In Sweet Rejoicing by Ronald Mackay

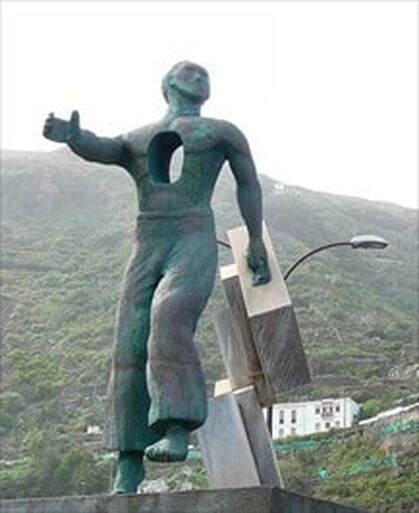

The statue stands on a rock outside the village of Garachico overlooking the Atlantic. A man in vigorous mid-stride, his gaze on the distant Americas, a suitcase clutched in his left hand, a hole where his heart should be.

“That’s Toño, the Emigrant,” Juan pointed. “He represents all Tinerfeños who have left our Islands for the New World.”

Juan lit his pipe and told me this story.

**********

“On his twelfth birthday, Toño started in the banana plantation belonging to the Count, working alongside his father. That’s what boys did, then.

From the steep terraces Toño could enjoy the sight of his tiny village; the fishermen rowing home; the comforting sounds of the carpenter’s saw and the shoemaker’s hammer; the church bells that marked the hours and sanctified the day with prayer.

But the Christmas Toño turned 17, everything changed. At Mass, he approached the Nativity the better to see Baby Jesus in his manger with his smiling eyes and his open arms. And that’s when Toño first saw an angel! Her name was Eva, the youngest daughter of Fausto the shoemaker.

From that day on, Toño never missed Sunday Mass.

After church, young men and women, fresh in Sunday clothes, would stroll in groups around the plaza. They might exchange a few shy words with one another. In those days, that was how courting began, how marriage came about.

Toño and Eva were content with these modest conversations. But Fausto was not. He wanted more for his daughter than a life of drudgery married to a plantation worker.

So, before Toño and Eva could even get to know each other, Fausto took Toño aside.

“Your shoes are worn, Toño. I will repair them, without charge, because I like the look of you.”

As he re-soled the shoes, Fausto asked: “What will you do with your life, Toño?”

“Exactly what I do now. Enjoy our village; the gradual changing of the seasons; my work in the Count’s plantation.” And because Fausto said nothing, Toño felt obliged to add, “I may become foreman when my father retires.”

“In the Americas, a man can earn and become rich.” Fausto winked at Toño. “Then, he can return and marry the girl of his choice.”

Toño heard these as words of encouragement. “Emigrate. Make your fortune. Then come home and marry my angel.”

The wily Fausto knew, however, that once in the Americas, men seldom returned, even more seldom became rich.

“But I have no money for the passage!” Toño felt inadequate.

“Who needs money?” Fausto winked again. “I have connections.”

And that was how Toño secured the promise of his passage to Venezuela even though emigration was illegal in those days and was undertaken in secret.

Eva tried to dissuade Toño. But since they were not engaged – Fausto had acted well before promises could be made – their conversations were oblique and public.

Eva would feign brightness, “Who in our village is not happy with the school they attend or the church they worship in? To love home is as natural as breathing.”

Confused, Toño could only repeat what Fausto had hinted at: “But things can be different.”

“Different?” Eva shook her head. “We love our traditions, and what we love, don’t we want to hold onto forever?”

“The Americas offer opportunities.” Again, Toño repeated Fausto’s words. He paused and looked longingly at Eva hoping she might understand what he felt in his heart. “I will return in two years. Three at most,” he said softly.

During the following Christmas Mass, just as Father Francisco announced the triumphant words: “For unto us is born this day a Saviour,” a stranger touched Toño’s elbow. Toño followed him in silence. From Fausto’s workshop, he collected the cardboard suitcase, left there in readiness for this very secret occasion. On reaching the rock above the harbour, Toño turned and looked back. Eva was standing at the church door, the candles bright behind her. She opened her arms.

The wordless gesture told Toño that Eva loved him and would wait for his return.

From the portico, Eva watched Toño pause, his hand on his heart. Then, as he removed his hand, the setting sun passed clean through him.

Eva blinked once – and Toño was gone.

Now wily old Fausto sprang into action. He encouraged suitable men to woo his youngest daughter but though she had many suitors, she showed no interest. She was steadfast.

But Fausto persisted. In those days, everybody knew that a woman’s life was to marry young, have children, see them marry, and to welcome grandchildren.

In Venezuela, life for Toño was hard. First, he had to pay off the cost of his passage. He cut sugar cane and harvested cocoa, working and saving, clinging to the memory of Eva, his family and his village.

Alone, on his first Christmas, he attended mass in Maracaibo’s cathedral. In the flickering darkness the priest proclaimed, “For unto you is born a Saviour, which is Christ the Lord.” Those familiar, joyful words filled Toño with memories.

The memories drove Toño to work all the harder. He bought a truck and drove it tirelessly between Caracas and the oil refineries of Maracaibo. By the following Christmas, instead of returning home, he bought a second truck, recalling Fausto’s advice to return rich.

Back in Tenerife, Fausto continued to pressure Eva. “Once a man leaves, he forgets.” Relentlessly, he sowed doubt in Eva’s mind just as he had sown ambition in Toño’s.

Time passed. By his third Christmas in Venezuela Toño owned five trucks. He made plans to return to his village and to Eva, but at the very last moment, he bought a sixth truck instead.

Back in Garachico, Fausto’s persistence began to pay off. Eva knew that a woman’s life was to marry, have children, and welcome grandchildren.

