Gormless? by Ronald Mackay

“Ronald, Neil is new. He’ll make up the 8th member of the Swifts.” Ken walked away. He turned back and said quietly, “Keep an eye out for him.”

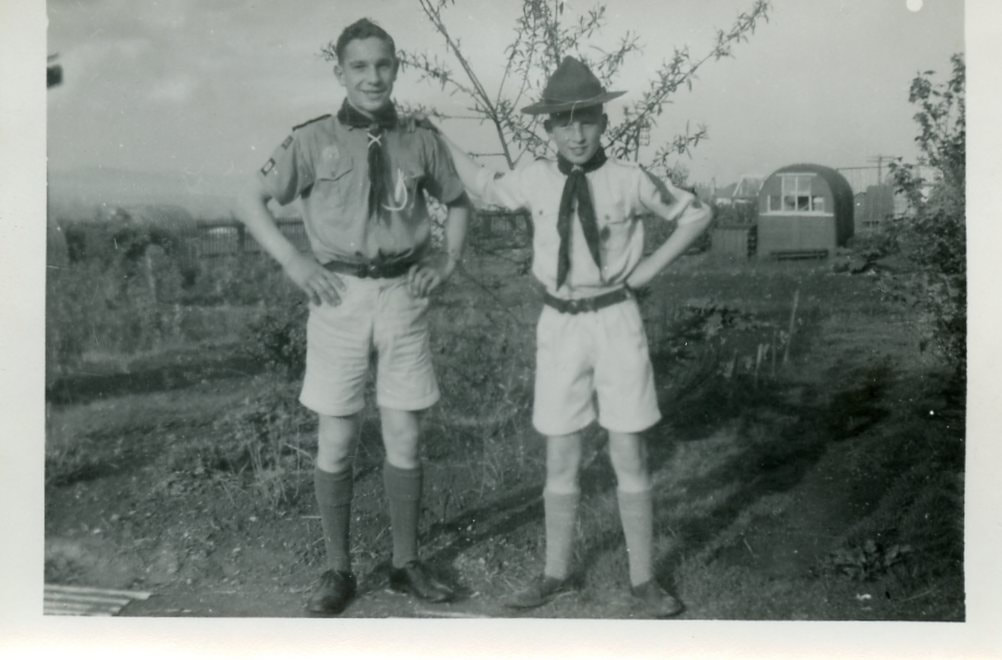

First, I and then my ‘Second’, followed by the remaining five, shook Neil’s hand. Not without misgivings. Neil was a frail-looking thirteen-year-old whose tentative half-smile matched his handshake.

