying to Cusco. A highlight for me was going to Lima's Gold Museum. It is filled with gold artifacts and weapons donated to the museum by Miguel Mujica Gallo, a Peruvian diplomat and politician, and it’s where you can see many gorgeously dazzling examples of the last pieces of the Inca Emperor Atahualpa's golden treasures that people refer to as "the lost treasure of the Inca." There are quite a few legends about the lost treasure. The one I like best is that there was a huge shipment of both silver and gold on its way to the Spanish as a ransom for them to release Atahualpa. When the people learned their ruler had been murdered, the Inca General Rumiñahui, in charge of carrying the treasure from Quito in Ecuador for the ransom, had it all thrown into a lake so the Spaniards wouldn't get it. Thus, some people now say many of the artifacts in the Gold Museum are fake, and that this lost treasure is yet to be discovered.

After Lima, we flew to Cusco. Cusco is more than 11,000 feet (3,353 metres) above sea level, situated deep in the Andes range of mountains, and apparently one of the most dangerous airports for a pilot to fly into. I can understand that claim for, as you fly into the ancient city, you're skirting mountains quite close to your wings on either side as you come down into the valley. I remember holding my breath as I looked out the windows as we flew in.

We'd decided to hike with porters carrying our luggage, leaving us to carry only our day pack. We knew that was going to be heavy enough as we climbed up to Machu Picchu. Weight on your back always seems to get heavier as you climb higher. This guided tour was called a luxury hike because we were also to have a cook travel with us all the way. The guides were to set up and break down our nightly camps, put up a toilet tent for us, and the whole trip was to take four days.

Arriving in Cusco we had some time to see the town and become accustomed to the altitude over two days. Our guide told us to drink mate de coca tea and to lie on our backs on our hotel beds with our feet held up high against the wall. This odd trick worked.

Duly acclimatised, we entered the Sacred Valley of the Incas in our guide's vehicle and visited the traditional market town of Pisac and the fascinating Inca fortress at Ollantaytambo. It was there that we were fitted out with the correct length of a bamboo hiking pole each—Pam and I both managed to bring our poles all the way back home after the trip as a cherished possession and memory. The top of each pole is wrapped in llama wool and is colourfully stunning.

In the Pisac market I felt a hand slip into the pocket of my trousers, and quickly slapped it away. It was a female thief, but all she scored was the all-important toilet paper I kept in there. Pam wasn't so lucky. Her handbag strap was speedily cut from her shoulder and the bag stolen.

It is in the high-altitude Sacred Valley of the Incas that up to 4,000 varieties of colourful potatoes are grown, from red and purple to creamy white. The native Quechua people have been cultivating and improving potatoes in this huge valley for seven thousand years. It's now called The Potato Park of Peru.

Before leaving Cusco, we went to see Sacsayhuaman. This is a large, rather rambling fortress-temple complex translating from the Quechua to "Royal Eagle." Our guide told us how to pronounce the fortress’s name is by saying “sexy woman.” We also visited the Cuy Palace, which hundreds of guineapigs have created as a warren for their homes. Cuy is the traditional meat of the area. On our last evening in Cusco before setting off on the Inca Trail, we had dinner at a small restaurant. Other guests were eating cuy but I couldn't bring myself to try it, having bred hamsters as pets, so similar to guineapigs. To my utter amazement, into our hole-in-the-wall restaurant walked one of San Francisco's supervisors, Aaron Peskin, with his wife. I'd done some work fundraising for him some time before, so it felt extraordinary to run into him in Cusco. He'd just returned from hiking the Inca Trail, in continuous rain, with no porters or cook. Talk about making life difficult for oneself.

The following day, over breakfast in Piscacucho on the first day of our Inca Trail hike, our guide told us the village is referred to as KM. 82 (being the starting point on the map for this trail), that we'd be walking 6.8 miles (10.9 km.) on Day 1, and that the whole trail is a little over 28 miles (45 km.) from KM. 82 to the finish—when you enter Machu Picchu through the Sun Gate. With any luck, he said we'd see the sun rise through the gate as dawn began. He warned us that we were the oldest women to have attempted the Inca Trail up to then, thus we would progress slowly but steadily and if we did that, he felt sure we wouldn't need the oxygen tanks some of the porters would be carrying. This was to turn out correct. Younger hikers rushed past us over the four days, but we, rather like the story of The Tortoise and the Hare, ended up plodding past the youngsters, now lying or sitting on the trail, and having to use oxygen. Our guide cleverly placed us four women in a certain order. He put Pam as the leader for it was her 60th birthday trip, and she was doubtless the keenest. I was to follow her, since I was her younger sister and tended to follow her in many things in life. Next came Rowan, followed by the chattiest one, Liz. He said he noticed Liz liked to talk, so she could bring up the rear, and call out to us when other hikers were coming up behind us, needing to overtake us on the narrow paths or steps. That plan worked perfectly.