So, disappointed by Toño’s growing delays and hounded by her father, she submitted to her woman’s lot. Eva married and welcomed her first child.

Old Fausto made sure that Toño learned that this was so.

To overcome his disappointment and what he told himself was Eva’s betrayal, Toño worked even harder although he no longer knew why. Apart from his trucks, his life had lost its meaning.

More years passed. His fleet prospered and grew.

In Tenerife, Eva had two more children before her husband died. She grew older, stouter, happy enough first with children then with her grandchildren. But there were evenings in the plaza when she could still close her eyes and see Toño as she had seen him on that final Christmas, his arm extended, the setting sun piercing his heart and hers.

Now Toño was tiring of his trucks, of his solitary life in an alien country. He cherished bitter-sweet memories of home, of loss and sadness. His life was no longer supported by a purpose.

On Christmas Eve, as was his custom, Toño attended mass in Maracaibo’s great cathedral.

Listening to the bells tolling in the shadows of the tower and the priest speaking of the miracle that was Christ’s birth, Toño could no longer hold back the tears, the grief of all those years of hardship, exile, betrayal and disappointment.

Toño wept.

All of a sudden, through his silent tears, he saw Eva smiling at him across the manger. Bewildered, he reached towards her but she was swallowed by the crowd of worshippers. Anxious, he followed them into the plaza but Eva had vanished. Toño stood alone, desolate and forsaken.

“Don Antonio!” Father Roberto gently took his arm. “Come!” Toño followed the priest into the sacristy. The old priest sat him down. “Are you in need, my son?”

“I am, Father.”

“What is your need?”

“I need my home.” Toño answered simply. “I need those I left behind in Tenerife.”

“Tenerife?” Father Roberto too, was from the Canary Islands.

“My father and my mother lived there in Garachico all their lives, and their ancestors also. I need to return, Padre, because that village is my home, it is where I left all that I loved.”

In the shaded alcoves of prayer-lapped stone where the fragrance of centuries lingered and the eternity of God’s love dwelled forever, Toño poured out his heart and because Father Roberto understood, he listened without interrupting. Toño told Father Roberto his story from the very beginning. About Eva. Their walks in the plaza. Their unspoken promises one to the other. How Eva had left him. Or was it, perhaps, that he had abandoned her? Father Roberto listened until Toño had finished all that he had to say, all that he had never spoken of before to anyone.

In the candlelight of the silent chapel, Father Roberto spoke.

“One of the tragedies of life lies in the many ways we trespass upon one other, my son. This is why we must learn to forgive. Your regret is robbing you of your present and your future, both. From what I understand, your life came to a halt at the moment of injury and that injury continues to issue a deep pain that is drowning you.”

Toño bowed his head, knowing this to be true.

“You must forgive Eva,” said the priest.

Perplexed, Toño raised his eyes. “Father, I have forgiven Eva. Long ago, she asked for my forgiveness and I gave it.” He turned his tormented eyes on the priest, “I cannot forgive myself, Father; I cannot forgive myself.”

Understanding Toño’s self-imposed suffering, Father Roberto spoke quietly. “Just as you learned to forgive Eva, you can learn to forgive yourself, Don Antonio.”

“But I was intoxicated by my success, Father. I failed Eva. My failure to return to her as I promised is unforgiveable.”

Father Roberto put his hand on Toño’s. “Is not the unforgivable the very thing that we must truly forgive?”

Toño looked at the older man, puzzled.

“Your torment is robbing you of your future. It may be true that each of you broke a promise, unspoken by either of you, but that trespass does not condemn you to live pointless lives. You forgave Eva. Eva accepted your forgiveness and renewed her life. You must now forgive yourself and give it meaning once again.”

“But how, Father? How can I forgive my broken promise?”

“The remedy of forgiveness, my son, is not the forgiveness of an act, it lies in offering forgiveness to the person who acted wrongly. Forgiveness becomes an act of love when it is aimed at a person. You forgave Eva as she forgave you, as two people, one to the other. In the same way you can forgive yourself. You cannot undo the past but you cannot allow it destroy the present and the future.

Father Roberto encouraged Toño to talk further and freely about what he had done badly since he arrived on the shores of Venezuela but also about what good he had accomplished on his journey in this land to which he had come in search of opportunity.

Gradually, as the two Canary Islanders talked, Toño grew in understanding. He learned that all lives have their share of endurance in the face of regret. He came to understand how the act of self-forgiveness would free him from his trespass and allow him regain a love for his own person. He learned that it is never be too late to fulfill a sacred promise.

In the darkness, the two men prayed together. Two simple men who loved these islands and the people among whom both had been born and nurtured.

Home at last in Tenerife, Toño dismissed the taxi before it reached his village. He felt a need to stand alone on the very spot from which, all those long years ago, he had left in secret, promising wordlessly to return.

He smelled the salty Atlantic across which he had twice travelled and felt once more the sweet sense of belonging. The church doors lay open. Eva stood there smiling, the candles bright behind her. She stretched out her arms to him and he to her.

Grey-haired, creased and bowed by the years, the two touched. All of time and both their lives were consummated in that moment.

Toño and Eva walked arm-in-arm into their church. At one with each other, together at last, they listened to the priest. “Thanks be to God who gives us victory through the birth of the Lord Jesus Christ”. In the manger, the Baby Jesus smiled and opened his arms to embrace them both in grace and truth, knowing everything there was to know about each of them."

**********

Juan finished his story and began to refill his pipe. Neither of us spoke. Our silence was broken by the peal of church bells.

“Come, give thanks! Christmas is a festival of gratitude, a time to offer thanks to God whose son guides us through life, brings us consolation in times of darkness, and joy everlasting.”

El Migrante at Garachico Tenerife