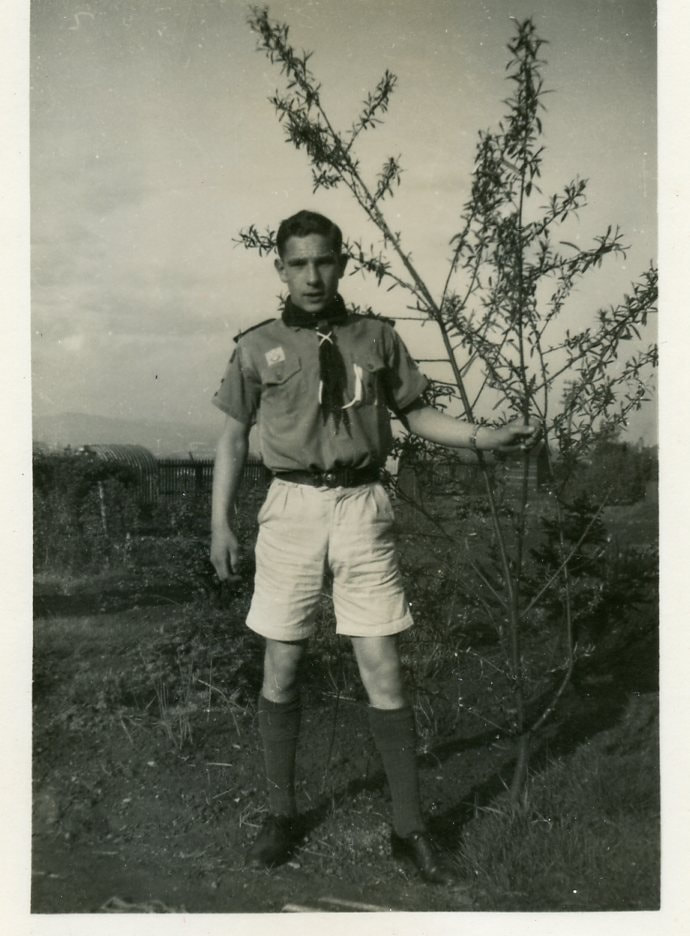

I was a newish Patrol Leader. ‘PL’ of the ‘Swifts’, 54th Boy Scout Troop, Dundee, Scotland. Conscious of the honour, I’d accepted my role with appropriate earnestness. At 15, it was something to have been selected by our Scoutmaster as one deemed capable of taking charge of other young teenaged Scouts, albeit with the support of a ‘Second’. Part of a PL’s task was to spot, encourage and nurture the natural qualities of each of his Patrol members. To build on their strengths and reinforce their weaknesses; to invigorate, support and develop their characters. The goal was to encourage the natural talents of the individual members of his patrol and thereby mould them into a coherent team, capable of showing a common initiative and holding its own in competition. To do so successfully, I was learning, involved quiet observation and intimate knowledge of each individual member of my Patrol.

Neil’s lack of spirit was not lost on me, my Second, nor on my other Swifts. It introduced an unexpected weakness into the Patrol that, together, we would have to overcome if we were to continue to match the Larks, the Curlews, the Crows and the Kittiwakes. It meant that I had to be extra alert and provide special encouragement and support. Without putting the challenge explicitly into words, we all knew that with Neil aboard, we would have our work cut out for us.

***

Summer passed into autumn.

Impeccably uniformed, we Swifts stood at ease in a strict line waiting for inspection alongside the other four patrols. Our turn came. I gave the order.

“Swifts! Atten-shun!” And to our Scoutmaster: “Ready for inspection, Sir!”

As PL, it was my duty to ensure that the members of my patrol were correctly groomed and uniformed. Polished shoes; long socks with green flashes showing beneath doubled-over tops; kilt or khaki shorts, khaki shirt with brightly coloured earned badges; tartan neckerchief, toggle and lanyard in place; and the distinctive wide-brimmed khaki hat set soberly on the head.

Ken, our Scoutmaster, surveyed the Swifts, noted the straightness of our line, the conforming uniforms. He nodded. So began the ritual. Each of us, starting with the Second at the far end and ending with me as the Patrol Leader at the other. Well-practised, in turn we held our hands out. Palms upwards, palms downwards; left knee raised to show it scrubbed clean and the shoe shined, then the right.

Ken stopped at Neil.

“What’s that?” Ken fingered the toggle holding Neil’s neckerchief.

I slid my eyes sideways. He’d been wearing the regulation leather toggle with the fleur-de-lis emblem stamped in gold when I’d made my routine check earlier.

“My toggle…” Neil faltered.

***

I had kept an eye out for Neil; searched with disappointing success for practical endowments to encourage.

From that first evening, I’d discovered that Neil was not like most of the other lads in our Troop. He was diffident, reluctant to engage. He lacked confidence, hesitated to act, and bore a permanently puzzled look on his face as if the world and all in it including his fellow-Swifts, presented an intractable mystery. I had to prod him to participate lest he stand on the side-lines and merely watch. I made sure he wasn’t left behind in the weekly games and exercises designed to teach us the worthy and valuable Scouting skills in our sacred writ – Lieutenant General Robert Baden-Powell’s ‘Scouting for Boys’.

***

“Where did this toggle come from?” Ken raised his eyebrows.

“I made it myself.” Neil made it sound like an apology.

“Where’s your regulation toggle?”

Neil extracted the brown leather band from a pocket in his shorts.

“Put it on!”

Neil switched and placed the offending toggle into Ken’s outstretched hand. Ken raised it aloft, the better to examine it.

There was general laughter. I shushed my Swifts. Ken’s fingers held a homemade toggle woven from strands of bright red plastic wire, the kind used by the girls in the domestic science class to make table-napkin holders while we boys attended workshop.

Neil looked confused.

‘Don’t cry!’ I willed.

“Our 54th Troop,” Ken’s voice was firm but kind, “wears the leather toggle.” He handed Neil back the woven red object. Neil secreted it in his breast pocket and stood there, somehow small, naked and vulnerable. The uneven ends of his re-toggled neckerchief gave him a pitifully lopsided appearance.

Laughter again. This time, Ken silenced the Troop with a withering look.

“Swift Patrol Leader! Show Neil how we adjust our neckerchief.”

Taking advantage of the opportunity to shield Neil from the Troop, I adjusted his neckerchief so that both ends matched in length, all the while, warning with my eyes: ‘Please, do not cry!’. He struggled, but kept tears at bay, saving himself further ignominy.

***

Inevitably, Neil, like most of us, was christened with a nickname. His was not one that suggested mettle or prowess like ‘Crowbar’, ‘Ironman’, or ‘Desperate Dan’ but one that disparaged.