A 28-mile hike doesn't sound that onerous, but you need to consider the altitude, how steep many of the inclines and the descents are, and, in particular, all those hundreds and hundreds of steep Inca steps to haul yourself up and down on. It’s said that there are nearly 71,000 of these steps from the start of the Inca Trail at KM.82 all the way up to the entry of Machu Picchu itself. I soon realised my bamboo pole was of huge importance and not just for people older than me, or for traditional Tyrolean hikers.

We set off, following our porters who'd dashed ahead, many wearing only sandals looking as if they were created from old tyres. We marched enthusiastically along a dirt path passing a few rural houses and tiny farms. Locals were seated at the side of the path selling plastic bottles of water. I speak fluent Spanish, but it was interesting to me to hear the path-side women, in their traditional colourful skirts and hats, speaking their local dialect of Quechua. They did speak Spanish, too, but with a completely different accent from the Lima Peruvians, and, obviously, different from the castellano puro Spanish I was used to hearing when living in Spain in the mid-sixties.

The first Inca ruin we came upon was the crumbling site of Llactapata, which we looked down upon from a hill we were walking up. It was quite exciting to see our first actual Inca Trail ruin.

Making camp, what a joy to find the porters had our tiny sleeping tents, an open-air toilet tent over a pit already set up, with aromas of dinner emanating from our travelling cook's tent. Knowing it was Pam's 60th birthday, the clever cook had created a cake of layers of pancakes, and stuck candles in the top. It was very kind of her, and quite realistic as a cake.

That evening our guide told us there are still stone pathways networking across the once vast Inca empire, which stretched from Quito, Ecuador to Santiago, Chile. These pathways connected military hubs and major sites (now in ruins). The empire's capital was Cusco.

On Day 2 we walked 7.5 miles (12.07 km.) along dirt or ancient stone paths wending through semitropical forest. We were told to look for gorgeous butterflies but only saw a couple. Most of the day was spent climbing upwards. Pam suddenly bolted off like a bat out of hell. I saw her literally sprinting up toward Warmiwañusca (Dead Woman's Pass), 13,830 feet (4,215 metres) above sea level. The rest of us stopped, shielding our eyes in the bright light, to watch her reach the high pass, where she stood, a tiny figure waving at us, arms upstretched in triumph, with llamas appearing in and out of the swirling mist behind her. The rest of us toiled uphill to join Pam, then all took up our positions in line again, to climb down from Warmiwañusca mountain on those tall, deep stone steps to reach our welcome campsite.

Day 3 was a 10-mile hike (16.09 km.) made up of steep ascents and sharp descents. This mountain's altitude wasn't as high as the first one, which was a relief. We stopped to inspect the round ruins of Runkur Racay, had lunch by a dry lake, then left the track a bit to see Sayacmarca and Phuyupatamarca, looking down into a valley, then Intipata with its massive terraces. Resting here, our guide told us how a true Quechuan man must steal a feather from a condor to prove he's a man. As our group’s interpreter, he gave me a condor feather, which I treasure. This was also the day when we walked across a causeway and through the cloud forest and on through an Inca tunnel carved right through the mountain, two miles long (3.2 km.). It's mind- boggling to imagine how this tunnel was carved so long ago, all by hand. That night we camped at Wiñay Wayna, feeling very sweaty and dirty by now, and much in need of a shower.

Our camp at Wiñay Wayna

Day 4 was "only" 4 miles (6.4 km.) but involved a great number of stone steps to clamber over, both up and down, including 50 steep steps which were almost at a one-in-one angle.

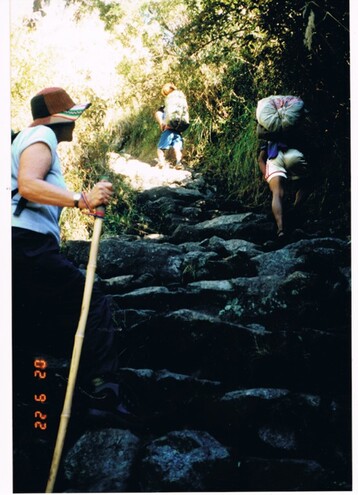

Climbing up an incredibly steep stone staircase

We'd been awakened before dawn by our guide to gain a start on the "Machu Picchu checkpoint" through the Sun Gate. We'd so hoped to see Machu Picchu illuminated by the dawn's rising sun, but no, the complex flickered into view through the Sun Gate, then tantalizingly disappeared again, as the clouds came and went around it.

We continued along the Inca Trail through a mysterious cloud forest and here were lucky to see beautiful butterflies and plants. Along the way, when walking on a path pressed up close to the side of a mountain, with a sheer drop down in places, an electrical storm was suddenly, scarily, upon us. The crashing of the dry thunder and the speed of the zig-zagging lightning bolts shooting around us was terrifying. I clutched my sister, Pam, almost jumping into her lap, and hoping we wouldn't be hit. While crouching on the Trail, I tried to think happy thoughts, tried envisioning a new life in California with a new husband. In hindsight, the thunder and lightning could have been a presage of my new life to come!

Just after the storm passed

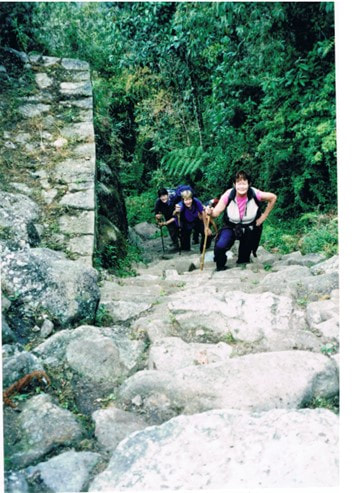

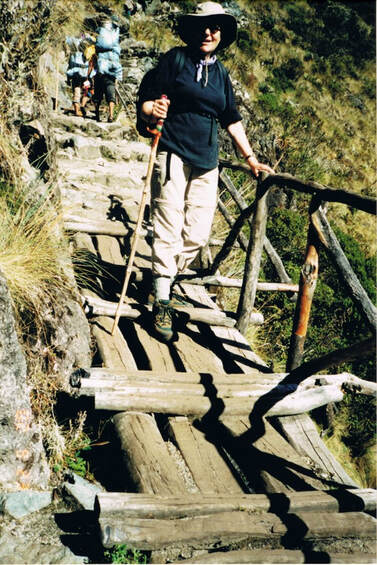

The noisy storm passed over and the dark clouds disappeared, but another hazard approached, at least for Rowan. We weren’t allowed to cross an old Inca bridge made of two tree trunks. That particular bridge is scarily narrow, filling the 19.6 foot gap (6 metres) left in that section of the cliff edge. There’s a 1,900 foot (574 m.) drop below it. It used to be a rope bridge connecting the stone path, used by the Inca army as a secret entrance to Machu Picchu. The bridge we were permitted to cross was smaller. It was suddenly in front of us, appearing and disappearing in mist and clouds. We could barely see a foot in front of us, but it did have one handrail. Rowan suffered from vertigo and refused to cross the bridge. After her tears and our encouragement, eventually she agreed to let our guide cross the bridge in front of her, with him walking backwards, while she followed him, clutching his hands. I walked closely behind her, gently steering her across. We made it safely to the other side, all breathing a huge sigh of relief—especially Rowan.