‘Gormless’ was how he was addressed henceforth. A word we Scots used to mean lacking initiative -- and initiative was what we all sought ardently to acquire. It was the Holy Grail that confirmed to us, our parents and to others that we were growing fittingly into adulthood.

***

You see, the episode with the toggle was not an anomaly, merely the culmination of earlier, tiny, teenage trespasses. At first, Neil had cried when he was knocked down during a game, when he was outmanoeuvred by a faster player, when he was unable to prevent a win by the opposing team.

I’d taken him aside. “At our age,” I explained the obvious, “we don’t cry! We’re Boy Scouts. Our motto is ‘Be Prepared’! We must figure things out before they happen so we can take anything in our stride.”

Neil had nodded but I saw he was unconvinced.

After that and much additional coaxing, he’d mastered the tears but would still cower or grimace as if the active and rambunctious Scouting games we engaged in were distasteful. It was as if he failed to appreciate how normal growing boys naturally behaved, tested one another and thereby learned how to cope with whatever life would throw at us. Fox cubs wrestling.

Unlike the other Scouts who, when the evening’s activities were over departed in teasing groups, Neil slipped off secretly, choosing the escape that promised solitude.

***

Concerned, I followed him one evening and noticed his guilty apprehension as I caught him up.

“It looks like we’re heading in the same direction. Where do you live, Neil?”

“Doura Street.”

“Where on Doura Street?”

“Near Stobswell.”

“That’s in the opposite direction.”

He gave me a pleading look that said all. How he purposely avoided the easy route home if it meant being in the company of those whose natural high-spirits appalled him.

***

After that, I regularly took to accompanying Neil to the entrance of the stone tenement where he lived. On those occasions, he would answer questions but volunteer little. He gave me little to work with, to draw him in by.

I always called him ‘Neil’ but for others he had become, ‘Gormless’.

***

One evening as I left him at his tenement, his mother appeared. Neil and she exchanged warm smiles. Anxiety disappeared from his usually troubled face. In her presence, he was the whole person that neither I, nor any of us, had seen before.

“This is my Patrol Leader. Ronald.”

I saluted.

His initiative in introducing me to his mother pleased me. His ‘my Patrol Leader’ touched me. It was true. For the Swifts, I was ‘their’ Patrol Leader just as Ken was ‘my’ Scoutmaster. The Scoutmaster of ‘our’ Troop. The possessive pronoun suggested admiration, respect, even kinship.

For the first time, I became conscious of the responsibility that a ‘my-your’ relationship implied. A relationship where each surrendered trust to the other confident that the trust would not be breached. In that moment, I could feel something for which I lacked the maturity to express in words.

“Go in and get changed.” A mother’s eyes smiled at her son. Content, now, Neil scampered into the darkness and up the stone stairs.

She turned to me. Apprehension had replaced the love that I’d seen in her eyes.

“Thank you!” These simple words were delivered with a depth of feeling only a far-seeing, deeply-concerned mother can summon from her heart.

I knew why she was thanking me and yet I didn’t. She possessed many times my experience of the joys and sorrows, the trials and tribulations that this world delivers. In a troubled home during wartime, some of these misfortunes had extended clutching fingers at me. Now, at fifteen, I was conscious that I was groping at life as if exploring objects in a darkened room with instructions to identify the form and nature of each without knowing what they were or even why the exercise was necessary.

I was conscious of the inevitability of growing up and of the responsibilities that this baffling process incurred. It was a frustratingly obscure game like ‘charades’ played at Christmas parties. A game whose rules callously withheld from the players the details that would illuminate, the precision that would enlighten, the essential essence that would make all clear.

***

“Ronald, there’s something I need to ask you.” Neil’s mother’s eyes were brim-full of concern. Eyes that foretold a sadness beyond my experience or imagination. “Will you have members of your Troop, or at least those in Neil’s -- in your -- Patrol, stop calling Neil ‘Gormless?”

I saw the entreaty in her eyes; heard the supplication in her voice.

“I will.” The promise came out more to unburden her of her anguish than because I believed it was within my power do what she was asking or even to grasp the elusive Why?

***

In the gloaming, I walked home, smelling the sweetness of damp autumn leaves smouldering behind stone walls that protected gardens where branches sagged under the weight of late apples. As I walked, I sought to decipher, untangle, shake out, and grapple with the bewildering whys, the perplexing hows and wherefores of the impulsive pledge I had made and knew I must respect. In some inexplicable way, the plea and the pledge seemed to suggest an elusive metaphor for the direction of life’s proper striving.