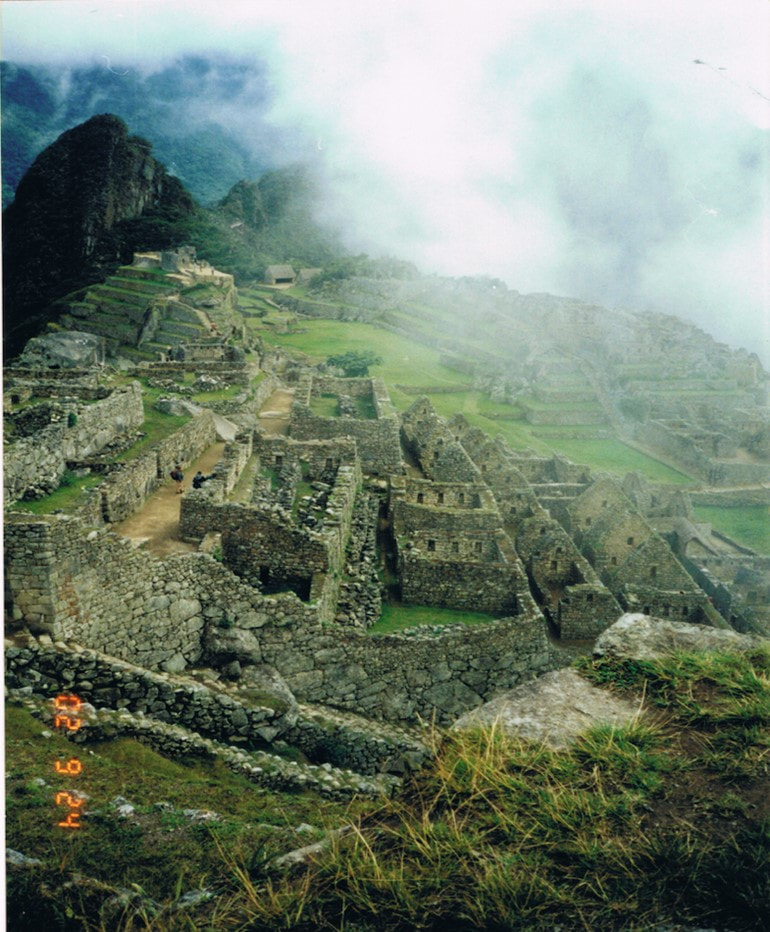

Now walking with more energy, with the carrot of the actual fortress of Machu Picchu before us, we hurried on faster than ever before. Stopping atop the last raised area, we took photos of all of us with the ancient ruins now appearing clearly behind and below us. We spent some fascinating hours touring the ruins of this citadel, 7,782 feet (2,400 metres) up in the Andes. However many photos I'd previously seen of Machu Picchu in the past couldn't do justice to the extraordinarily spectacular ancient stronghold. As my gaze swept over the whole magnificent site, I felt humbled and awed by the Incas' achievement.

The Inca fortress of Machu Picchu, the end

of the Inca Trail

of the Inca Trail

Liz, Pam, Shirley, Rowan at Machu Picchu

Our porters at Machu Picchu

As I stared at the entire scene, I was shocked to see the ancient granite Intihuatana sundial altar had a jutting corner edge completely chipped off. I learned that this horrifying damage occurred when the American advertising company, J. Walter Thompson, was filming an ad for the Peruvian Cusqueña beer company for its Cervesur beer, and its 1,000-pound camera crane operator made a serious misjudgement, letting the crane fall. The granite block had been carved by the Incas centuries before into the mountain. The camera crane operator was sentenced to six years in prison for damaging a world heritage site.

We sadly dragged ourselves away to take the bus down the mountain to the village of Aguas Calientes. A jokester set off running when our bus did and had great fun appearing on the road ahead of us to wave at our bus in greeting. He was obviously tearing straight down while our bus had to zig zag, hence the child was gleefully grinning from ear to ear as we in the bus looked gobsmacked to see his laughing face appearing ahead of us every so often at the bends in the road. Naturally, as we disembarked from the bus, he was right there smilingly asking for tips.

The village of Aguas Calientes (meaning Hot Waters) has a market set up on either side of the train lines which bring a train in and out at regular intervals. The stallholders move their wares back from the oncoming train also at regular intervals. They were masters at speedily erecting then breaking down their stalls, and it was mesmerising to watch. We spent that night of Day 4 in an Aguas Calientes little hotel, to have a welcome shower and a good night's sleep.

The next day we took the little train back to Cusco. It, too, zig zagged all the way down the mountain, having at times to shunt forwards then backwards to make it around the tricky steep bends. I spent much of the train journey staring out the window, pondering on my future, to the rhythmic jerking of the old train as it clanked its way down the mountain. Should I re-marry, should I re-marry, should I re-marry? Would I attain new heights if I took this step of yet another attempt at married life, as much as I now felt elevated both physically and spiritually by climbing all the way to Machu Picchu? I’d already changed my life by proving to myself that I had the courage to climb those 71,000 steps in four days. I could do anything! I’d remarry and surely it would be third time lucky? A smile crept across my face as I thought of all the upcoming changes. A new husband, a new home, a new area to explore…yes, I’d do it! A whole new life before me…